This Article From Issue

November-December 1998

Volume 86, Number 6

DOI: 10.1511/1998.43.0

Night Comes to the Cretaceous: Dinosaur Extinction and the Transformation of Modern Geology. James Lawrence Powell. 250 pp. W. H. Freeman and Co., 1998. $18.40, paper.

Geology has seen two great shifts in thinking over the past three decades. In the late 1960s, plate tectonics changed the prevailing views of how the earth works, and in the 1980s and '90s, extraterrestrial impact has come to be recognized as a major, if episodic, trigger for earthly catastrophe and a force behind the extinction and evolution of organisms and ecosystems. The impact revolution began with the masterful and lucky discovery of an iridium anomaly at the marine Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary near the Italian town of Gubbio by Walter and Luis Alvarez and their colleagues Frank Asaro and Helen Michel. Their 1980 Science paper set off a massive rush to test what had previously been the realm of rank speculation: the cause of the extinction of the dinosaurs and their world.

The resulting work on the K-T boundary has been unprecedented in its degree of interdisciplinary participation, cooperation and dispute. There were vertebrate paleontologists in arguments with geochemists in arguments with astrophysicists and more. The result is a spectacularly interesting story ranging across myriad disciplines. But it has been a difficult story to tell for two reasons. The first is the incredible breadth of subject matter, and the second is that the primary participants of the ongoing controversy have been the authors of the first wave of books; their proximity has colored their perspective. James Lawrence Powell's contribution is the first that successfully avoids both of these problems. A widely read geologist and museum director, he is an educated outsider to the K-T boundary controversy, and his book is a broad fresh look at the research on the end-Cretaceous extinctions.

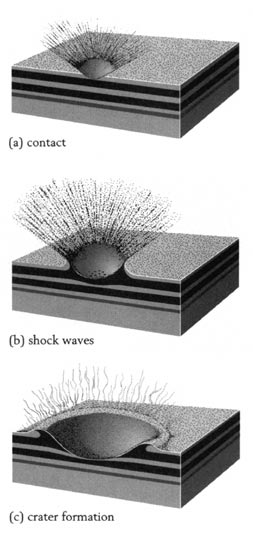

From Night Comes to the Cretaceous.

Powell starts at the Alvarez discovery and its context in a world of geology that thought, or at least acted, as if the earth was immune to extraterrestrial impact and its effects. Powell then plays out the early negative responses to the impact-extinction hypothesis and the eventual discovery and analysis of the giant K-T impact crater on the Yucatán Peninsula. He addresses the stickier biological and biostratigraphic questions of whether the impact actually caused the extinctions of plants, ammonites, foraminifera and dinosaurs. Finally, Powell takes the issue beyond the K-T boundary and plays with the idea that extraterrestrial impacts may be one of the main processes driving extinction and evolution since life began on this planet.

Walter and Luis Alvarez deserve, and have received, immense credit for the impact hypothesis, and this book shows how it was that such an unlikely idea came into existence. I was interested by the way that geologists convinced themselves that extraterrestrial impacts were not a significant process on earth. Grove K. Gilbert, one of this nation's most innovative geologists, analyzed Meteor Crater in Arizona in 1891 and concluded that it must have a terrestrial cause. His influence was so huge that it took NASA, and specifically Eugene Shoemaker (to whom the book is dedicated), to accurately reinterpret the crater some 66 years later.

From Night Comes to the Cretaceous.

The negative response to the impact-extinction hypothesis was natural at first, but as the evidence for impact mounted, a few individuals began to stand out as particularly vehement opponents. A strong proponent of the volcanic alternative to impact, Charles Officer, made significant contributions in the early 1980s by continually challenging the growing impact orthodoxy. Sadly, his latest book, The Great Dinosaur Extinction Controversy (Addison-Wesley, 1996) is more of a rant than a serious contribution to the debate. Powell directly deals with the awkwardness that occurs when entrenched scientists fail to yield to overwhelming data.

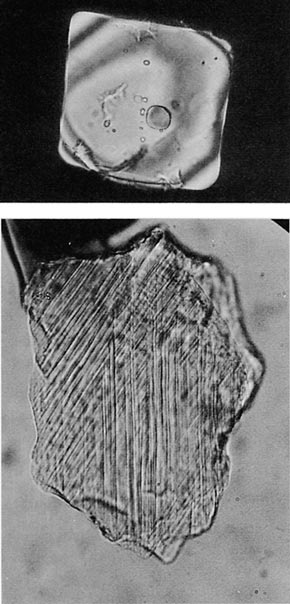

By this point in the book, Powell has come out as a firm supporter of the impact theory of extinction, and the path that he took to convince himself is clearly laid out. A point that he makes in the preface and again later concerns zircon crystals from a thin K-T boundary ejecta layer in southern Colorado that fingerprint the Chicxulub crater in the Yucatán as their source. This is significant because the crater from a specific collision, the K-T impact, can now be directly linked to its ejecta layer and the associated stratigraphic evidence for biotic extinction. If the impact did not have a causal relation to the extinctions documented at the precise stratigraphic level of the ejecta layer, then we are looking at the greatest cosmic coincidence in earth history.

From Night Comes to the Cretaceous.

Despite the stratigraphic coincidence of ejecta and extinction, the issue of whether the Chicxulub impact did cause the terminal Cretaceous extinctions remains one of the most contentious aspects of the debate. Like Officer, micropaleontologist Gerta Keller and a host of vertebrate paleontologists have actively opposed the impact-extinction hypothesis. Powell gives context for their protestations, implicates the weakness of their arguments and dismisses them. Using four major groups of fossils, he concludes that the case for extinction has been made. Although I agree with him, he failed to give the appropriate level of credit to palynologist Robert Tschudy of the U. S. Geological Survey, whose seminal work on plant microfossils made it possible for the iridium anomaly to be quickly found in terrestrial sections.

In the final section of the book, Powell takes his thesis beyond the comfort zone of many scientists, even some of the supporters of the K-T impact, and argues that impact was a factor at not only the K-T boundary but in many, perhaps most, of the other mass extinctions. To do this he relies on the periodic extinctions in the marine fossil record documented by Jack Sepkoski, the growing number of documented terrestrial impact sites and David Raup's provocative kill curve, which shows the average time between extinctions of different magnitude. Powell is certainly not the first to make this leap, but he makes it gracefully. The last chapter is a call to action and rightly argues that many of the questions raised in the K-T debates of the past two decades are resolvable by focused research. Although this reads like the conclusion to a grant proposal, it does allow the book to end with a clear idea of what we should do next.

Powell's style is entertaining, understandable and concise. He manages to tell the whole tale in 221 well-referenced pages, allowing the reader to speed through the whole controversy in an evening or so. Despite its brevity, this book presents the most comprehensive overview yet published of the K-T boundary controversy. I do have a minor criticism of the book's cover. Why is it that three books on the K-T boundary published in the past three years have illustrated their jackets with Jurassic dinosaurs? Surely Tyrannosaurus, Triceratops and the rest of the true victims of the impact are spinning in their ejecta-lined graves.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.