Sumptuous Science

By Dianne Timblin

Three recent releases demonstrate just how vibrant science-related titles can be.

Three recent releases demonstrate just how vibrant science-related titles can be.

Not so long ago, when digital books were ascendent, avid readers would speculate from time to time about the future of print books. As the number of readers browsing print copies of newspapers and magazines dwindled, it seemed plausible that book readers might migrate en masse as well.

But for the past two years, until a recent 2.4 percent uptick, digital book sales have stagnated and, for a multitude of reasons, print books don’t appear to be destined for the endangered species list anytime soon. For this, as a reader, reviewer, editor, and certified book addict, I am grateful. Although there’s nothing handier than being able to carry the equivalent of a bookcase full of titles on a device the size of a paperback, it remains true that some books are best experienced on paper. And in a few cases, the full wonder of a title may be otherwise lost.

Such is the case for an impressive clutch of recent releases. Each will richly reward readers who leaf through their pages, linger over their images, and launch into the text. Moreover, each demonstrates how vibrant and gorgeous science-related titles can be.

The experience of reading Terry Burrows’s The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles (Thames and Hudson, 2017) is akin to strolling through a thoughtfully staged museum exhibit on the history of sound recording and playback—one that presents technology matter-of-factly while also dipping into pop culture. The book is divided into chapters representing four eras of audio evolution: acoustic, electric, magnetic, and digital. Sections of patent drawings punctuate the transitions between chapters, and it’s easy to lose yourself in their details as you take in the change over the decades from the elegant mechanics of the acoustic era to the intricate circuitry threading through digital devices. (One patent illustration, submitted by the Victor Talking Machine Company in 1927, depicts an instructional tag that offers a suggestion that remains refreshingly useful: “Read your Instruction Book carefully—it will save you expense and trouble.”) Each chapter opens with a timeline that anchors its topic and is followed by a lucid essay by Burrows, an author who specializes in music history, that discusses the developments of that era and effectively contextualizes the images to follow. These images—delightful, varied, and attentively captioned—make up the bulk of each chapter, and rightfully so.

The real stars are Simon Pask’s copious photographs, which manage to be both luscious and crisp, of items from the EMI archives. From a 1902 gramophone that played discs made of chocolate, to a 1940 U.S. Army–issued wind-up record player for use in war zones, to a shiny array of Sony Minidisc Walkman devices from the 1990s through the early 2000s, these artifacts transfix. I’d encourage anyone who suspects that technology and beauty are antithetical terms to spend time immersed in these pages.

Left: Interfoto/Alamy Stock Photo, Right: EMI

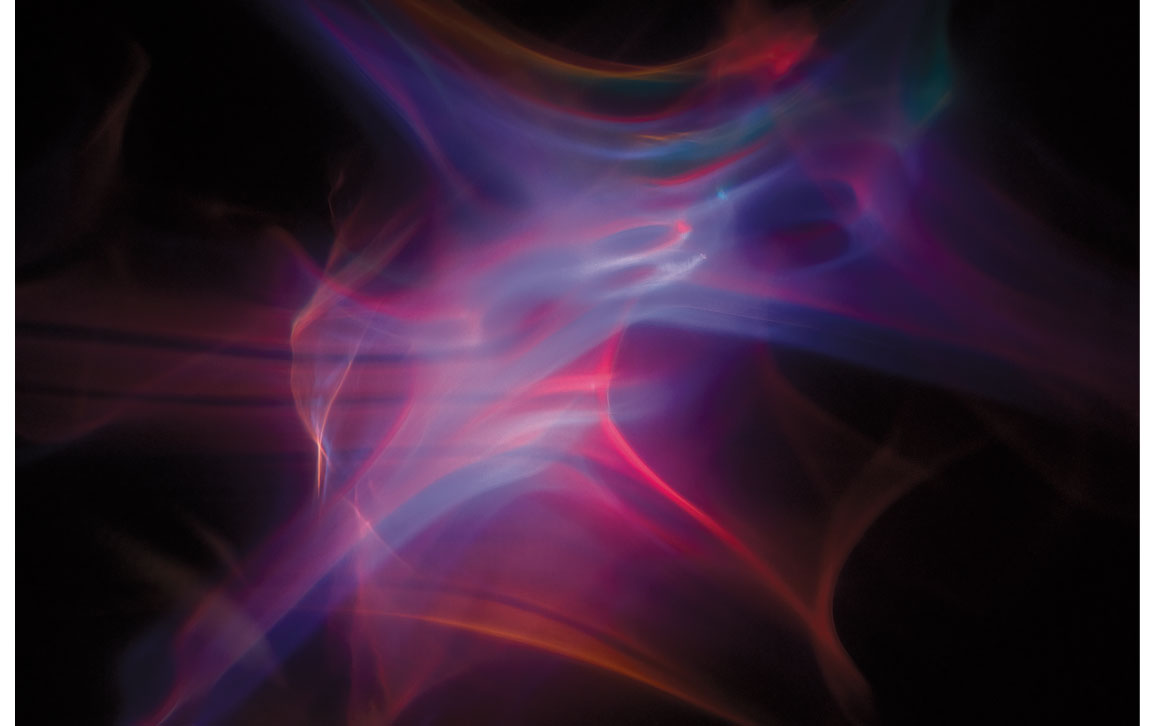

Instead of sound, Keely Orgeman lavishes attention on light in Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light (Yale University Art Gallery and Yale University Press, 2017). The book’s release coincided with the opening of an exhibition of Wilfred’s work earlier this year at the Yale University Art Gallery, where Orgeman curates American artwork. Lumia is the first book devoted to Wilfred’s work in 40 years, and it aims to introduce the artist to new generations.

Enthusiasts familiar with contemporary artists such as James Turrell (who contributes the book’s foreword), Jenny Holzer, and Olafur Eliasson, whose light-based installations are well-known and widely exhibited, may never have heard of Thomas Wilfred, who pioneered the art form. (His name for the medium, lumia, never caught on.) His experiments with manipulating light into art began in 1919, which meant that it was necessary for him to invent many of the technologies that made his work possible. Early in his career, he focused on producing vibrant, abstract performance artworks composed of vividly hued, sinuous light forms that would flicker, swell, and diminish on a projection screen for audiences who would watch the complex interplay of colors. The effect calls to mind the aurora borealis, and that style of projecting light remained his signature throughout his career. Wilfred invented a device, which he dubbed a clavilux, for these performances; it resembles modern soundboards, and he’d play it somewhat like an organist. Although the performances were silent, he thought of them as orchestral, and he named his work in the style of symphonic music, a practice he continued after moving on to create installations that played automatically, many of which were designed to project a flow of spontaneously generated light forms (that is, they didn’t repeat) and a few that were designed to be enjoyed in the home. These later works, which began appearing around 1930, prefigured the television, yet the devices look like wooden cabinet TVs if they’d been made by modernists.

Lumia makes it clear why Wilfred deserves a spot in the 20th-century canon, and Keely does a terrific job discussing not only the artistic merits of the work, but also its significance in the context of the technology and physics of the time. “Broadly speaking, Wilfred’s precise light-bending technique mimicked that of physicists’ laboratory experiments,” Keely notes, “which often used angled mirrors to test the velocity of light when its path was redirected by reflection. The sophistication that the artist demonstrated in his technical work shows his deep understanding of the behaviors of light—how it traveled and how it interacted with other elements in its environment.” Essays contributed by a historian, a curator-conservator pair, and a media studies scholar, focusing, respectively, on Wilfred’s art in a postwar context, on the process of conserving the works’ mechanical structures, and on the artist’s legacy, make for fascinating reading as well. The still images of Wilfred’s works do not disappoint, and photos of the equipment he developed and some of his conceptual drawings are helpful and revealing.

Incidentally, the Wilfred exhibition shown at Yale has traveled to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where it will be on display until January 8, 2018. Seeing these works in all their performative glory could well be worth a trip to the capital— there are some things even the most beautiful book can’t capture.

From Lumia.

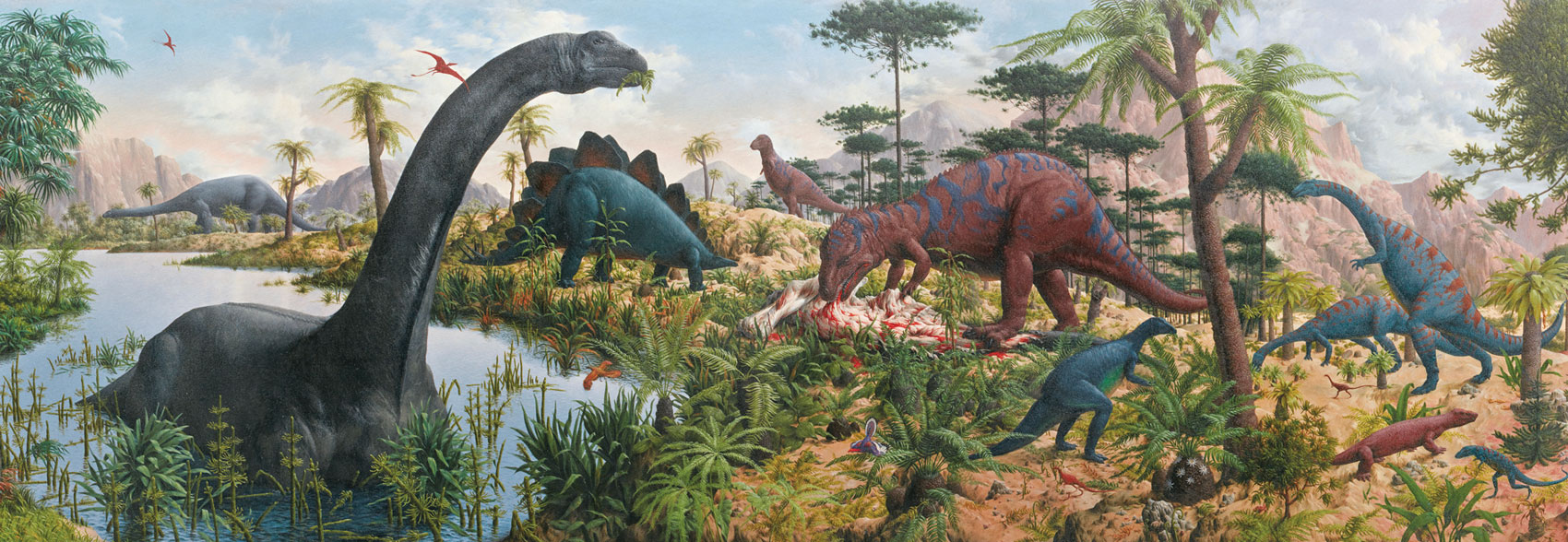

That doesn’t mean authors and publishers won’t try, though, and sometimes the effect is downright dazzling. The juggernaut of this fetching group of volumes is Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past (Taschen, 2017), by Zoe Lescaze, a writer whose background includes art history and archaeological illustration. Paging through it is like taking a time- and space-bending, multicentury global tour of natural history museums and amusement venues and getting to compare what scientists and artists from era to era believed prehistoric creatures must have looked like.

The experience begins before you’ve even opened the book. The cover’s pebbly, reptilian surface may take a few minutes to discover, as its jacket has been designed to stop readers in their tracks. There they'll encounter a grotesquely beautiful painting of an Inostrancevia shown in profile, its hide flecked with coppery foil that lends its tawny folds dimension. Crimson viscera dangles from its fangs like a holiday garland. Its amber eye gives the impression of regarding the viewer with cool contemplation. Painter Alexei Petrovich Bystrow has emphasized the mammal-like appearance of the saber-toothed reptile and his creation seems to exist, powerfully and unnervingly, in an interstitial world. Its body plan caught between the reptilian and the mammalian, Bystrow’s Inostrancevia appears to inhabit a time that is at once ours and its own.

In fact, that visual collapsing of time—whereby ancient creatures appear to have traveled forward in time—is a hallmark of Paleoart. Across its pages, readers may certainly track the advance of paleontological knowledge, but they can also take in the effect of different modes and fashions of painting. Some of these modes make for stunning paleoart. Works by mid-20th-century English artist Maurice Wilson, who had an affinity for Japanese and Chinese painting techniques, exhibit rare warmth and delicacy. Lescaze points out that Wilson was known for “eschewing three-dimensional illusionism altogether,” rendering stylized scenes that draw and hold the viewer’s eye. His watercolor of an archaeopteryx, depicted in russet and golden hues, perched on a branch with its wings spread wide, is simply breathtaking.

Lescaze proves an intrepid guide through the scientific and artistic eras, and her lovely writing and good humor make the text a pleasure to read. This is a huge book—in size (oh, the stunning pullouts and gatefolds!) and in stature. Many books about prehistoric life cross my desk in a given year, but I’ve never seen anything like this.

Image courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

The measure of a book is usually tallied by page count, binding style, or physical dimensions. For these three titles, I offer instead their combined weight, which is nearly 20 pounds. A strong bookshelf is a must for these volumes—but in exchange, readers can expect hours of enlightening enjoyment.

Dianne Timblin is book review editor for American Scientist.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.