This Article From Issue

May-June 2004

Volume 92, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2004.47.0

Greek Fire, Poison Arrows and Scorpion Bombs: Biological and Chemical Warfare in the Ancient World.

Adrienne Mayor.

319 pp. Overlook Duckworth, 2003. $27.95.

Saddam Hussein makes regular appearances in this colorful survey of the ways in which people have been killing one another by ingenious biochemical means ever since antiquity. He features primarily as a warning that biological and chemical weapons, once created, are almost impossible to contain and are liable to backfire against those who design and deploy them. This is the moral message of Adrienne Mayor's study, and it deserves our wholehearted agreement, even if recent events have shown that Saddam was not such a good example to have picked after all.

Mayor's other message is that biochemical warfare is not a modern invention but was practiced thousands of years ago, and that even then its dangers were recognized and were immortalized in myth. She is absolutely right to stress that ancient warfare was not the ritualized affair imagined by many scholars—not least the leading ancient historian Josiah Ober, who happens to be her husband—and that techniques of destruction were among the most highly developed elements of ancient technology. Two chapters on the military use of snake venom and plant toxins as poisons make a strong case for its significance in ancient warfare. Included, for example, are intriguing ideas about the Scythians of the Russian steppes painting their arrows in snakeskin patterns and dipping them into vials of poison attached to their belts. The concluding chapter on the application of fire, culminating in the hellish Greek Fire, which was much like napalm delivered by massive flame-throwers, is also impressive, although it must be admitted that petroleum-based incendiaries were relatively rare in the ancient world and gained real prominence only in Byzantine and Islamic warfare.

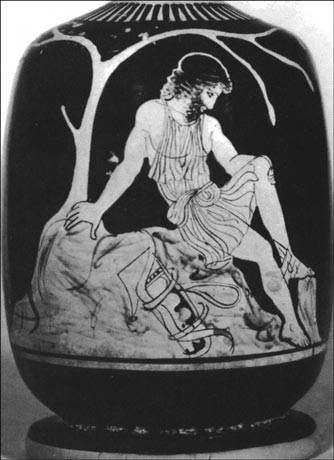

From Greek Fire.

Elsewhere in the book, the search for biochemical weapons is sometimes too broad and uncritical. I am not sure whether war-elephants really count as a form of "manipulation of the forces or elements of nature to insidiously attack or destroy an adversary's biological functions in ways that cannot be deflected or avoided," or, if they do, why cavalry does not also qualify. Nor am I convinced that the evidence for many of the imaginative food- and animal-based tricks cited will stand up to scrutiny. A large number are attested only in anthologies of stratagems compiled in the first and second centuries A.D., and at least some are almost certainly late inventions attributed to famous figures from the past. To say of one such story, which features a woman tricking the enemy into eating poisoned meat, that it "is very old, dating to about 1000 B.C.," is therefore misleading. Worse is the attribution of several farfetched biochemical wheezes to Alexander the Great on the strength of the Alexander Romance, which, as the name suggests, is a medieval fiction, with about as much historical content as the average Arthurian romance.

The most sensational part of the book is without a doubt the middle chapter, "A Casket of Plague in the Temple of Babylon," which argues that some temples in the ancient world stored "lethal biological material that could be weaponized in times of crisis." This is based on stories that "plague demons" were contained in some temples, most famously in the Ark of the Covenant in the Temple at Jerusalem, from which infectious agents were inadvertently released by trespassers, who thereby caused disastrous epidemics. By assuming, for example, that the Ark may have contained a piece of cloth that "harbored aerosolized plague germs, or an insect vector," Mayor is able to rationalize these tales to spectacular effect as she conjures up an image of priests using their temples as "laboratories for experiments with poisons and antidotes, with diseases and even primitive vaccines," all with a view to engaging in "biological sabotage." Spielberg must be kicking himself for missing a trick in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Unfortunately, as is revealed only in the final sentence of a long endnote, it was not until nine years after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by Titus that plague broke out, so the theory comes crashing down in this case. The evidence for biohazardous temples in Babylon and Greece is no better. There is of course a simple, prosaic explanation for the link between temples and plagues: Epidemics were widely thought to be sent by gods and were believed to be suitable punishment for acts of sacrilege such as tampering with temple treasures.

Greek Fire should be handled with care, then, and readers may have their fingers burnt if they do not retain their critical distance. Nonetheless, it is an undeniably fascinating and engaging book which, more often than not, contributes usefully to the history of both early science and ancient warfare.—Hans van Wees, History, University College London

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.