This Article From Issue

May-June 2003

Volume 91, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2003.44.0

Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion. Feng-hsiung Hsu. xviii + 298 pp. Princeton University Press, 2002. $27.95.

Deep Blue: An Artificial Intelligence Milestone. Monty Newborn. xvi + 346 pp. Springer-Verlag, 2003. $34.95.

In the early 1870s, or so the legend goes, John Henry battled the steam drill in a competition to see who was better at driving steel: man or machine. Man won, but victory was short-lived—John Henry soon died from the physical ordeal of the contest. With more than a century of hindsight, we can look back amusedly at this and many other attempts by humankind to preserve its vanity and sense of superiority.

Today we accept that machines can be physically superior to humans: No one would seriously consider competing with a forklift in a weight-lifting competition. But when it comes to intelligence, how do we stack up against machines? Investigators in the field of artificial intelligence are attempting to create the computer equivalent of human cognitive abilities. Research over a period of roughly 50 years has produced numerous successes. For example, we take computerized spelling and grammar checkers for granted; they are standard components of all word processors today. But imagine how people in John Henry's day would have reacted to a demonstration in which a machine corrected errors in spelling and grammar!

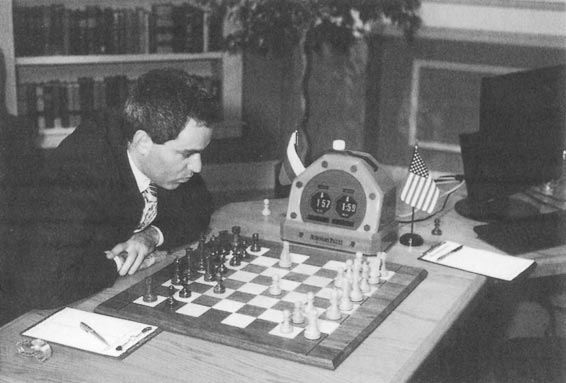

From Deep Blue

One of the early "grand challenges" in artificial intelligence was to build a chess program capable of defeating the best human players. The research community, underestimating the incredible abilities of the human brain, seriously misjudged how difficult the task would be. The challenge was finally met in 1997, when in a six-game exhibition match the chess machine Deep Blue defeated reigning World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov with two wins, one loss and three draws. A milestone in the creation of machine intelligence had been achieved.

Given the scientific importance of the accomplishment, there have been surprisingly few attempts to properly document it. Most of the books about the match have been analyses of the games' chess moves. But two recent books provide a more in-depth look at Deep Blue's development.

Behind Deep Blue is an account of the project by Feng-hsiung Hsu, the system architect and chip designer for the machine. In a 1982 paper, Joseph Condon and Ken Thompson, who together created the hardware and software for the chess machine Belle, showed a strong correlation between Belle's speed and performance. Thus, in theory, to beat the best humans all one had to do was create a very fast chess machine. Hsu and the Deep Blue team did just that. Building on the work of Condon and Thompson, they made a computer chip that could analyze several million chess positions per second (humans typically search only one or two positions per second). Deep Blue used 500 of the chips at once. Poor Garry Kasparov!

Hsu's book tells the story of his personal quest to defeat Kasparov, who had become World Chess Champion in 1985 at the age of 22. Over the span of a dozen years we see Hsu's initial idea for a chess machine that could best the World Champion evolve through several stages of program development, including feasibility testing (ChipTest), early success (Deep Thought), mixed results (Deep Thought II), strong grandmaster level of play (the debut version of Deep Blue, which lost a match with Kasparov in 1996 by a score of 4 to 2), and finally victory (the retooled, smarter, faster Deep Blue that won the 1997 rematch).

Hsu emphasizes the parts of the story he was closest to, including the evolution of the chess chip. He shows the reality of scientific exploration, warts and all, chronicling the obsessiveness, competitiveness and costly mistakes that mark most research (along with, of course, the thrills, fun and camaraderie). Yet he still manages to come across as endearing, though all too human, in this vivid, intimate portrayal of personal toil and triumph. Behind Deep Blue is warm, humorous and insightful.

Monty Newborn, the author of Deep Blue: An Artificial Intelligence Milestone, has long been involved in computer chess and was instrumental in making possible the 1996 and 1997 matches between Deep Blue and Kasparov. His book documents the external events—what happened where and when—and deliberately avoids getting into details of the technology. This is the book's greatest strength—and its greatest weakness. It is accessible to anyone; little background knowledge is needed to enjoy the story. But the lack of technical detail creates a strange gap: As Deep Blue goes from event to event, its performance gets slowly better, but the reader doesn't learn why results are improving. Details about what has changed in the program to cause this are omitted. Without any discussion of the daunting tasks involved in building Deep Blue—designing and testing its hardware and software, incorporating chess knowledge—it is hard for the reader to appreciate the effort required.

Whereas Newborn avoids discussing hardware and software issues altogether, Hsu emphasizes the hardware design issues he knows so well, while giving little attention to the software challenges. Yet the software aspects of this project are much more interesting: What chess knowledge should the program incorporate? How does it evaluate chess positions and choose moves? How can mistakes made by the program be recognized and fixed? Regrettably, neither book has much discussion of the huge efforts of team members (principally Murray Campbell and Joe Hoane) to address such questions.

The books complement each other nicely. Newman's book meticulously documents the historical record. Hsu's book goes behind the scenes to adorn the bare facts with anecdotes and insights, reminding us that behind every major technological advance is a group of dedicated people with brilliant ideas and a commitment to success.

Kasparov was shocked by his 1997 loss and clamored for a rematch. Sadly, IBM retired Deep Blue and ended the project (the machine is now at the Smithsonian). Science had one data point that suggested machines might be better than humans in chess. But science is all about reproducible results.

In October 2002, the No. 2 player in the world, grand master Vladimir Kramnik, played an eight-game match with the program Deep Fritz (no relation to Deep Blue), which ended in a tie. In January and February 2003, Kasparov returned to battle Deep Junior (another program unrelated to Deep Blue). The result? Another tied match. The evidence to date strongly suggests that the best chess programs can stand up to the best humans.

A century from now, Kasparov may well be regarded in the same light as John Henry. Computers will improve year by year through new research and better technology, while human players like Kasparov will only get older, an inherent weakness in the human architecture for intelligence. The challenge to human intelligence from artificial intelligence has only just begun.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.