Symmetries Obeyed and Broken

By Peter Pesic

A review of Lucifer's Legacy: The Meaning of Asymmetry, by Frank Close and Antimatter: The Ultimate Mirror, by Gordon Fraser.

A review of Lucifer's Legacy: The Meaning of Asymmetry, by Frank Close and Antimatter: The Ultimate Mirror, by Gordon Fraser.

DOI: 10.1511/2000.41.0

Lucifer's Legacy: The Meaning of Asymmetry. Frank Close. 259 pp. Oxford University Press, 2000. $27.50.

Antimatter: The Ultimate Mirror. Gordon Fraser. 213 pp. Cambridge University Press, 2000. $24.95.

Popularization has its perils. It is hard enough to recount complex theories and experiments clearly, harder still to make them accessible and attractive, and hardest of all to rouse the reader from unreflective passivity. As a reader, I may at first be content only to gaze at the mysteries of science with mute admiration. In the end, though, if I cannot begin to think about these mysteries on my own, I may lose interest and turn away in despair or disgust. Or I may feel cheated, as if I had come to a great banquet and read the enticing menu but had come away unfed.

Like other popular works about science, these two books confront a hunger in readers for a deeper understanding of science and must be judged in part on how well they satisfy it. They both treat the symmetries of nature, but they approach them differently.

Lucifer's Legacy concentrates on the importance of asymmetry. (The title refers to the author's encounter with a striking violation of the formal symmetry in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris, a statue of Lucifer whose fallen head seems to spoil the garden's perfect design.) Beginning with the symmetries of the human body and brain, Frank Close, a physicist and broadcaster, discusses the left- and right-handedness of molecules and the important asymmetries of organic compounds crucial to life. His examples are fascinating and often fresh. He makes only a few missteps (the last chord of Bach's St. Matthew Passion is not simply unresolved, nor does the color range of visible light span the interval of even one octave in frequency, as he says).

He tells the story of modern physics from the discovery of x-rays to the symmetries obeyed and broken in the atomic and nuclear realms. Throughout, his presentation is lively and charming. One can readily imagine him linking several children hand to hand to form a human battery, as he describes having done when he lectured in 1993 in the famous series of Christmas talks at London's Royal Institution.

Although Close's examples are sometimes homey, they are not condescending, because he engages the reader in a real process of thought. For instance, he pauses to wonder about ordinary mirrors. Do they really reverse right and left? What about up and down? We are invited, directly and unpretentiously, to think it through with him, and he helps us consider the options without foreclosing our own reflections. When you think it through, with his guidance, the answer is surprising and rather wonderful. These are the finest moments in the book, and readers will come away not merely having heard about physics but having thought about it for themselves.

Gordon Fraser, a science writer and editor at CERN, the European laboratory for particle physics, covers much of the same ground in Antimatter, making that intriguing topic his central theme. Fraser concentrates on the development of quantum physics leading to the prediction and observation of antimatter, from the theories of Dirac and Feynman and their experimental consequences up to such recent developments as positron emission tomography (PET) and the production in 1995 of antihydrogen, as well as the bizarre schemes using antimatter in the "Star Wars" defense system. He is at his best giving a nice overview of the sweep of experimental physics in recent decades, managing to include a great many discoveries and ideas despite the brevity of his book. Perhaps because of this broad scope, Fraser does not pause to wonder and to question.

From Antimatter.

Take the image of a mirror, especially antimatter as "the ultimate mirror" of matter. Though attractive, this analogy remains somewhat confusing. Fraser mentions in passing that mirrors reverse left and right, whereas Close leads us to question that commonplace. How can we think about antiparticles as mirror images of particles if we can't get straight what a mirror does in the first place? This is especially true since it emerges that the antimatter "mirror" changes what it reflects, for nature can distinguish between left and right.

If the reader is to follow such strange ideas, many questions need to be raised and addressed more carefully. For instance, how could gravity ever become a repulsive force? How could cosmic inflation proceed faster than the speed of light, as Fraser tells us it does? Since the author does not help us think about such questions, we can merely admire the incomprehensible exploits of scientists that he describes, without much clue as to how one could ever make sense of them.

Fraser does provide some engaging details that enrich his exposition, and one is grateful that he includes such figures as Hans Dehmelt, the thoughtful "master trapper" of matter and antimatter, who deserves far greater renown. Yet much of Fraser's history is schematic and unquestioning. Sometimes this simplified approach leads him to misrepresent history. Fraser gives an account of the origins of quantum theory in terms of reaction to a presumed "ultraviolet catastrophe." In this, he is following the regrettable precedent of many scientific textbooks that give this version. The physicist and historian Martin J. Klein long ago showed that Max Planck knew of no such "catastrophe" when he made his first steps toward the quantum in 1900. That "catastrophe" was only formulated years later, then taken up by textbooks to make the course of history seem simpler.

Elsewhere, Fraser implies that followers of "the powerful Socrates" were skeptical of atomism because it clashed with his "dogma," unaccountably ignoring that thinker's oft-reiterated claim to know nothing, to promulgate no dogma. Questions about atomic theory are not just dogmatic objections. Also, Fraser's claim that the atomic theory was "ready for the textbooks" in 1860 is based on a simplistic notion of scientific truth and ignores the fact that a number of distinguished scientists doubted the reality of atoms well into the 20th century.

Fraser's historical account of more recent figures seems more accurate, as if he had been careful to consult scientific advisers to avoid gaffes. One wishes he had been as assiduous in exploring what thoughtful historians of science could have taught him.

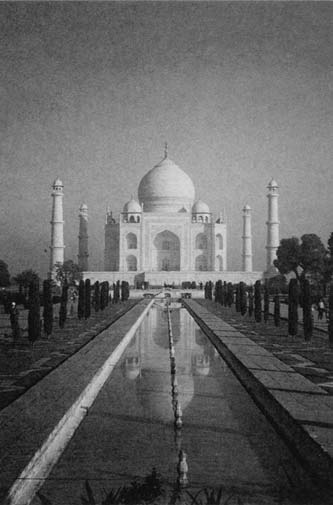

More fundamentally, Fraser is not clear about the significance of asymmetry. For instance, he uses the image of the Taj Mahal to illustrate "perfect but nevertheless superficial symmetry" and to serve as an analogy: "Like the grand plan of the Taj Mahal, perhaps antimatter is there to ensure an overall superficial symmetry which we can no longer see from our viewpoint." This is deeply puzzling, especially the word "superficial," which suggests that the symmetry should be obvious or apparent. So far as is now known, the universe apparently does not contain equal amounts of matter and antimatter, and in that way is not symmetrical. Then what has happened to Fraser's symmetric image of the Taj Mahal?

In contrast, Close emphasizes the crucial importance of deviations from symmetry, especially in the development of life. Unlike Fraser, who simply identifies beauty and symmetry, Close notes that deviations from symmetry are critical in visual design. A Persian rug, it is said, always includes a telling "flaw," enhancing its beauty while acknowledging the limits of human art.

A popular treatment can also be thoughtful. A good reporter probes and asks hard questions to help his readers delve deeper. Perhaps because he is also a physicist, Close is readier to ask such questions, and this gives his book added value. Unfortunately, both books lack substantial notes giving sources or suggestions for further reading, leaving readers without guidance if they wish to learn more. In their different ways, these books show how important it is for readers to be shown the central questions and encouraged to think for themselves.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.