This Article From Issue

September-October 2007

Volume 95, Number 5

Page 458

DOI: 10.1511/2007.67.458

Aldo Leopold's Odyssey: Rediscovering the Author of A Sand County Almanac. Julianne Lutz Newton. xviii + 483 pp. Island Press, 2006. $35.

In "Odyssey," an essay from his posthumously published masterpiece, A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold traced the fictive histories of two atoms, pulled from parent rock and sent into ecological circulation at two different moments in North American history. Atom X, coaxed from limestone into the world of nutrient flow by a burr oak root when Native Americans ruled the prairies, meandered along a complex path through a fine-functioning ecosystem before haltingly descending the watershed to the sea; by contrast, atom Y, born from bedrock into a settler land of wheat and cattle and corn, moved downstream much more rapidly before being lost to the muck of the ocean floor. These two journeys seem intended to illustrate a basic ecological lesson about interconnection and complexity. But in the hands of Julianne Lutz Newton, they become parables of Leopold's own intellectual journey and his contributions to ecological science.

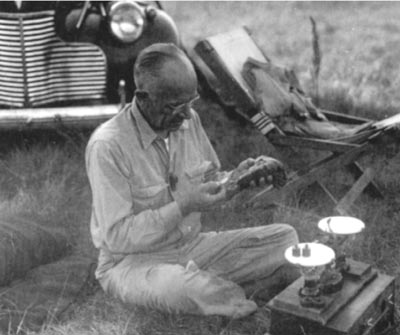

From Aldo Leopold’s Odyssey.

As Newton notes in her superb new book, Aldo Leopold's Odyssey, Leopold began his career as a forester, studying the world of atom Y and its ilk and striving to make short-circuited systems of resource production more efficient. But over the course of four decades, as he came to see the land as a complex biotic community, he argued that land managers needed to respect the goodness of atom X's inefficient, diverse journey. Indeed, he came to realize that the integrity, stability and beauty of natural systems should be measured not by how efficiently they produced wood fiber, game animals or crops, but by how diverse and attenuated were the paths of the atoms flowing through them. That journey from atom Y to atom X, according to Newton, was the essence of Aldo Leopold's odyssey.

I must admit to having picked up this book with some trepidation, for several good biographies of Leopold already exist, Curt Meine's Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work being the best among them. Moreover, Leopold's writings have been subjected to relentless scholarly exegeses; is there really a whole lot new to say about Leopold and his intellectual journey? The answer, it turns out, is yes.

Newton has managed to produce a study of refreshing originality by focusing on aspects of Leopold's odyssey that have received less attention, while all but ignoring the well-worn paths of previous Leopold scholarship. Moreover, she does this in an unassuming way. Hers is not an explicitly or aggressively revisionist study, but an innovative slice through Leopold's life. As Newton puts it in her preface, this is "not a full biography of Leopold; rather, it is an account of the maturation of his thinking," with a particular focus on his evolving interest in "land health."

Leopold was born and raised in the agricultural Midwest and returned there to play out his final decades, but he was also the product of an Eastern education and a Western apprenticeship. He was among the first generation of professional foresters trained in the United States, at the Yale School of Forestry. After receiving his master's degree there in 1909, he took a position with the fledgling U.S. Forest Service in the Southwest, helping to bring under administrative control the region's wild public-domain forestlands. There, in the years just after World War I, Leopold famously suggested that the Forest Service protect a large, roadless chunk of national forest as the Gila Wilderness, thereby inaugurating a new brand of nature preservation and a national wilderness movement.

But Newton does not focus her early chapters on Leopold's burgeoning wilderness appreciation, which has already been the subject of extensive scholarship. Instead, she insists that the more formative Southwestern episode for Leopold was his grappling with the puzzling historical relationship between grazing, fire and vegetational change in the region. Scholars have long recognized this aspect of Leopold's experience as important both to ecological studies of the Southwest and to the trajectory of Leopold's thinking, but no one else has given it the central place in his early career that Newton does. For the most part, she convinces in doing so.

Perhaps Newton's most important contribution is to take Leopold seriously as a scientist. It is a stock-in-trade assumption that he brought "ecological thinking" to American conservation, but too often scholars have failed to assess seriously what that meant in relation to the various branches of ecological science. As a result, we mostly know Leopold as a philosopher-activist who popularized ecological thinking as a prelude to modern environmentalism. As a useful corrective, Newton provides a detailed portrait of Leopold ensconced in the worlds of professional ecology and wildlife biology from 1924, when he moved to Wisconsin, until his untimely death in 1948. Just as important, she makes forceful arguments about his formative contributions to these fields. Leopold not only wrote a pioneering and influential textbook on wildlife management, but he also helped to invent the field (then known as game management), build it institutionally and link its applied goals to academic ecology.

Sometimes Newton's arguments for Leopold's scientific importance and originality can stretch a bit thin. Nonetheless, Newton does provide a full and fascinating portrait of Leopold as a scientist who struggled to keep the gap between the modern biological sciences and natural history bridged.

But Leopold was always more than a scientist, and he could be quite critical of the reductive and dispassionate ethos of modern science—a point that Newton well recognizes. Indeed, one of the striking aspects of Leopold's "Odyssey" essay—and by extension his entire career—was his capacity to make even the atomic level of things into tactile and legible natural history. As modern science taught people to distrust their senses and lodged scientific expertise in the hands of a small cadre of elite researchers, Leopold came to believe that environmental salvation must be democratic and that such salvation would come only if the aesthetic fruit of ecological science spread far from the professional tree. He was after nothing short of a revolution in perception.

In Newton's fine study, we get very little of Leopold as a wilderness prophet or as the embodiment of a biocentric ethical awakening. Instead, she gives us a portrait of a serious, disciplined and joyous ecological theorist, whose greatest desire was to speak plainly to farmers and other landowners so that they might come to have a passion for the land as deep as his. Illustrated by a series of beautiful photographs that Leopold himself took, Aldo Leopold's Odyssey is a welcome addition to our understanding of America's most important modern environmental thinker.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.