3D Printing Medical Devices

By Fenella Saunders

First Person: Joseph DeSimone

First Person: Joseph DeSimone

Joseph DeSimone is a chemist by training who started out specializing in polymers, looking at ways to make them more environmentally sustainable. He has since gained recognition for his work on 3D printing technologies, and he also focuses on applications of polymer technology in medical fields. DeSimone has worked on polymers as small as nanoparticles and as large as automotive parts, and for fields as divergent as nanomedicine and battery technology. He is currently the Sanjiv Sam Gambhir Professor of Translational Medicine and Chemical Engineering at Stanford University. In 2016, he was awarded the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, and he was the recipient of the 2018 National Academy of Sciences’ Raymond and Beverly Sackler Prize in Convergence Research. DeSimone spoke with American Scientist Editor-in-Chief Fenella Saunders about his research. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Courtesy of Stanford University

What got you interested in connecting 3D printing to medicine?

My connection with medicine is the second half of my career. I started out as a polymer scientist trained at Virginia Tech. When I got to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a colleague in the medical school who was interested in gene therapy and delivering nucleic acids contacted me. I didn’t know anything about that area. DNA was a lovely polymer, I thought.

I started looking at the literature about how people were doing gene therapy, and they were basically delivering genes with simple molecules that were similar to paint. Here is the most beautiful molecule I’ve ever seen, and it was being delivered with paint. There was such a gap in the intellectual significance of that. And so we started getting into top-down manufacturing, using the lithographic tools out of the computer industry. We started using the 2D molding technologies that were enabled by lithography to make precision particles for medicine.

It became clear that as excited as I was about the field, the lithographic technologies were very limited. Molding has its symmetry challenges, so you can’t have complex geometries. I began thinking more and more about making things with patterned light in three dimensions, which is the foundation of 3D printing. We needed to figure out how to use light and get a great material.

Some of the best polymers are made by reactive liquids. Think about an epoxy glue: Two substances are kept separate until they are combined to react, and then they react quickly. Nobody in 3D printing went down into that space, because the printers were too slow. We had a hot time window to work in. But those reactive liquids are not UV-curable; they were just reactive. We combined the two properties, UV curability and reactivity, a combination that is referred to as dual cure. That process opened up the materials space, from epoxies to polyureas to polyurethane, to silicone and cyanate esters. And those materials offered us a platform that allowed us to scale up.

We moved into probably the most impactful area that I’ve been involved in, and maybe it sounds a little mundane, but it’s in the dental field. We brought out the world’s first FDA-approved 3D-printed dentures. There are 30 million Americans who can’t afford dentures. This is a $14 billion industry. It’s hard to get a job if you don’t have your teeth. You can’t eat properly or speak properly. There are a lot of dentureless people out there.

With the 3D-printed dentures, rather than eight chairside visits and a handcrafted, molded product, patients have a digital scan of their mouth and two chairside visits. We heard a lot of challenging personal stories, such as somebody whose mother had Parkinson’s disease and struggled to sit in the chair for eight visits. Then, if she lost the dentures, she had to get back in that chair. If you lose our 3D-printed dentures, you just order a new four-pack. They’re digitally reproduced, and they’re perfectly fitting.

You can really transform people’s lives. We’ve set up a nonprofit in Durham, North Carolina, called Local Start with the UNC dental school to provide people who can’t afford dentures with access, considering the upward mobility side of the equation. It is really impactful in the health care space. That process brings together software, hardware, materials science, business models, partnerships—an amazing set of things.

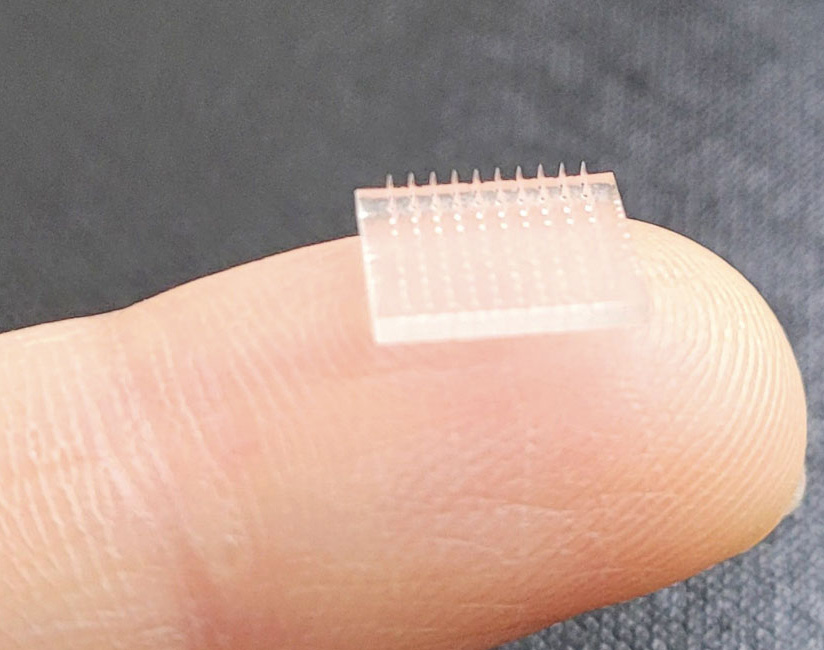

Now we’ve built a printer with a pixel size of 1.5 microns—remember a red blood cell is about 8 microns in diameter, so we’re making really small things—and we’re making microneedles for the delivery of vaccines transdermally. Vaccines target the migratory immune cells in our body. But the vaccines are injected into our muscle, because that’s a convenient way to dump a bolus of liquid with minimum pain and in a reproducible way. But we have 100 to 1,000 times more migratory immune cells in the dermis of our skin than we do in our muscle. When we deliver the same vaccine in the same amount and the same type, but into the dermis through pain-free microneedles, we see a 50-fold increase in antibody response in a preclinical animal model, simply because that’s where the target immune cells are. And through a microneedle, the vaccine is given in a dry state, encapsulated in sugar instead of in water, so array patches could be mailed to people without a cold supply chain.

Courtesy of Joseph DeSimone

To me, this is the ultimate in convergence. We’re deep in immunology. We’re deep in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. We’re deep in materials science. We’re deep in 3D printing. We’re deep in understanding policy. I’m excited about the opportunities for digitally printed structures. We’re iterating designs that you can’t make any other way to make 3D printing microarray patches as reliable as a needle and syringe into the muscle.

Microneedle research has been going on for some time, so why are they still not the pervasive method for vaccinations?

Microneedles were developed in the 1970s. They were fabricated using the tools of the microelectronics industry in the beginning, etched in silicon and metal. It’s very difficult to have different structures on the silicon and metal wafer, or even different heights, which results in a bed-of-nails effect. Because the needles are all the same height, they require a lot of force to insert them. And the materials were very limited. I call that microneedles 1.0.

Microneedles 2.0 involved making a mold of the microneedles etched in silicon, and molding replicas of those out of different materials. It opened up the materials space. But you still had the shape limitations, and now you had fidelity of replication issues. You could make a much sharper edge in silicon than you could by molding the microneedles out of an elastomer. You also tied the mechanical properties of the needle to the excipients that you were molding, because the needle is what gets delivered into the skin.

I call the advent of high-resolution 3D printing microneedles 3.0. The needles are directly fabricated out of a wide range of materials into designs that are unmoldable. We’re now making microneedles that are latticed, and needles of different heights to get access to different layers of skin, to avoid the bed-of-nails effect. We have, at a patch level, needles that stretch the skin, so you have reproducible delivery.

Microneedles have not become a go-to technology because their effects have not been reproducible. A syringe needle with all the liquid dumped into a bolus deep in the muscle is absolutely reproducible. It’s going to take—at a needle level and a patch level—new designs to make the patch reliable and reproducible. I think that’s what has held back the whole field.

How does the method you are using differ from other types of 3D printing?

There are four different classes of polymer-based 3D printing. There is extrusion technology, like a hot melt glue gun. There’s a powder sintering technology: A laser hits a layer of powder, and the powder sinters in adjacency, both bottom and top, to create an object. There’s a jetting technology, where jets of material are added. And then there’s what we call vat polymerization, which uses liquid resins that are curable with ultraviolet light. We’re doing a cousin to that.

The technology has always been rooted in the lithographic world. Basically, you have a platform coming down to a window that sandwiches a layer of UV-curable resin, and you project a pattern. You cure that resin and glue the platform onto the window. That’s a layer. The question is, how do you do the next layer. Well, you have to fracture it off the window, create a gap, recoat with new resin, reposition, and do it again. Then that’s a new layer. It’s like 2D printing over and over again.

We were interested in how we could project an image from underneath into a liquid puddle, but have the image be above the window, so that we would have a gap. Our first idea was a focal plane above the window. That turned out to be a bad idea, because you still have light coming through the window, which would cure the resin. So how do we maintain light coming through without curing? With oxygen, which acts as a polymerization inhibitor. Anybody that free-radically cures any monomer, the first thing they do is degas it. You get rid of the inhibitor, the oxygen. We thought, “What if the window would replenish the oxygen that the light was consuming, and do it in a spatially combined way?”

We ended up designing a window that was chemically robust, optically transparent, and the most oxygen-permeable material on the planet, so that the part wouldn’t cure at the window. We had a mechanism for the fluid to get sucked in under the part as it was being lifted up. Through suction forces, the fluid mechanics create a river of resin that gets to the deepest pixel at any given cross section. That gave a non-traditional approach for resin renewal at the build surface, which dramatically sped up the process.

But the gap was limited—it was 20 to 80 microns—so it was a mass transport– limited process. Chemistry can go way faster. We want to get a reaction rate–limited process. Even if we got 25 to 100 to 1,000 times faster, there would still be more room to go. That’s what we’re working on now. We have a new mechanism for getting liquid into that gap. We’re doing it through mechanical injection, not through suction forces. It’s through microfluidically created channels in the part that push liquid in. It opens up multimaterial printing and all sorts of stuff. It gets us another order of magnitude in speed. We’re very excited about that.

How does your work on medical implants differ from that on microneedles?

I was leading a center for cancer nanotechnology excellence at UNC, and the whole push was nanoparticles. The whole point of nanoscience in drug delivery is that you dissolve small molecules into a nanoparticle, and because nanoparticles are so much bigger than the molecule, it’s not cleared as quickly. You can have a much higher concentration of a chemotherapeutic in blood over time, and that was a key trick for better outcomes in preclinical animal models.

But that never worked on certain cancers, including pancreatic cancer. So we started focusing on that.

Unlike most tumors, which have a really rich blood supply—they are really red and bloody—pancreatic cancer tumors are as white as your eyeball. They’re very slow-growing. It’s now known that by the time someone is diagnosed, the tumors probably started 20 years earlier. When the cancer presents, it’s too late. The cancer will have wrapped itself around important blood vessels, the lymphatics will be blocked, and there will be a high hydrostatic pressure. If we insert a nanoparticle into the bloodstream, it’s basically going to go everywhere in your body except the tumor. We would have to ramp up the amount of drugs in the body to such a high level just to get some into the tumor, and these drugs are poisons.

A dear friend and collaborator of mine at North Carolina State University, George Roberts, was searching the web and told me at one point, “I heard you’re working in pancreatic cancer.” I said, “I’d love to work with you on this,” and started talking in very enthusiastic tones, but then I said, “How did you find out?” Well, he had just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He looked like you and me, just sitting at lunch. A week later he started chemo, and he looked terrible, just because of the chemo. So that’s the problem with this cancer.

We developed a device that uses minimally invasive surgery to surgically implant a selectively permeable membrane and an electrode right onto the tumor. The chemo has to have either a permanent dipole moment or be polarizable. We put a counter-electrode on the other side of the tumor, or outside the body. There’s enough of an electric current to drive molecules using what’s called ionic diaphoresis into the tumor. We worked with an amazing surgeon at UNC, Jen Jen Yeh, and a great MD/PhD student, James Bern, and we showed a 40 percent reduction in tumor volume on a preclinical animal model that had human tissue implanted in it.

Now we’ve built a company around this process, called Advanced Chemotherapy Technologies. We are having amazing progress, and we’re beginning to identify clinical sites for early 2023 clinical trials.

Are you concerned about the unknown environmental impacts of the materials that you are working with now?

Working in a polymer lab, you can’t help but feel complicit in the polymer pollution problem—microplastics and everything else. We’re working on new approaches for chemically recyclable resins in 3D printing. We don’t want to wake up 20 years from now having created an industry that has gone from prototyping and manufacturing to causing a whole lot of problems.

The solution takes both policy and business support. We need business policies that enable closed-loop markets and products, demanding that a company be responsible for the life cycle of their product, offering collection and reuse. I think that’s a great way to go, going forward.

Do you see any biases against this kind of technology when you look at replacing established technologies? Is it more difficult to get approved than by piggybacking on something that has a longer approval chain?

Everyone hates change. Comfort levels are high. That’s part of the battle. Change takes a lot of fortitude and dollars and experience.

Entrenched interests are front and center. Even with a cheaper way of making a denture, that savings is not being passed on to the consumer. How much of an embedded competition do you have to have for prices to come down?

You can lose a lot of spirit in this process. But the endgame is really impactful. We have a lot of people here that want to help. We’re in an environment where innovation and opportunities for making a difference to improve people’s lives are paramount. It’s inspiring to be in that kind of environment, and it’s fun to make a difference.

That’s where convergence comes in. It’s not just physical science, engineering, and medicine. I always use the analogy of, if your expertise is being an earthquake engineer for earthquake-proofing buildings, and you want to have an impact in Haiti, you need to know Haitian culture, the French language, and local policies for building codes. That is ultimately where convergence is.

What do you think is different about this idea of convergent science over other approaches that have been implemented in the past?

One way to sum it up is, What’s the difference between having a common language and being multilingual? There used to be the metaphor of an I-shaped person and a T-shaped person. The I-shaped person is really deep in an area, but doesn’t have the ability to collaborate. The T-shaped person is deep in an area, but could collaborate. Convergence is more about being cone-shaped or pie-shaped. You have to be deep in multiple areas. A T-shaped person is often dumbing things down into a common language to collaborate. Going deep in multiple areas is the domain of being multilingual.

If you’re going to be successful in this convergence area—for example, if you’re going to work on vaccines—you have to be deep in materials science, immunology, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics. There’s no shying away from it. You have to own it, at the deepest levels.

I know that you have a strong interest in diversity and equity. How do you address those considerations?

We spent most of this discussion on disciplinary diversity, but I will tell you, I’ve had a lot of young people come through my group, and if somebody grew up without much money, they approach problem-solving very differently than somebody who grew up with a lot of money. It’s not that one’s better than the other. They’re different. If you’re in the ideation world and you’re trying to drive innovation, you want to cultivate that difference because it is key for an innovation ecosystem.

I think it’s increasingly important in science to be relentless about diversity. You have to be clear about your values so you can be a destination for excellence, where people feel welcomed and included. But you have to be relentless about inclusion, because it doesn’t happen on its own.

Debra Rolison at the Naval Research Laboratory has talked about Title IX not just being limited to sports and federal funding. There’s a lot of truth to that. It’s been a long time since I’ve been at this, and things haven’t changed much. We have to do something fundamental.

A podcast interview with the researcher:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.