This Article From Issue

September-October 2008

Volume 96, Number 5

Page 435

DOI: 10.1511/2008.74.435

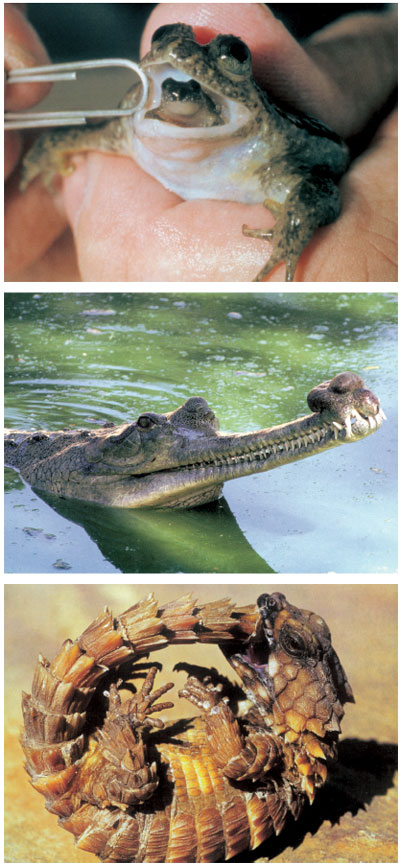

Even a person normally immune to the charms of amphibians and reptiles will soon be drawn in by the fascinating color photographs of Life in Cold Blood, the latest book by broadcaster and naturalist David Attenborough (Princeton University Press, $29.95). Beautiful or bizarre creatures grace nearly every page, and if you begin flipping through the book you'll be brought up short repeatedly—perhaps by the goliath frog as large as the small boy holding him in equatorial Africa, or by the saltwater crocodile thrashing the kangaroo in its jaws in the water. And what's this? A snake sailing through the air against a background of empty blue sky! Compelled to start reading, you discover that it's a paradise tree snake, which can launch itself from a branch, flattening its body to trap air beneath it, and glide 30 yards forward, steering as it goes. Then you spot a Komodo dragon strolling on a beach, its long tongue extended to sniff for carrion. The next thing you know, you're shoving the book under your friends' noses, insisting that they have a look.

From Life in Cold Blood.

When you settle down to read the text from start to finish, you realize that Attenborough is using creatures who are alive today to help readers visualize developments in the evolutionary history of these two classes of vertebrates, and to show diversification of forms. What might the first creature to make the transition from water to land 375 million years ago have looked like, for instance? Some combination of the lungfish and the Japanese giant salamander, perhaps.

The book goes on to cover the adaptations that were needed to allow amphibians to live on drier land (impermeable skin and shelled eggs). Then tortoises and crocodiles are introduced, two groups of reptiles that have changed very little over the eons. Chapters follow on lizards, leglessness (snakes and their burrowing ancestors) and cold-bloodedness.

Attenborough calls attention to the fragility of amphibians—their permeable skin leaves them unusually vulnerable to pollutants, and frogs and toads all over the world are becoming extinct. Reptiles, though, may benefit from global warming, which should allow them to extend their range at a time when mammals will be having difficulty finding food. They'll get along without us very well. —Flora Taylor

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.