This Article From Issue

November-December 2019

Volume 107, Number 6

Page 330

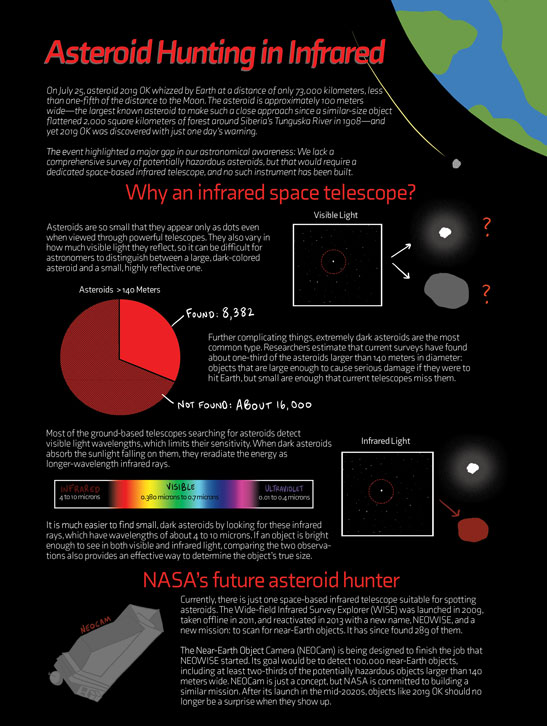

On July 25, asteroid 2019 OK whizzed by Earth at a distance of only 73,000 kilometers, less than one-fifth of the distance to the Moon. The asteroid is approximately 100 meters wide—the largest known asteroid to make such a close approach since a similar-size object flattened 2,000 square kilometers of forest around Siberia’s Tunguska River in 1908—and yet 2019 OK was discovered with just one day’s warning.

The event highlighted a major gap in our astronomical awareness: We lack a comprehensive survey of potentially hazardous asteroids, but that would require a dedicated space-based infrared telescope, and no such instrument has been built.

JoAnna Wendel

Why an infrared space telescope?

Asteroids are so small that they appear only as dots even when viewed through powerful telescopes. They also vary in how much visible light they reflect, so it can be difficult for astronomers to distinguish between a large, dark-colored asteroid and a small, highly reflective one.

Further complicating things, extremely dark asteroids are the most common type. Researchers estimate that current surveys have found about one-third of the asteroids larger than 140 meters in diameter: objects that are large enough to cause serious damage if they were to hit Earth, but are small enough that current telescopes miss them.

Most of the ground-based telescopes searching for asteroids detect visible light wavelengths, which limits their sensitivity. When dark asteroids absorb the sunlight falling on them, they reradiate the energy as longer-wavelength infrared rays.

It is much easier to find small, dark asteroids by looking for these infrared rays, which have wavelengths of about 4 to 10 microns. If an object is bright enough to see in both visible and infrared light, comparing the two observations also provides an effective way to determine the object’s true size.

NASA's future asteroid hunter

Currently, there is just one space-based infrared telescope suitable for spotting asteroids. The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) was launched in 2009, taken offline in 2011, and reactivated in 2013 with a new name, NEOWISE, and a new mission: to scan for near-Earth objects. It has since found 290 of them.

The Near-Earth Object Camera (NEOCam) is designed to detect 100,000 near-Earth objects, including at least two-thirds of the potentially hazardous objects larger than 140 meters wide. NEOCam is just a concept, but NASA recently committed to building a similar mission. After its launch in the mid-2020s, objects like 2019 OK should no longer be a surprise when they show up.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.