Computing Science

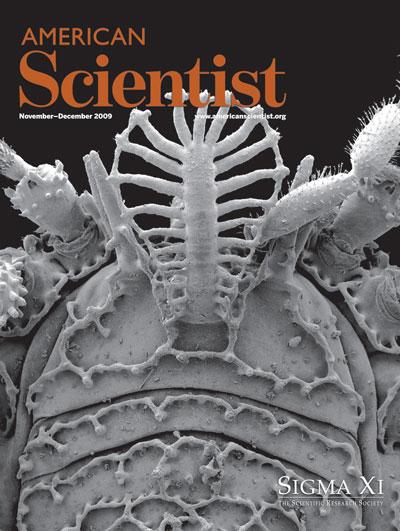

Found in caves and wooded canyons of the Sierra Nevada in California, this Ortholasma harvestman is an unnamed and undescribed new species, less than a centimeter in length. The ornate grillwork over its body, springing like an Elizabethan collar from between its tiny eyes, is an adaptation to gather and hold particles of soil, which probably serve to camouflage it from predators. The brush-like appendage it brandishes is covered in sticky hairs, and may be used like flypaper to gather the small insects and mites on which it feeds. The specimen was cleaned using ultrasonics and photographed by William A. Shear under a scanning electron microscope at East Carolina University. In "Harvestmen," Shear describes more weird wonders from the world of these strange and diverse arachnids.

Opiliones—which include daddy-long-legs—are as exotic as they are familiar

A global travel surge is inevitable, but runaway growth of mobility-related CO2 emissions is not

An analysis of luck versus skill in the epic polar expeditions of Fridtjof Nansen and Sir Ernest Shackleton

Click "American Scientist" to access home page