This Article From Issue

January-February 2024

Volume 112, Number 1

Page 12

In this roundup, managing editor Stacey Lutkoski summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief: www.smartbrief.com/sigmaxi/index.jsp

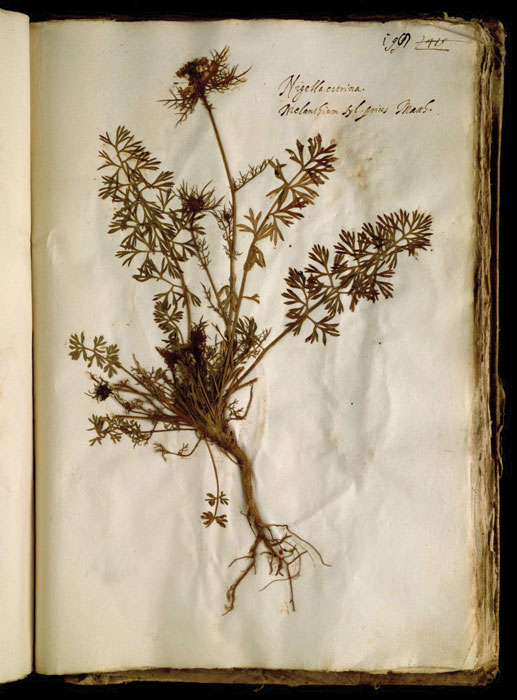

Botanical Time Capsule

Alma Mater Studiorum/Università di Bologna

Researchers are studying a Renaissance herbarium to learn how northern Italian flora has changed over the past 500 years. Sixteenth-century naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi preserved approximately 5,000 dried botanical specimens, which he had collected around his home in Bologna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of northern Italy. His 15-volume herbarium includes notes describing where the plants were collected; some specimens also have information about species abundance, local names, and medicinal uses. This unique herbarium is the world’s oldest-known comprehensive documentation of local flora. Over the centuries, many more botanists have documented the same area, and now a team of botanists from the University of Bologna have analyzed the records to see how the region’s botanical landscape has changed. The researchers compared Aldrovandi’s herbarium to two other sources—Flora della Provincia di Bologna by botanist Girolamo Cocconi (1883), and entries in the Floristic Database of Emilia-Romagna from 1965 to 2021. They found that some species that were common in Aldrovandi’s time are no longer present in the region, and that biodiversity has declined overall. Cocconi wrote his compendium during the Little Ice Age, an extended period of colder-than-average temperatures in Europe. His record included plants that are normally found in colder climates and higher altitudes and which were not found in the other two sources. The researchers found a sharp increase in numbers and varieties of non-native plants over the centuries, particularly those from the Americas. These changes reflect the far-reaching effects of a global economy, which was just beginning when Aldrovandi compiled his collection.

Buldrini, F., et al. Botanical memory: Five centuries of floristic changes revealed by a Renaissance herbarium (Ulisse Aldrovandi, 1551–1586). Royal Society Open Science 10:230866 (November 8, 2023).

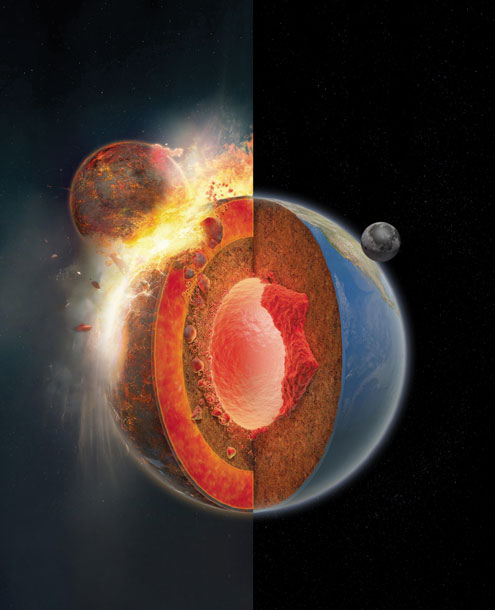

Protoplanet inside Our Planet

Hernán Cañellas

The giant impact that created the Moon didn’t just break off pieces of Earth—it also left chunks of an alien planet behind. The interior of Earth has two continent-sized areas located just above the core that are seismically different from the surrounding mantle, which suggests that they are composed of different and denser material. A team led by geophysicist Qian Yuan at the California Institute of Technology suspects that those anomalous areas are fragments of remnant material from the protoplanet Theia, which is believed to have crashed into Earth 4.5 billion years ago. Their model shows that after the collision, part of Theia’s dense mantle could have merged with Earth, sunk through its interior, and accumulated above the core. This theory solves two mysteries: What are the unexplained seismic anomalies that have been detected in Earth’s deep interior, and what happened to the fragments of Theia that did not become part of the Moon?

Yuan, Q., et al. Moon-forming impactor as a source of Earth’s basal mantle anomalies. Nature 623:95–99 (November 1, 2023).

Menopausal Apes

Courtesy of the Ngogo Chimpanzee Project

Humans are unusual in that they live long past their reproductive years; now it turns out that chimpanzees do as well, and like humans they also experience menopause. The long-studied Ngogo population of Ugandan chimpanzees show clear evidence that females over the age of 50 experience menopause. Researchers led by anthropologist Brian M. Wood of the University of California, Los Angeles, examined 21 years of demographic data for the Ngogo chimpanzees and found that fertility dropped after age 30, and there were no births after age 50. The team also analyzed urine samples from females aged 14 to 67 years old and found that the chimpanzees experienced hormonal changes similar to those in menopausal humans. Menopause is very rare in the animal world—it had previously only been observed in humans and a few species of toothed whales, such as orcas, but never before in apes. The “grandmother hypothesis” suggests that females who live past reproductive age play an important role in raising matrilineal offspring, as has been observed in humans and whales, but that does not seem to be the case with chimpanzees. The postmenopausal chimps do not live with their daughters, who most often leave their natal group once they reach reproductive age, and they typically do not care for unrelated babies. Instead, these findings support an alternative evolutionary explanation: The reproductive conflict hypothesis posits that older females are related to many members of their group and cannot compete with younger females, so the benefit of continued fertility is low.

Wood, B. M., et al. Demographic and hormonal evidence for menopause in wild chimpanzees. Science 382:eadd5473 (October 27, 2023).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.