Child-Robot Interaction

By Yvette Pearson

What concerns about privacy and well-being arise when children play with, use, and learn from robots?

What concerns about privacy and well-being arise when children play with, use, and learn from robots?

Many robots are designed to take on social roles in schools, health care settings, and homes. But along with their increasing interactions with humans comes a growing problem: robot abuse. Although some high-profile incidents of robot abuse—such as the destruction of Hitchbot, the hitchhiker robot that traversed Canada without incident, yet met its demise in Philadelphia—have been attributed to adults, children also have a tendency to abuse robots. Abusing a robot may work against a child’s moral development by cultivating negative behaviors rather than virtues, so researchers are exploring not only the reasons behind this behavior but also its prevention.

NAVER LABS

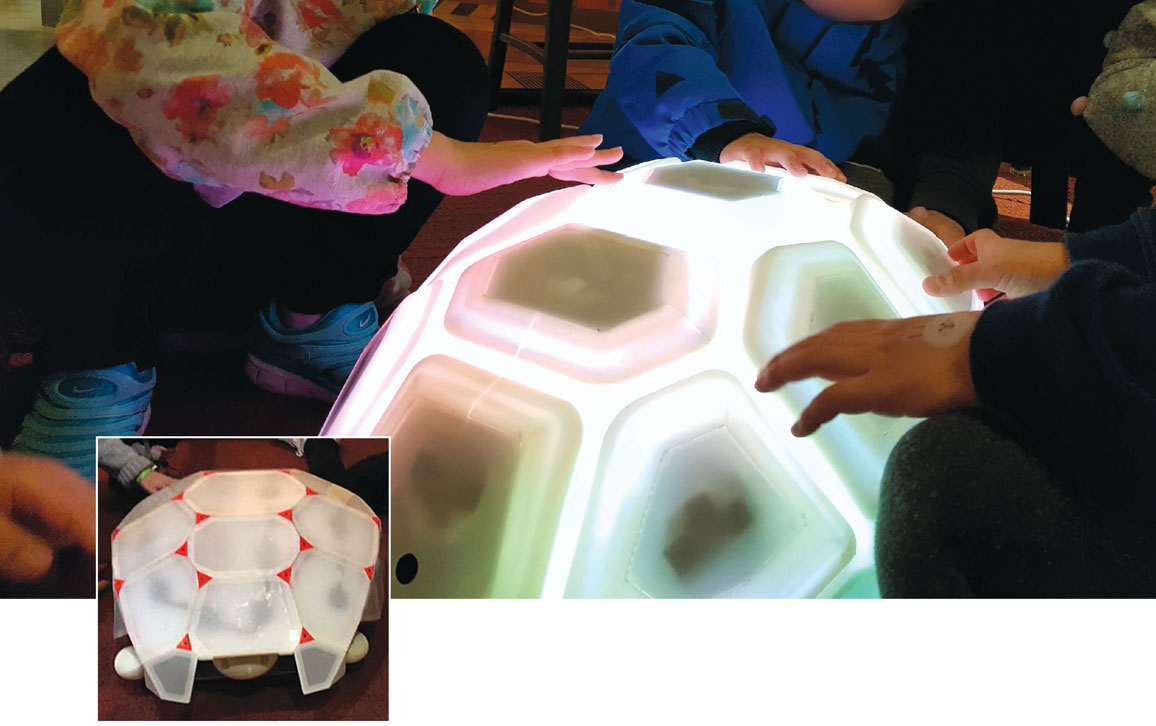

For example, at a conference in spring 2018, researchers from Naver Labs, KAIST, and Seoul National University, all of which are in South Korea, presented a new toy designed to discourage children from robot abuse. Shelly the robotic tortoise lights up and makes “happy” dancing movements with its limbs when it is petted gently. But if someone hits the robot too hard, it will retract into its shell and go dormant for a brief period of time.

Shelly’s creators expect that robots similar to Shelly can enhance child-robot interactions across various social contexts. Arguably, robots such as Shelly have the potential to encourage prosocial behavior and contribute to children’s moral development. Designing robots for children is a new realm, and along with the potential benefits these technologies present, they also raise unique concerns about a child’s attachment to a robot, a robot’s capacity to deceive a child, and the child’s privacy.

NAVER LABS / GIF by Robert Frederick

Experiments suggest that children may benefit from interactions with robots designed as playmates or as tutors in skills such as reading or writing. The use of technology-mediated games or other interactions to facilitate learning is an extension of a long tradition of using play for educational or therapeutic purposes. For example, one group of researchers from the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and the University of Lisbon in Portugal has configured a programmable humanoid robot to function as a “bad writer” and help children improve their handwriting by correcting its mistakes. The children are told that the robot needs to communicate in writing to successfully complete its mission and therefore requires the child’s assistance to create well-formed letters. Through teaching the robot to write correctly, the children have an opportunity to improve their writing skills and self-confidence.

Other robots, such as Charlie, My Special Aflac Duck, and Huggable, are designed to help children manage health issues. Each of these robots takes a unique approach to helping children cope with their conditions and treatments, including the loneliness and isolation associated with illness. Charlie has been used in a camp setting to help children learn about successful self-management of type 1 diabetes through educational games, praise, and constructive feedback; Charlie also engages with children’s feelings about living with their condition. My Special Aflac Duck is designed primarily to entertain and distract children undergoing cancer treatment, but it also helps patients identify and work through complex emotional responses to cancer treatment. Children can pretend to provide care for or perform medical procedures on My Special Aflac Duck.

Despite preliminary evidence that child-robot interaction in a variety of settings may benefit children, many people are concerned about the potential problems such technologies introduce, including risks to children’s welfare and privacy. For example, Huggable and My Special Aflac Duck are designed to comfort children who are hospitalized, but a child may form a strong attachment to the robot and be upset if it malfunctions, has to be replaced, or needs to be left behind when the child leaves the hospital. A related concern is that children may develop a preference for interacting with the robot rather than their parents, human caregivers, or peers and therefore become socially isolated. An additional problem is that parents and adult caregivers themselves might become overly reliant on the robots and fail to provide the level of care and comfort needed.

Robots designed for health care settings have not yet presented problems regarding children’s privacy, perhaps because these settings are subject to tighter privacy regulations or because such robots are unattractive targets for hackers or advertisers. However, some robotic toys commonly found in homes have raised concerns about children’s privacy, including Mattel’s Hello Barbie and Genesis’s My Friend Cayla doll. These dolls were initially designed to record their environment and access the internet to respond to a child’s questions. However, that capacity also creates the potential to collect and send personal information over a home wireless network to the company or other organizations, including law enforcement offices. In February 2017, My Friend Cayla was deemed an illegal eavesdropping device and banned in Germany.

Mark Lennihan/AP Images

In the case of Hello Barbie, the information was shared with ToyTalk, a company that analyzes data collected by the toy to maintain, develop, test, or improve its speech recognition and speech-processing technologies, but many parents have lingering concerns about how ToyTalk might use the data. The robotic toy has an indicator light that lets its users know when it is recording. The lack of clear regulations related to the collection, storage, and use of data leave the door open for inadequate protection of privacy, as in the case of Cloud Pets—whose data storage protection was so weak that in 2017 hackers were able to access 2 million voice recordings of conversations between children and their parents (the toys were subsequently taken off the market). Companies that sell data deliberately to third parties remain an ongoing issue.

Marina Hutchinson/AP Images

Multiple stakeholders have also warned of the potential negative emotional impact on children interacting with robots. Robot ethicists such as Amanda and Noel Sharkey of the University of Sheffield in England have identified deception, emotional attachments, isolation, and loss of privacy as key problems emerging from child-robot interactions. It is not clear, however, whether these problems are unique to children’s interactions with robots or the same issues emerge when children interact with humans. It is also not clear whether child-robot interaction leads to greater isolation than watching television or playing video games.

In my earlier collaborative research on the use of robots to assist with caring for older adults, we emphasized that robots should augment human-human interaction rather than replace it. Designing robots as assistants rather than replacements for human actors reduces the risk that human-robot interaction will lead to isolation. One observation from this earlier work was that many of the concerns raised about human-robot interaction had been overlooked when the same troubling phenomenon was present in the absence of robots. For example, although some critics have expressed outrage at the possibility of leaving a child alone with a robot companion, they often fail to consider that the behavior of parents who are emotionally immature or obsessively distracted by their wireless devices can also contribute to children’s feelings of isolation or insecurity. The presence of a robot, especially one that appears to give the child its undivided attention, could mitigate negative effects of problematic adult behavior on children’s emotional well-being.

Deceptive practices are common among humans, perhaps especially in interactions between adults and children—for example, many parents perpetuate the myth of Santa Claus or proclaim that their child’s scribbled paper is an impressive work of art. Developing emotional attachments to either persons or things is not risk-free. It remains an open question whether emotional attachments to robots are more detrimental than some attachments to people. Although nothing appears to be inherently bad about a child forming an attachment to a robot, and attachments to robots appear to be no worse than attachments to other physical objects, such as toys, this bond could be exploited by nefarious actors. A company may use the child’s attachment to a robot to extract private information from the child, encourage the child to purchase products, or manipulate the child in some other way.

The researchers who created the “bad writer” robot reported that after the study, one child wrote a letter to the robot asking how its mission was going. This example suggests that the child formed enough of an attachment to the robot to want to continue interacting with it and to express some concern about its well-being.

The attachment itself is not usually problematic, but rather people’s and companies’ exploitation of attachments can generate problems. For instance, if a company uses child-robot attachments to collect information about a child so as to tailor marketing to their tastes, interests, or vulnerabilities, this use of data would be problematic. It is reasonable to assume that if robot-mediated marketing to children proves effective, companies might use it in the future.

An issue unique to child-robot interaction is that children are considered incapable of providing genuinely informed consent.

Children have already been persuaded by Facebook’s “friendly fraud” to spend hundreds of dollars without their parents’ permission on in-app purchases while playing games. It would not be a stretch to think that a robot, especially one with whom a child has developed an emotional attachment, could persuade a child to spend money on upgrades to its software or on some other product that sounds like fun to the child. If information were collected about the child’s interests, companies could do targeted advertising to encourage the child to get desired items.

Similarly, the deception involved in child-robot interactions, such as the child believing that the robot experiences emotions or other internal states or is a true friend, may become problematic only in certain contexts, such as situations in which the child’s interactions with their robot companion are not balanced by parent-child interactions or social activities with peers. Children’s attachment formation with robots can become problematic when there are deceptive design features or data collection that enables loss of privacy, along with the related potential for damage to children’s welfare.

An issue unique to child-robot interaction is that children are considered incapable of providing genuinely informed consent. A child interacting with Charlie or My Special Aflac Duck may not have a good sense of what information the robot is collecting during their interactions, or with whom it will be shared, much less an understanding of the long-term consequences of sharing personal information. Parents typically determine what and with whom information about their children is shared (for example, doctors, teachers, or caregivers). It remains unclear whether parental consent to child-robot interaction can adequately protect children’s long-term interests.

Rob Stothard

Given the relative newness of robotic technology, its ever-expanding abilities, and most users’ lack of understanding of the likely consequences of interacting with robots, many parents might not fully understand what they are permitting when they allow their children to use robots. Parents who purchased Hello Barbie or My Friend Cayla probably thought they were buying an engaging toy for their child and failed to anticipate the toy’s ability to intrude on their privacy in ways that could put themselves or their children at risk, such as by learning family members’ routines and inferring when the home would be occupied or when and where a child might be left unattended.

The context of child-robot interaction raises questions about what kind of information robots should collect, how that information should be used, and by whom. A robot designed to help children develop skills should be able to detect where a child left off in their reading or mathematics lesson so that it can pitch subsequent interactions in a way that will be appropriately challenging and will prevent the child from becoming bored.

There is some concern about whether this information should be stored only locally in the robot or uploaded to a manufacturer-owned cloud. The data collected have the potential to assist the creators of the technology with maintaining, detecting problems, and making improvements to the robot.

Although these are legitimate reasons for collecting and using this information, personal information would be embedded in the data. Without a person’s consent, using and sharing their information violates their privacy. Those with whom the child lives and interacts (for example, parents, peers, and other visitors to the child’s home) also risk inadvertently sharing information well beyond the confines of the relationships they have intentionally established.

Ideally, those who collect data would be good stewards of information, using it only to improve the technology for end users. But one can imagine a company selling data to other companies interested in the development or marketing of new products for children. Even if a company is transparent about its proposed use of the information, one cannot assume that either the sale of the information or the third party’s subsequent use of it is ethically defensible. The sale of information would likely violate users’ privacy, and the third party’s use of the information has the potential to cause harm. For instance, if someone mentions illegal substances, prescription drugs or alcohol, or having certain medical conditions, sharing this information could lead to social stigma, loss of employment, legal penalties, loss of benefits, or damage to the person’s reputation.

Alongside the potential harms, however, the collection and use of information has the potential to protect children’s welfare. For instance, if a child relays information to a robot such as Hello Barbie that suggests neglect, emotional maltreatment, or abuse, the robot could be designed to notify a parent, guardian, or social worker.

In some jurisdictions, a company with access to a child’s data may be legally required to report suspected neglect or abuse.

Although robotic toys do not currently initiate investigations into child abuse, some evidence suggests that robots might be better than humans at collecting information from children about mistreatment. For example, a 2016 study by Cindy L. Bethel of Mississippi State University and her colleagues indicated that children were more likely to report bullying to a robot interviewer than to a human. Moreover, recent news stories about law enforcement using data from fitness tracking devices in criminal investigations suggest that robotic toys may provide similarly valuable information in child-abuse cases.

Designing a robot that can recognize when information shared by a child should be passed on to a parent or another trusted adult will be a challenge. If this information becomes available to a company collecting data for other purposes, the company could alert child welfare protection authorities. In some jurisdictions, a company in possession of such data may be legally required to report suspected child neglect or abuse. The possibility of incurring a legal obligation to report might sway some companies to think carefully about their data collection practices.

In addition to responding to (and collecting data about) what children say and how they behave, some robots now have facial recognition technology, which introduces new concerns. For example, in some preschools across China, robots are used regularly to analyze children as they arrive and determine whether they might be infected with a contagious condition, such as conjunctivitis, and should be sent home.

Xu Kangping / Imaginechina / AP Images

Facial recognition technology may be used to detect subtle facial features, involuntary reactions, or even microexpressions associated with emotional states or, as in the case of the Chinese preschools, medical conditions. The use of facial analysis in preschools raises concerns about the possibility of misdiagnoses, which may result in children being sent home needlessly, disrupting their day and their parents’ work schedules. There is also a concern that the analysis might pick up a condition that the child’s parents are managing successfully and have chosen not to disclose to the preschool or even to the child.

There are multiple possible uses of facial recognition technology that raise concerns about individuals’ ability to control others’ access to information about themselves. For example, Affectiva is a company whose multifaceted work involves developing facial analysis algorithms that will enable robots to respond to and monitor people, examining such things as drivers’ alertness and mood or shoppers’ microexpressions. This functionality could be viewed as particularly invasive, especially if these monitoring and inference abilities bypass an individual’s ability to decide whether to share information in the first place. Beyond monitoring, companies might use the information to “nudge” people in a particular direction—for example, to buy their products. Although parents and other caregivers view it as part of their duty to nudge children to behave in certain ways, nudging from other actors has the potential to be problematic if it is not regulated carefully.

The recent use of artificial intelligence (AI) by Amazon to recruit employees and by judges to predict recidivism has been plagued by problems: Algorithms have been found to show bias, and researchers have used poorly curated yet large and freely available data sets to establish “ground truths” (see “Trust and Bias in Robots” in the March–April 2019 issue). The collection, storage, and use of these biometric data raises questions about whether people’s interests can be adequately protected when they may be unaware that this information about them is being collected in the first place and have no idea how it is subsequently used to train AI systems or for other purposes, some of which may cause harm, especially to those who may already be socially marginalized.

Although the potential pitfalls of child-robot interaction must be acknowledged, it is important not to lose sight of the multiple ways that children stand to benefit from their interaction with robots in different settings, such as in health care, in school, or at play. Whether child-robot interaction also promotes children’s long-term well-being is in the hands of designers, manufacturers, distributors, and other adult decision-makers. The burden is on them to ensure that child-robot interactions do not stifle children’s development or limit their future opportunities and that any private information about the child collected during those interactions is used only in ways that will promote the child’s well-being.

Groups such as Responsible Robotics are already engaging with policy makers and raising public awareness about potential ethical problems related to the design and use of robots and other emerging technologies. For products marketed to children, the Federal Trade Commission’s kidSAFE Seal “safe harbor” program encourages companies that provide online sites or technology services, including connected toys, to safeguard children’s privacy. One version of kidSAFE certification requires compliance with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA).

Companies that market and maintain robots designed to interact with children should provide clear information to consumers about the abilities and limits of robots, including what kind of information they collect from users, how they collect it, where they store it, and who has access to it. Companies will need to meet the challenge of helping parents, teachers, and children fully understand the risks of data sharing that emerge through child-robot interaction while also acting in ways that will minimize those risks. Mattel’s most recent version of frequently asked questions about Hello Barbie provides details about how children’s privacy is protected and notifies consumers that Hello Barbie is kidSAFE and COPPA compliant. Robots such as Charlie and My Special Aflac Duck are used in more controlled settings—either experimental settings or health care settings—both of which place greater emphasis on informed consent and privacy protection. My Special Aflac Duck is available only to children diagnosed with cancer and will be delivered only to licensed health care facilities authorized by the company to receive the device. It collects information through the use of its associated app, but the device identifier is hashed, making it very difficult to track to a specific person.

Companion robots for children are gradually finding their way into different areas of people’s lives, often in ways that improve children’s experiences or help them develop useful skills. It will be important to ensure that these benefits are not eclipsed by the risks that may accompany emerging technologies. Ongoing, ethically informed dialogue is needed among engineers, industry partners, consumer advocacy groups, and others concerned with ethical issues related to emerging technologies—especially those likely to effect child development and welfare. These groups should work with policy makers to formulate and implement federal regulations and industry standards that are likely to contribute to human flourishing.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.