This Article From Issue

May-June 2011

Volume 99, Number 3

Page 262

DOI: 10.1511/2011.90.262

GEOGRAPHIES OF MARS: Seeing and Knowing the Red Planet. K. Maria D. Lane. xiv + 266 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2011. $45.

What can yet another history teach us about the canals of Mars? In the case of K. Maria D. Lane’s new book, Geographies of Mars, the answer is,“a surprising amount”—about ourselves, our institutions and our authorities, and about what constitutes evidence and argument; the list is very long. The volume is an exceptionally well-written and cleverly crafted exposition of what both speculative and mainstream science had to say in the late 19th and early 20th centuries about the nature of Mars and the beings that might inhabit it; Lane situates this history in the broad cultural landscape in which the emerging professions of both astronomy and geography were being planted, tested and nurtured.

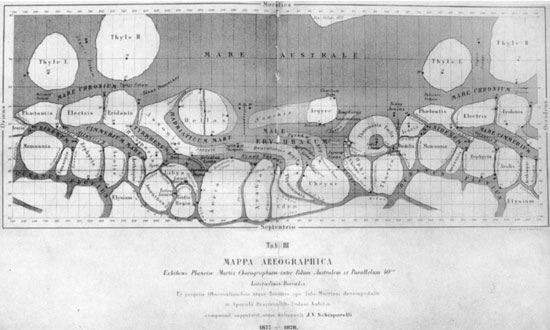

From Geographies of Mars.

Lane’s book appears at a time when there has been a welcome resurgence of scholarship recasting and extending humanistic explorations of the debate over life on Mars that took place in that era. Geographies of Mars provides insights that help the reader appreciate the resurgence. Lane avoids specialist jargon, making this literature accessible to readers whose background is in the sciences rather than the humanities.

In six taut and closely reasoned chapters, the author, an assistant professor of geography at the University of New Mexico, introduces the historical debate and the literature that has examined it from various perspectives. The idea that there were canals on Mars began with Giovanni Schiaparelli, who followed Mars through the weeks of its perihelic opposition in 1877 and for several months afterward, making his observations from a rooftop cupola in Milan with an 8-inch Merz refractor. In 1878 he published a memoir of his observations, which included a detailed map of the northern hemisphere of Mars showing islands and peninsulas divided by narrow blue bands of water that he labeled canali (Italian for channels); these soon became known as canals in the English-speaking world. Although no one confirmed his observations until 1886, the map was hugely influential, for reasons that include the regard in which Schiaparelli was held and the perceived objectivity of cartography. Updated maps of the canals that Schiaparelli produced in the 1880s became more and more abstract and geometrical. In 1895, the American amateur astronomer Percival Lowell argued that the “unnatural” and “artificial” appearance of the canals suggested that there was intelligent life on Mars, and he began producing his own detailed maps showing even more canals. He wrote books, went on lecture tours and spoke out in the popular press, making many claims about the landscape and civilization of the planet—that Mars was growing increasingly arid as a result of planetary evolution (and that a similar future awaited Earth), and that this had led the inhabitants to unite in peaceful cooperation to ensure a water supply. Many professional astronomers were quite critical of Lowell, but it wasn’t until 1907, when photographs of Mars failed to show the canals, that his maps began to lose their authority. By 1910 most astronomers had concluded that the supposed canals were an optical illusion.

The combination of conditions under which Schiaparelli made his observations has always made me skeptical of what it was he was seeing, and there are no new scientific explanations in Lane’s book. But by the time I finished reading her third and fourth chapters, I better understood why Schiaparelli’s work was so appealing, and indeed why followers of his such as Lowell were as effective as they were in keeping the idea alive that a morally, socially and technically advanced civilization existed on the planet—a populace that, over millennia, had been driven by necessity to evolve into beings capable of reorganizing the geography of their dying home at a global level in order to survive and, evidently, to prosper.

Of course, those beings I speak of as inhabiting Mars are humans. They are us. Lane’s book has convinced me of this, satisfying the suspicions first raised in me by pioneering historical works by William Graves Hoyt, Steven J. Dick and Michael J. Crowe in past years, more recently followed by David Strauss’s excellent 2001 cultural biography of Percival Lowell. My suspicions were greatly heightened by Robert Markley’s recent Dying Planet: Mars in Science and the Imagination (2005), a study that neatly juxtaposes fact, speculation and popular fiction. One can find this idea in all these works, more or less. But the realization didn’t hit me until I read Lane’s explanation of why the popular image of a socially and technologically advanced civilization on Mars was distinctly, though not exclusively, an American cultural phenomenon. She relates the very existence of that image to a deep-rooted but definitely flawed belief among Americans that has been described as exceptionalism. In the conclusion to her book, she quotes cultural geographer Fraser Macdonald’s observation that the exploration of space, “from its earliest origins to the present day, has been about familiar terrestrial and ideological struggles here on Earth.” One can see clearly from the scope of Lane’s work how contingent the appeal of advanced life on Mars must have been upon the American popular self-image.

Lane’s physical and human geographical exploration plows through both the scientific investigations and the cultural reactions. For many readers this will be familiar ground. But it is ground tilled in a very different pattern, allowing for a broader interpretive cut. By employing both descriptive and explanatory arguments from cultural or human geography, and by showing how these elements influence not only the production of knowledge but also its dissemination and the subsequent assignment of authority, she manages to put into better focus issues that have been acknowledged in more traditional historical treatments (including my own), so that they can now be appreciated for what they are, not just within professional communities but in culture writ large.

Let me offer an example of how the book was helpful to me. I did a brief study in the 1970s, well summarized in Lane’s book, regarding the spectroscopic search for water on Mars in the early 20th century, which I took to be the most sensitive indicator of the state of the art of scientific practice in that day, more objective than squinting at canals. I highlighted an episode in which astronomer William Wallace Campbell took his spectrographs to the highest and driest peak in the Rockies to rid his data of as much earthly contamination as possible. In my mind, the fact that the observations were conducted at high altitude was enough to lend authority to them, and I did not belabor the obvious. However, I never considered the possibility that their authority also arose from the extreme effort itself—the fact that they were made after an expeditionary effort to an exceedingly remote and hostile place. The expedition was a defining career milestone for Campbell, even more so than those on which he chased solar eclipses around the globe. In the larger context that Lane provides, I can better appreciate the depth of Campbell’s frustration when his authority was called into question by negative popular reaction. I can also better appreciate why astronomers were so deeply frustrated by Lowell’s challenge of their hegemony, a challenge that went far beyond the issue of site superiority to the question of the legitimacy of professional scientific practice.

Readers of Geographies of Mars who begin the book feeling satisfied with purely psychological or physiological explanations for why observers found canals on Mars in the Schiaparellian and Lowellian era will come away with an enlightened appreciation of how complex the problem really must have been. The book is a must-read for any historian or scientist who cares about what, how and why, and to what extent, cultural forces shape both scientific knowledge and public reaction to it.

David H. DeVorkin is Senior Curator, History of Astronomy and the Space Sciences, at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution. He contributes to historical scholarship in his areas of curation and recently built a free public observatory on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.