Seeing the "Sixth Sense"

By Robert Frederick

Live imaging of body-sensing neurons required both new techniques and new technology.

Live imaging of body-sensing neurons required both new techniques and new technology.

It takes a special set of nerve cells for us to know where our body parts are without looking at them. This propioceptive system is sometimes referred to as our “sixth sense,” and researchers had been limited in their understanding of how it works because they couldn’t see those sets of body-sensing neurons in action.

“We knew a lot about the development and the anatomy of these sensory neurons,” says Wes Grueber, a neurobiologist at Columbia University in New York City, “but we couldn’t know for sure how this could link to what they do for the animal.”

The animal of study, the fruit fly, is a model organism in biology generally, and research into many model organisms—including the adult fruit fly—had previously described how the propioceptive system works for rigid skeletons and joints. Grueber wanted to know how the propioceptive system works in fruit-fly larvae as a model for animals with flexible skeletons.

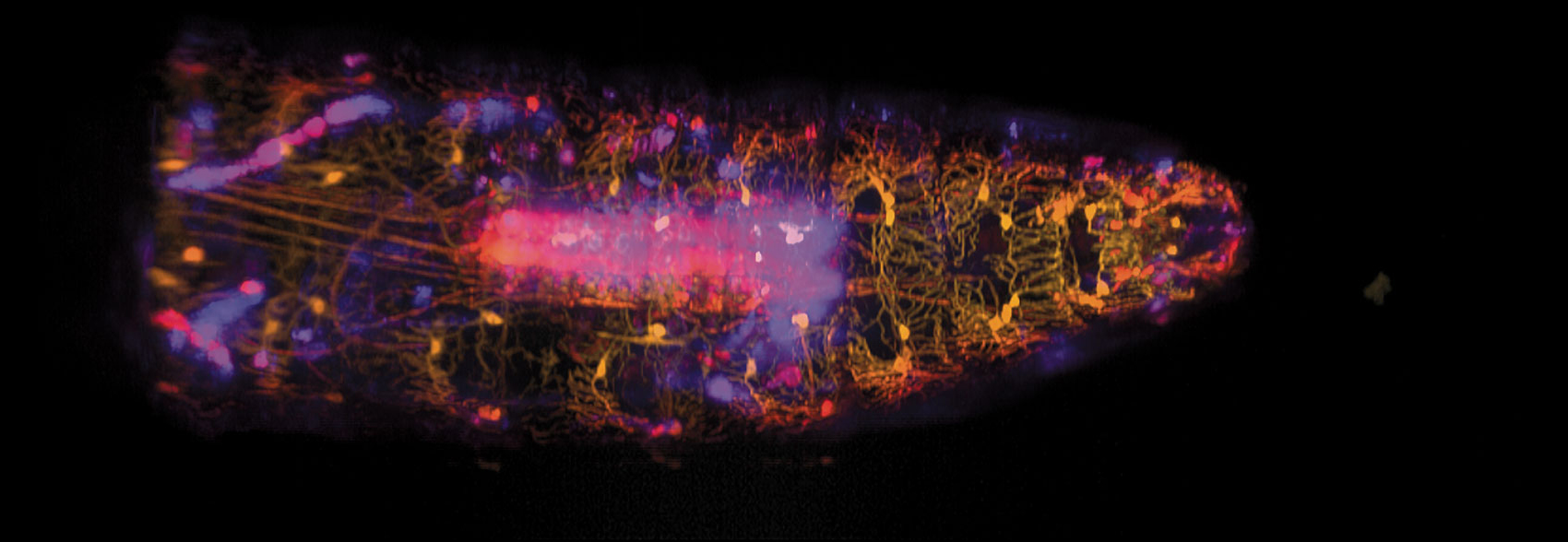

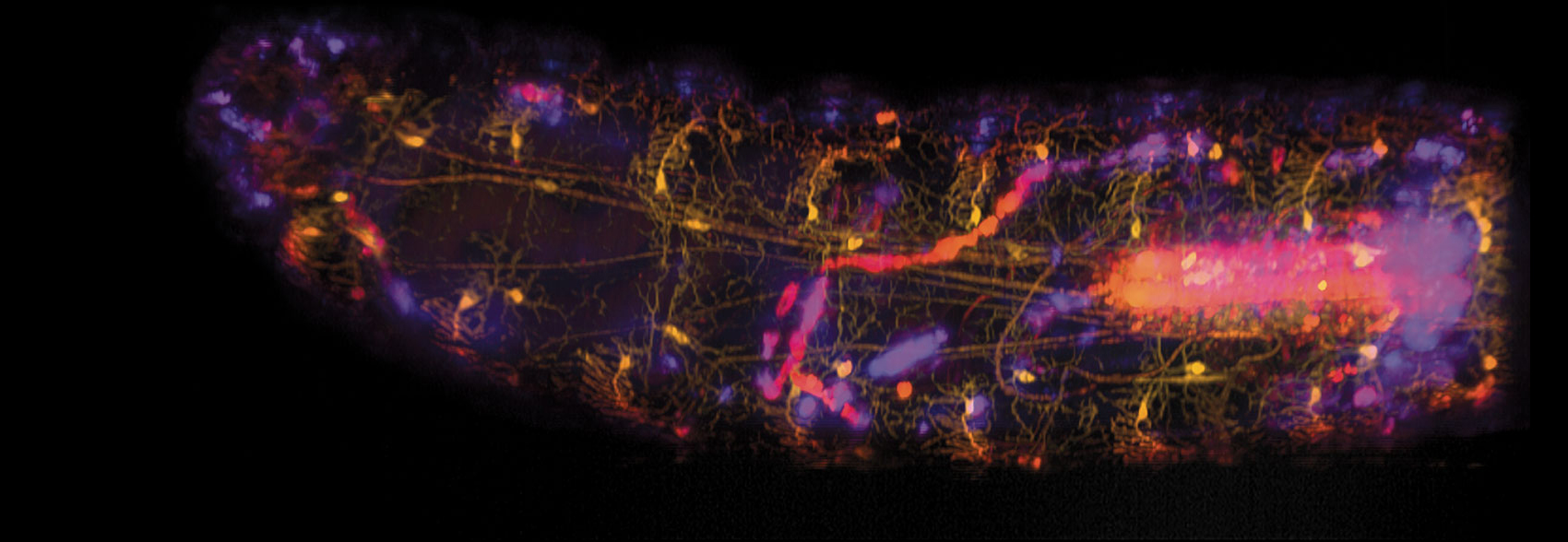

Wenze Li and Rebecca Vaadia / Hillman and Grueber labs / Columbia's Zuckerman

Technologically, the lessons learned could help to improve the soft, squishable robots that are being developed for a variety of tasks, including search-and-rescue missions. But the basic research may also inform the study of propioceptive dysfunction, which can affect every aspect of a person’s life, including the ability to speak.

Past research on the function of the larvae’s propioceptive system had led scientists to hypothesize that those sets of sensory neurons had redundant functions, at least in part. That’s because they found that the larvae exhibited similar behavior even when different subsets of their proprioceptive neurons were electrically silenced (and were thus unable to signal the brain). Previous direct studies of the electrophysiological activity of these sensory neurons had been carried out only in dissected specimens.

“So that’s why we linked up with Elizabeth Hillman, who helped us to perform the imaging of sensory neurons as they’re acting and as the animal is moving around in real time,” Grueber says.

Hillman, a physicist and engineer also at Columbia University, had developed SCAPE microscopy (for Swept, Confocally-Aligned Planar Excitation) for high-speed three-dimensional microscopy in living organisms. She licensed to Leica Microsystems in 2016, and she was recently recognized for her career accomplishments with the 2018 Biophotonics Technology Innovator Award from SPIE, the International Society for Optics and Photonics. But Grueber’s research drove the technology further. She says, “I really credit Wes with having challenged us to improve and drive the quality of the images that we were getting from the microscope to the point that they were actually of use to him as a biologist.”

Their combined effort, about which they published in the March 18 issue of Current Biology, included the doctoral thesis work for a couple of Hillman and Grueber’s coauthors along the way. On the biological side, Grueber’s team genetically altered fruit-fly larvae to express two different fluorescent proteins, red (tdTomato) and green (GFP), in the specific cells needed to be able both to track the movement of the larvae and to see when sensory neurons signaled the brain after they were activated by the moving, flexible skeleton. Hillman and her team’s technological improvements to SCAPE microscopy included adding the capacity to capture multiple colors while the larvae could move freely, or “groove,” as Hillman puts it, which meant capturing the larva’s movement at high speed.

“I like to say it is kind of the speed of life,” Hillman explains about the 10-volumes-per-second recording speed, which allows each frame of the resulting video to appear as if the larvae—the volume being scanned—is stationary and not blurry. Although Hillman says she has since been able to improve the speed to 100 volumes-per-second, 10 was sufficient to track individual cells from one frame to the next while imaging the whole creature with a field of view of more than 1 millimeter.

The resulting recording is built from an enormous amount of data, as a sheet of laser light swept back and forth through the moving larva’s body. The cells fluorescing red maintained consistent brightness, and the varying brightness of the green fluorescence provided information on calcium levels in the neuron cells—a proxy for understanding neuron activity. Without measuring the position and intensity of both colors simultaneously, Hillman says, it would have been very difficult to see exactly where the cells were and also avoid the “weird effects of movement that would be contaminating our signal.”

Wenze Li and Rebecca Vaadia / Hillman and Grueber labs / Columbia's Zuckerman

In addition to demonstrating new capabilities for SCAPE microscopy, the team reported new insights into the propioceptive system. One such insight was that each cell type has a unique—rather than a partially redundant—role.

“One initial surprise is that of a group of six neurons that we looked at, five—so all but one—were sensing some aspect of that forward contraction,” Grueber says, with the remaining neuron sensing the stretched phase of movement. It could be that those five neurons allow the larva to more precisely sense its forward contractions. That’s because each of the five neurons has a unique position, so each fires when the part of the flexible skeleton they are connected between compresses. But a better understanding of that action is part of what Grueber and his team are currently trying to tease out, by electrically silencing the neurons one by one and carefully measuring behavior.

With their overlapping interests, Hillman is looking forward to working with Grueber and other researchers studying the patterns of all of the neurons in entire organisms as those organisms sense both where their bodies are (using the propioceptive system) and the environments they are in, and then react.

“We’ve set the scene now for us to use this method in any number of these very small model organisms,” Hillman says, including the roundworm, C. elegans, and the developing brains and hearts of zebrafish larvae.

Listen to a podcast interview with the researchers:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.