Short takes on three books

By Fenella Saunders, Anna Lena Phillips, Emily Buehler

Storming the Gates of Paradise • Crime Scene Chemistry for the Armchair Sleuth • Banana

Storming the Gates of Paradise • Crime Scene Chemistry for the Armchair Sleuth • Banana

DOI: 10.1511/2008.74.436

STORMING THE GATES OF PARADISE: Landscapes for Politics. Rebecca Solnit. University of California Press, $24.95 cloth, $16.95 paper.

Rebecca Solnit has made it her work to assemble and reassemble the best ideas of the environmental movement, feminism and American visual art. Her writing, which considers both rural and urban landscapes, is rooted in the American West, particularly California and Nevada. Storming the Gates of Paradise, a collection of 35 of her essays, demonstrates her powerful and integrative thinking.

Solnit excels at deep exploration of her subjects. In "Excavating the Sky," she places the history of science in the context of Western culture, taking us from a meditation on the sky/land boundary in Western landscape painting to Galileo's telescopes and their role in advancing longitude calculation, which allowed greater European exploration and exploitation of what is now the American West.

From STORMING THE GATES OF PARADISE: Landscapes for Politics.

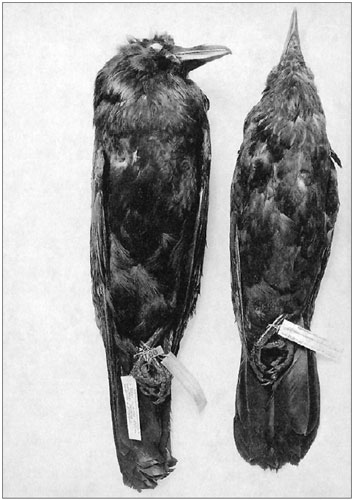

Each of the book's nine sets of essays has a striking photograph as its frontispiece. The image at right ("Ravens, Field Museum, Wyoming, 1871; Oklahoma, 1964," by Terry Evans) precedes the section titled "Infernal Museums," which includes, among other things, a piercing critique of the art museum being created in Bentonville, Arkansas, by Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton.

The essay "Other Daughters, Other American Revolutions" contextualizes the work of Rachel Carson, Betty Friedan and Jane Jacobs. Here Solnit illuminates the relationships between ecosystems, human-made spaces, human rights, environmental concerns and creative work. With wit and subtlety, she tackles the perceived and culturally reinforced separation between landscape and culture, which, she says, "makes politics dreary and landscape trivial." Her work offers revealing, sometimes even thrilling, alternatives to this glum view. —Anna Lena Phillips

CRIME SCENE CHEMISTRY FOR THE ARMCHAIR SLEUTH. Cathy Cobb, Monty L. Fetterolf and Jack G. Goldsmith. Illustrations by Linda Muse. Prometheus Books, $26.

Crime Scene Chemistry for the Armchair Sleuth explores dozens of aspects of forensic science, relating each one to a facet of chemistry. Every chapter is prefaced by a simple hands-on experiment, which adult readers can do at home with (supposedly) common materials, illustrating a crime-solving technique involving chemistry. Next, the chapter itself opens with a vignette laying out a crime-scene investigation. The reader is left to ponder "whodunit" while the pertinent chemistry is discussed, and finally, the detective on duty solves the case.

The topics covered progress in difficulty and include atomic and molecular structure, phases of matter, intermolecular forces and chemical reactions. The latter half of the book uses the chemistry discussed previously to analyze trace evidence—as when infrared spectroscopy is used to match bits of blue fiber found in the mouths of dead dogs to the ripped blue jeans of their killer.

The book, which assumes no prior knowledge of chemistry, is well organized, sprinkled with interesting analogies and written in inviting, understandable language. But some of the explanations are overly vague, and the authors have overlooked many opportunities for providing helpful diagrams.

Although some of the cases in Crime Scene Chemistry for the Armchair Sleuth are on the level of Slylock Fox comics for kids, many are clever. Be warned, however: The book makes use of a steady stream of puns and plays on words, and every character has a corny name, such as I. C. Yoo or Candace B. Real.— Emily Buehler

BANANA: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. Dan Koeppel. Hudson Street Press, $23.95.

The banana we eat today, the Cavendish, is not as tasty as the Gros Michel variety that our grandparents enjoyed, says Dan Koeppel, author of Banana. But in the 1960s the Gros Michel succumbed to a blight called Panama disease. Cavendish plants were initially immune, but a more virulent strain of the fungus has emerged to threaten them. Researchers are now trying to develop a commercially viable banana that can resist the disease.

From BANANA: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World.

Koeppel details the fruit's natural and cultural history. In ancient translations of the Bible, he says, Eve was tempted in the Garden of Eden not by an apple but a banana—a more suggestive image. The plant may have been one of the first to be cultivated, but the fruit was not widely known until the 19th century, when brave but brutal banana barons figured out how to export the fruit in large quantities. The environment and the health of native workers suffered, but the industry's exploitativeness has largely been hidden from Americans by spin-doctoring, delivered by such jolly characters as Chiquita Banana (above).

Koeppel is clearly enthralled with his subject. Writing with ease and eloquence, he has packed a great deal of information into the book. Whether the story ends happily may depend on how adventurous consumers are in trying new varieties of banana. Koeppel's mouthwatering descriptions left me dying to taste them all. —Fenella Saunders

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.