This Article From Issue

November-December 2009

Volume 97, Number 6

Page 516

DOI: 10.1511/2009.81.516

FRESH POND: The History of a Cambridge Landscape. Jill Sinclair. The MIT Press, $29.95.

Equipped with a supply of good city water, I set out from Cambridge by bicycle one hot August day for a favorite new spot called Lusitania Meadow. This wet meadow, exuberant with wildflowers and cattails, is literally new—a “landscape restoration” on the site of a former soccer field.

While watching a busy pair of goldfinches, I pondered this hypernatural scene with the context supplied by Jill Sinclair’s Fresh Pond: The History of a Cambridge Landscape. Lusitania Meadow is part of the Fresh Pond Reservation, a hardworking and hard-worked piece of the Massachusetts urban landscape. And it is only the latest of many, many makeovers.

From Fresh Pond.

In Fresh Pond, Sinclair shows what can be learned by investigating the environmental and sociocultural history of a patch of land or water profoundly marked by human activity. Our enthusiastic “restorations” of landscapes obscure the marks left by our ancestors. So it is with Fresh Pond, a glacial kettle that over the years has been thoroughly resculpted, its shorelines rebuilt and regraded, its vegetation stripped and replanted, to fit the changing requirements of commerce, public health, recreation and aesthetics.

Peeling back the layers of time, Sinclair reveals the icehouses that once sat near the site of my meadow. In the early 19th century, a pair of young entrepreneurs came up with improved methods of ice harvesting and set about removing ice from Fresh Pond and shipping it to warmer climates. The ice traders cut the ice into large blocks, stored it aboveground in insulated buildings and mechanized the moving of it, and the business took off. By 1841, Fresh Pond had a railroad spur and large icehouses along its shores. (Fresh Pond’s ice traders turned up in Concord, alarming Henry David Thoreau, after the extension of rail service there. Thoreau was pleased that ice from Walden Pond didn’t seem to find a market.)

Toward the end of the century, industrial and urban growth and health concerns created demand for public water sources. The ice merchants were pushed out, and in the 1890s Fresh Pond became a town reservoir, which remains in service, supplying the water I carry there. Bogs were filled in; the lake’s swampy “nooks” were separated from the reservoir and left unfenced, to the delight of today’s dog owners. The current shape of the lake and environs is largely the creation of the Cambridge Water Board and the landscape architects John Charles Olmsted, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and Charles Eliot.

Sinclair regrets that obliteration of the past has kept Fresh Pond off the National Register of Historic Places. My meadow is part of that obliteration, and so I’m grateful for thoughtfully written, well-illustrated histories such as this one and Gaining Ground, Nancy Seasholes’s comprehensive study of land making in Boston (2003, also from the MIT Press). Such scholarship can help us understand better the essential role of the landscape in the human experience.—Rosalind Reid

NO IMPACT MAN: The Adventures of a Guilty Liberal Who Attempts to Save the Planet, and the Discoveries He Makes About Himself and Our Way of Life in the Process. Colin Beavan. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $25.

We’ve all heard by now that individual action can’t solve the environmental problems that threaten to do us in. It’s a discouraging thought: Why bother driving less or eating locally grown food if large-scale change only happens with glacial slowness—and the result is that we end up with no glaciers left?

In No Impact Man, Colin Beavan wrestles with this quandary, and offers one of the only satisfactory answers I’ve heard: Try anyway. Beavan and his wife Michelle, who live in New York City with their young daughter, attempt to make no net environmental impact for one year. They stop producing garbage, turn off their electric power, and get around on stylish and practical cargo tricycles that can carry both their daughter and their groceries.

It would be difficult, in writing about a project like this one, to avoid sounding preachy, but Beavan makes a good go at it, emphasizing that his desire was to change his own behavior, not other people’s, and chronicling his mental struggles with humor. But under the flippant tone is hard fact, and plenty of it—about carbon emissions, water supplies, agriculture, transportation and more—providing solid reasons for taking small actions. I began the book skeptical, sure that Beavan would miss some huge aspect of environmental change, such as the vastly disproportionate effects of environmental problems on the poor. But I was happily proved wrong. And an extensive appendix contains an annotated list of organizations and resources.

Readers will find more of the personal stories that make the book shine at the blog on which Beavan documented his year, http://noimpactman.typepad.com/. I did wish that more of these stories had made it into the book, but that’s about the only thing I wanted after reading No Impact Man.

Although I wouldn’t mind having one of those spiffy cargo tricycles, either.—Anna Lena Phillips

IN SEARCH OF JEFFERSON’S MOOSE: Notes on the State of Cyberspace. David G. Post. Oxford University Press, $27.95.

“I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it.” So wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1791, and Temple University law professor David G. Post believes that the same vision should guide us in governing cyberspace, a world that’s just as expansive, varied and chaotic as Jefferson’s America.

Post’s book In Search of Jefferson’s Moose takes its title from an episode during Jefferson’s tenure as minister to France: In 1787 he had the “complete skeleton, skin & horns” of an American moose mounted in his residence in Paris to remind him of the vast potential of the unexplored New World. Post seeks to apply the ideas of the founding fathers to policy in the online world. How should we govern this “territory”? Who should decide the vexing questions we encounter there regarding free speech, terrorism, property and privacy? And who should decide who should decide?

Post is focused on today’s technological reality, but his well-informed discussions also bring the past to life. Our experience of the untamed Internet illuminates the New World over which the founders struggled, a world of endless exigency, vast opportunity and very little precedent. Such a world, Post argues convincingly, will prosper best under Jefferson’s ideal of community self-governance: Online destinations should make their own law, with as much protection for speech as possible and as little protection for intellectual property as necessary.

Post, although he is persuasive, is not always sure-footed. His analogies can be strained, and his discussions of both history and technology sometimes grow too technical to fit in with the larger metaphor. But his book addresses important questions that we all should be asking, and he acknowledges the scope of his undertaking with a candid humility that would have pleased Jefferson. “If I am not up to the task, so be it,” he writes. “I’m not sure anyone is really up to this task, but one has to start somewhere.”—Greg Ross

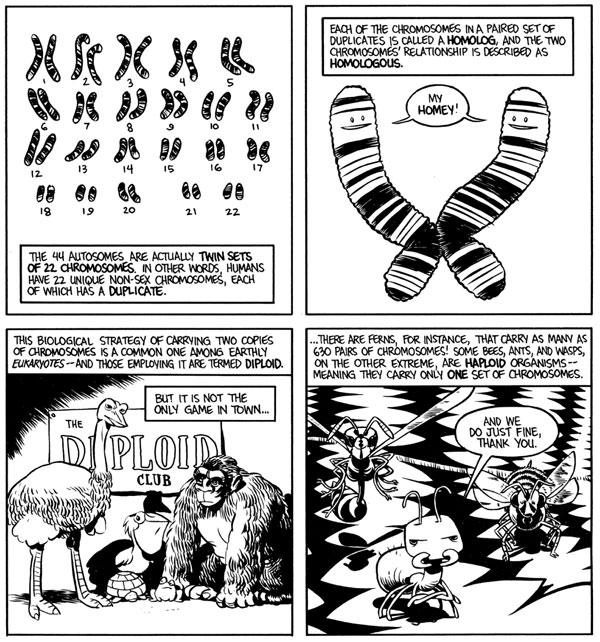

THE STUFF OF LIFE: A Graphic Guide to Genetics and DNA. Mark Schultz. Illustrated by Zander Cannon and Kevin Cannon. Hill and Wang, $14.95.

The Stuff of Life is surely the only book about genetics narrated by an extraterrestrial who looks like a cross between a sea cucumber and a starfish. Bloort 183 has just returned to his home planet after visiting Earth on an important mission: to learn from Earthly biology clues that might save his own species, the Squinch, from a genetic disease. His report to the Squinch about the basic biology he learned from Earthlings is lighthearted, succinct and correct. Author Mark Schultz and illustrators Zander Cannon and Kevin Cannon have done a fine job of weaving technical detail into an amusing story.

From The Stuff of Life.

The first half of the book is devoted to fundamentals such as cell division, gene expression, reproduction and inheritance (Gregor Mendel is a major character). Cells and molecules are given faces and goofy expressions, but they’re also named and explained properly. The glossary, which has more than 100 entries, should have been even larger—many terms mentioned in the text are not included. However, the comic format eases somewhat the burden of keeping the technical nomenclature straight. For example, the cartooning of molecules helps distinguish enzymes from one another. Memorable flourishes include DNA polymerase drawn with a Jimmy Durante schnozz and a ribosome sporting Groucho eyebrows.

The latter half of the book focuses on applications and implications of modern biology, including recombinant DNA, genetically modified organisms, genetic testing, gene therapy and cloning. The book does a particularly nice job integrating the fundamental importance of variation, selection and evolution into discussions of these topics.

The Stuff of Life is rich with information (if only there were an index!), but at 150 pages, it isn’t meant to be a substitute for a mainstream textbook. But it’s a fun and engaging supplement, and biologists will be pleased with its scientific accuracy.—Chris Brodie

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.