Magazine

March-April 2022

March-April 2022

Volume: 110 Number: 2

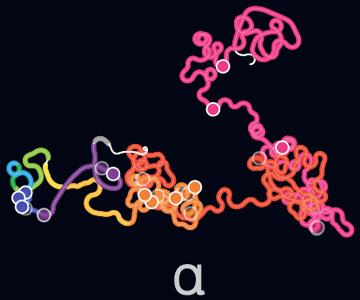

Water fleas (Daphnia cucullata) change shape depending on their environment. Usually, they develop into their common form (bottom row). However, if they sense chemicals given off by predators, they develop into a distinctive, protective form (top row). A water flea that has taken this form has a long, pointed helmet on its head and a spike on its tail, making it difficult for invertebrates to catch and eat it. As it turns out, this ability to change features in response to the environment—a phenomenon known as phenotypic plasticity—occurs in all major groups of organisms, from bacteria to mammals. Its widespread existence raises such vexing questions as: How does such developmental flexibility evolve? Can environmentally induced features be passed on to the individual’s offspring? And does plasticity affect evolution? In “Evolution and the Flexible Organism,” evolutionary biologist David Pfennig addresses these and other questions about this fascinating but often misunderstood phenomenon. (Image by Christian Laforsch/Science Source.)

In This Issue

- Agriculture

- Astronomy

- Biology

- Communications

- Engineering

- Environment

- Ethics

- Evolution

- Mathematics

- Physics

- Policy

- Psychology

- Sociology

- Technology

Operational Oceanography

Naomi Oreskes

Physics

During the Cold War, military funding shaped deep-sea research priorities, which resulted in a new understanding of forces below the water’s surface.

A Curator's Tour Through Fly Collections

Erica McAlister

Biology

At the Natural History Museum, London, the diversity of Diptera specimens is vast and impressive. How are they researched and maintained?