This Article From Issue

July-August 1999

Volume 87, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/1999.30.0

The Birth of the Cell. Henry Harris. 288 pp. Yale University Press, 1999. $30.

What is a cell? From introductory biology class I remember a list of characteristics that all cells have in common: a membrane, genetic material and the ability to reproduce. It is through the search for, and the discovery and characterization of, these three conserved properties that Sir Henry Harris tells his story, The Birth of the Cell.

Harris weaves a most interesting tale, from Leeuwenhoek and Hooke in the 17th century through the earliest days of the 20th century. This book is foremost a narrative full of political intrigue, professional jealousy and binary fission. A second defining character of the book is its attempt to determine precedence for the most important discoveries (basic structure, the cell theory, cell duplication, nuclear inheritance and so on).

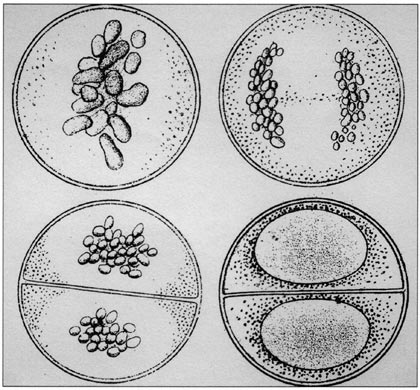

From The Birth of the Cell.

Harris spends a good deal of time clarifying the contributions of Jan Evangelista Purkyne. My familiarity with Purkyne had ended at the "Purkinje cell" of the cerebellum. (Purkinje is the German spelling of Purkyne's Czech name, Harris informs us.) Harris examines the breadth of Purkyne's work and the politics that may lie behind his inadequate reputation. Beyond identifying the ganglion cells of the cerebellum, Purkyne and his students coined the term "germinal vesicle," identified cells with nuclei in human skin, described a technique for cutting sections of decalcified bone, discovered ciliary movement in mammalian cells and much more. However, Harris focuses on Purkyne's argument that all solid animal tissues were composed of cells and fibers and that the cells of animals were homologous with the cells of plants. Such a simple statement to make now, yet someone had to be the first to state it clearly. Unfortunately, it appears that the credit goes to Schleiden and Schwann, whose names are indelibly linked to the cell theory. The theory of Schleiden and Schwann appears more wrong than right, which by itself is not unusual. But it is also less deserving of attention when the contributions of Purkyne are taken into account.

From a practical point, Harris has done more than narrate the story of cell discovery: He has produced a reference that allows students of history to make up their own minds. A reader will come across several passages where Harris disagrees with another author's interpretation of a long-dead scientist's data. Although one could question his choice of quotations, his inclusion of relevant pieces in their original language (also translated into English) does allow an immediate reading for clarification if one so wishes and is able.

Perhaps the only disappointment, and a minor one, is the paucity of scientific images. Whereas we see sketches or photos of nearly every scientist named in the book (52 by my count), only 16 plates appear with original illustrations. It would have been interesting to place more visual examples of what these microscopists were seeing.

The Birth of the Cell begins when humankind had only the most rudimentry hypotheses that cells existed. By the end, the reader has taken one large step after another through the process of cell discovery. The book ends in the early 19th century, when the theory that all living creatures are composed of homologous cells was widely accepted. Along the way, Harris clarifies who truly deserves credit for discovering what. This book deserves to be read by anyone with an interest in history or the cell.—Robert E. Peterson, Zoology, Duke University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.