Magazine

November-December 2002

November-December 2002

Volume: 90 Number: 6

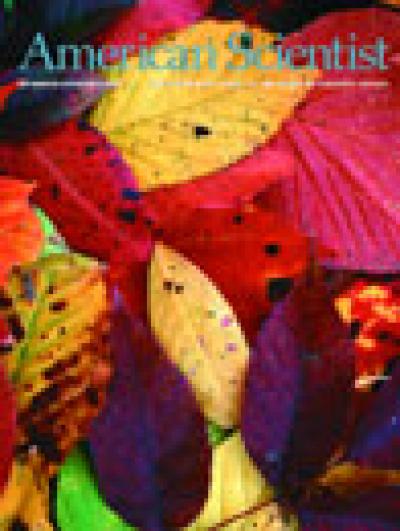

Fallen leaves on a forest floor show the varied autumn colors of trees common in the eastern United States. The yelow leaves get their tint from the loss of chlorophyll, but the red and brown leaves' colors arise from the accumulation of pigments called anthocyanins during senescence. In "Why Leaves Turn Red," David W. Lee and Kevin S. Gould explore the benefits plants might obtain from expending energy to produce an extra pigment in leaves that will soon die. The species in the photograph are: witch hazel, hobble bush, Northern wild-raisin, sugar maple, red maple, ash, black cherry, high bush blueberry, gray birch and beech. (Photograph by David Lee, taken at Harvard Forest in central Massachusetts, mid-October 1998.)

In This Issue

- Art

- Astronomy

- Biology

- Chemistry

- Communications

- Computer

- Engineering

- Environment

- Evolution

- Mathematics

- Medicine

- Physics

- Policy

- Psychology

- Sociology

- Technology

Why Leaves Turn Red

David W. Lee, Kevin Gould

Biology Chemistry Evolution

Pigments called anthocyanins probably protect leaves from light damage by direct shielding and by scavenging free radicals

Science as Theater

Kirsten Shepherd-Barr, Harry Lustig

Art Biology Communications Physics Sociology

From physics to biology, science is offering playwrights innovative ways of exploring the intersections of science, history, art and modern life

Magnetic Resonance Imaging with Polarized Gases

Stephen Kadlecek

Medicine Physics Technology

Although conventional MRI cannot track inhaled or dissolved gases in the body, physicians may soon be able to do so using specially prepared atoms

The Origin of the Solar Wind

Richard Woo, Shadia Habbal

Astronomy

A novel way of looking at the solar corona reveals a hidden "imprint" of the Sun