This Article From Issue

March-April 1999

Volume 87, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/1999.20.0

Native American Ethnobotany. Daniel E. Moerman. 927 pp. Timber Press, 1998. $79.95.

Medicinal Plants of the World: Chemical Constituents, Traditional and Modern Medicinal Uses. Ivan A. Ross. 425 pages. Humana Press, 1999. $99.50.

The ethnobotanical community has recently been witness to a spate of new, comprehensive works, but these books vary greatly in purpose and audience. For example, in 1996 Andrew Chevallier gave us The Encyclopedia of Medicinal Plants, a stunning color album suitable for the coffee table yet academically sound. The two books under consideration here are both very different not only from Chevallier's but also from one another.

Daniel Moerman's massive work, long anticipated by ethnobiologists and anthropologists, is striking. A quarter-century in development, it considers 44,691 uses for the 4,029 plants he discusses. Its pages are brimming with the most complete explication of Native Americans (from Alaska to the Mexican border; none from Central and South America) and their interaction with plants ever undertaken—and, thankfully, completed. Half of the uses listed are medicinal, but Moerman also considers foods, fibers, fertilizers and fuels. Not left out are plants used as incense, insecticides, instruments, soap, snuff and for smoking. The list goes on. Moerman shares his personal history about how this work came together and provides tabular information probably impossible to find anywhere else—nothing to date has been so thorough and systematic. For instance, he lists the 10 most used plants by North American native peoples. (Number one is the western red cedar [Thuja plicata] with 368 uses, 52 as drugs and 188 as fiber alone.)

An anthropologist by training (obviously his botany did not go untutored!), Moerman is sensitive to issues not often considered in ethnobotanical works. To wit: "The name Eskimo . . . is, apparently, an English mispronunciation of a French mispronunciation of a Montagnais or Micmac word ayashkimew, which seems to have meant something like 'eaters of raw meat.'" He goes on to point out that he has used names of peoples as used in his original reference sources, and so several names for the same peoples are necessary (requiring cross-listing). Some 291 ethnic groups are to be found in Native American Ethnobotany, from Abnaki to Zuni.

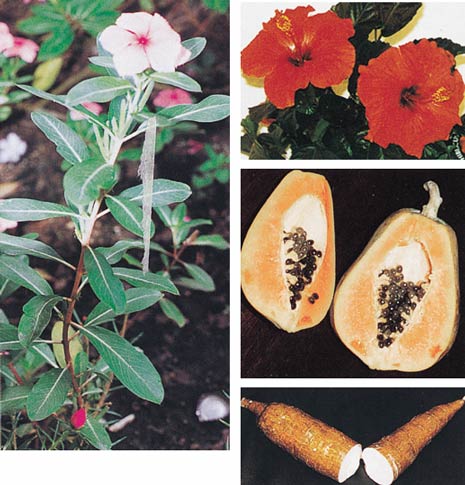

From Medicinal Plants of the World.

His botany is admirable and fully modern: He lists, for instance, "Lamiaceae (Labiatae)," instead of maintaining the old family names as standard. The heart of the work is, of course, the plant list and use discussion in the "Catalog of Plants," running nearly 600 pages. A typical entry might be exemplified by "Cucumis, Cucurbitaceae. Cucumis melo L., Cantaloupe. Food—Hopi: Dried food: Rind removed, meat pressed flat or stripped, wrapped into bundles ... Iroquois: Bread and Cake: Fresh or dried flesh boiled" and so on. This is clearly dense—not a good evening's read. It is unrelentingly a reference book and should be used as such, with notes, bibliography (astonishingly short with but 206 entries) and several indices of great value (tribes, uses, synonyms, common names).

Most regrettably, however, there is not a single illustration in the entire book. The cost (miraculously low for this masterpiece) would likely have been prohibitive had photographs or drawings been added, but not having them is most disappointing.

Ivan Ross's Medicinal Plants of the World, like Chevallier's volume, is selective, but it is far from being attractive enough for the coffee table. Ross's purpose is to discuss the chemical constituents and the traditional and modern medicinal uses of the highly eclectic list of species. Each chapter is a different plant, but a chapter is not a smooth-flowing discussion of the plant and its properties. Rather it is a listing of fundamental features of the chosen plant. Starting with a listing of common names worldwide (Allium sativum, garlic, is ta-suan in China and lai in Nicaragua, for instance), Ross follows a formula that includes such section headers as "Botanical Description," "Origin and Distribution," "Traditional Medical Uses" and so forth. These can be frustratingly short (20 words for garlic's origin and distribution) and shy on details (the garlic in England: "Hot water extract of dried bulb is taken orally for diabetes").

But the bibliography entries are extensive, running 68 pages, and elaborately constructed in the text. The chapter lengths vary greatly (40 pages for the garlic; nine for Hibiscus). Although this possibly reflects our knowledge of each plant or the breadth of its uses, it leaves open why and how the 26 species (in 26 chapters) were chosen. One of the most intriguing sections in each chapter is the list of "Chemical Constituents," but it is also one of the most frustrating, utterly lacking references—a severe omission. The modern pharmacology sections are useful though brief in most.

Typographical errors make one a bit leery of the editorial guardianship of the more complex information elsewhere in the text. Although there are a few color plates, black-and-white chapter-header pictures are muddy and some unrecognizable (Hibiscus is a black blob). Despite these shortcomings, this book should be on every library shelf of universities and colleges, industries and other institutions where ethnobotany, pharmacy and plant chemistry are of concern. It is, however, very expensive for the personal library of all but the most ardent ethnobotanist.

Two new works, two differing approaches, two visions of what science needs; but both have a very special value. No library can be without either, and no specialist can do without consulting them, especially Moerman's offering. His work will likely never be surpassed. A dangerous prediction? Not likely. This is probably the magnum opus of the field. We are all indebted to him for this marvelous achievement.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.