Short takes on three books

By David Schoonmaker, Greg Ross, Elsa Youngsteadt

The Model T • American Pests • Flotsametrics and the Floating World

The Model T • American Pests • Flotsametrics and the Floating World

DOI: 10.1511/2009.79.348

THE MODEL T: A Centennial History. Robert Casey. Johns Hopkins University Press, $24.95.

I’m a classic car buff who rarely reads books about classic cars. So Robert Casey’s The Model T: A Centennial History caught me by surprise. I opened it to chapter 5, “Owning and Driving the Model T.” The first two pages offer a driver’s-eye view of the controls. There are three pedals: clutch, brake and reverse. Reverse? I had to find out what this was about.

From The Model T.

Now in a more receptive mood, I backtracked to chapter 2, “Creating the Model T,” which includes an explanation of the planetary transmission. It sounds simple enough to use, if a bit limited in ratios, and indeed, Ford chose it because it was easy to learn. In other respects, the Model T was quite innovative from an engineering standpoint (something I hadn’t really appreciated, despite having on many occasions visited the Henry Ford Museum, where Casey is curator of transportation). It was the first American car with a cylinder block cast in one piece, and it was one of only two American makes at the time with a removable cylinder head. This facilitated valve grinding, which was a part of periodic maintenance.

The T was also a sprightly performer. At 1,200 pounds, it was nearly 400 pounds lighter than its closest four-passenger competitor, the Buick Model 10 Tourabout. Moreover, that lightness translated to an intentionally flexible chassis, which allowed the car to take on terrain where others couldn’t venture (as shown above). Unlike my mother, I’ve never driven a Model T, but I’m richer now for knowing a bit about what it was like to do so.—David Schoonmaker

AMERICAN PESTS: The Losing War on Insects from Colonial Times to DDT. James E. McWilliams. Columbia University Press, $24.95.

An unfamiliar horde of hungry insects greeted the first Europeans to settle on American soil. With cash crops on their minds, the settlers responded by unleashing a haphazard assortment of sprays, lures and rituals. One farmer’s response to an infestation of caterpillars was to “take lighted charcoal in a chafing dish, and throw thereon some pinches of brimstone powder,” then set the dish beneath the affected tree. Others poured boiling water on their gardens before planting or used sheepskins to lure weevils away from stored grain.

These and other colorful remedies fill the first (and finest) chapters of James E. McWilliams’s American Pests. McWilliams shows that since colonial times, whenever farmers and entomologists have learned to control pests in a particular agricultural context, that context has changed and expanded. Typically there is a shift to a more expansive monoculture crop that fosters more drastic infestation and invites more desperate chemical countermeasures. The arms race against insects entered into by those European settlers is still escalating today.

The single most important “wrong turn” taken in the United States, writes McWilliams, was the “consolidation of authority over environmental issues in the hands of a relatively few powerful decision makers”—a move that “weakened the flexibility and ingenuity of biological and cultural methods of insect management.” He pleads for a return to a more personalized, democratic and locally adapted approach to pest control.

The book is peopled with strong and intriguing characters, from the farmers who experimented with brimstone and boiling water to the first professional entomologists and, finally, Rachel Carson. But especially for actions taken since about 1940, McWilliams increasingly assigns ulterior motives, intentions and agendas to entomologists, the government and chemical companies. Unfortunately, he often does so without providing the concrete evidence that would convincingly substantiate his claims.—Elsa Youngsteadt

FLOTSAMETRICS AND THE FLOATING WORLD: How One Man’s Obsession with Runaway Sneakers and Rubber Ducks Revolutionized Ocean Science. Curtis Ebbesmeyer and Eric Scigliano. Collins, $26.99.

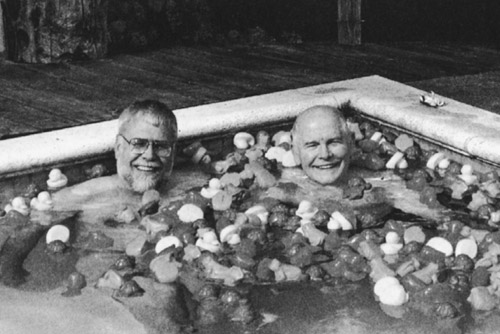

In May 1990, a storm swept 21 shipping containers from a cargo vessel and left 61,820 Nike shoes bobbing in the North Pacific. When they began appearing on North American shores eight months later, ocean scientist Curtis Ebbesmeyer (below [left], with colleague Jim Ingraham) saw an opportunity: He formed a network of beachcombers and used their reports as a way to track ocean currents.

From Flotsametrics and the Floating World.

Ebbesmeyer had begun his career as a conventional oceanographer, studying icebergs and oil spills, but his new study of “flotsametrics” grew into a full-time occupation. In January 1992, 28,800 bathtub toys went overboard near the international date line. In December 1994, 34,300 hockey gloves fell into the mid-Pacific. In each case, Ebbesmeyer’s simulations predicted when and where they’d come ashore, and his army of volunteers confirmed the accuracy of the predictions.

Ebbesmeyer writes with disarming enthusiasm, telling romantic stories of floating coffins, derelict ships and messages in bottles. But it’s clear that he’s a dedicated scientist, and his passion and resourcefulness reveal a true love of the sea. He doesn’t hide his dismay when describing Hawaii’s litter-strewn “Junk Beach” or the Great Eastern Garbage Patch, a broth of Pacific debris half the size of the United States. Reading his book, it’s hard not to be both captivated by the oceans and appalled at what we’re doing to them.—Greg Ross

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.