This Article From Issue

May-June 2006

Volume 94, Number 3

Page 272

DOI: 10.1511/2006.59.272

The Plausibility of Life: Resolving Darwin's Dilemma. Marc W. Kirschner and John C. Gerhart. xvi + 314 pp. Yale University Press, 2005. $30.

Is life plausible? Well, it's more than plausible, it has actually happened! What we need to ask, rather, is whether our explanations for how life came about and diversified are plausible. So the title of Marc W. Kirschner and John C. Gerhart's book implies the wrong question. Despite that, The Plausibility of Life makes for informative and enjoyable reading, and the issues the authors raise are worthy of attention.

The book takes as its starting point the position that the currently accepted version of evolutionary theory, the so-called Modern Synthesis, although not wrong, is incomplete. Similar rumors have been circulated in other recent books, including Mary Jane West-Eberhard's Developmental Plasticity and Evolution, Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb's Evolution in Four Dimensions, and Phenotypic Evolution, a book by Carl Schlichting and myself. But those rumors have been strenuously denied by researchers who have situated their careers squarely within the Synthesis, which came of age in the 1930s and 1940s.

The two key questions concerning The Plausibility of Life, then, are, Do we actually need to add more components to the structure of evolutionary theory? And if so, is Kirschner and Gerhart's book the contribution some of us have sought for years? The answer to the first question is a definite "yes," and to the second one, a qualified "partially so." Let me explain.

The Modern Synthesis itself built on Darwin's two major realizations: first, that all living organisms are related to one another by common descent; second, that a primary explanation for the pattern of diversity of life—and especially for the obvious "fit" of organisms to their environments—is the process that he called natural selection. It took about seven decades for biologists to add the next round of important building blocks to the Darwinian view of life. Modern Synthesists such as Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr, George Gaylord Simpson and G. Ledyard Stebbins reconciled disparate fields of biology, from population genetics to paleontology, by expanding the array of evolutionary processes to include migration, mutations, assortative (nonrandom) mating and (random) genetic drift.

What the Modern Synthesis glaringly left out was the field of developmental biology and its subdiscipline, embryology, which wandered almost on their own for a few additional decades, until "evo-devo" (evolutionary developmental biology) came into vogue in the 1990s. The incompleteness of the Synthesis consisted not only in leaving out that entire area of research (which would be bad enough) but also in failing to address (or worse, sweeping under the carpet) important questions, chief among them the problem of the origin of so-called evolutionary novelties.

Evolutionary novelties are those (usually) complex structures that allow the organisms that evolve them to exploit new aspects of their environment or to adapt to new niches, often in a spectacularly successful fashion. They also happen to be the sort of thing Darwin struggled with most in On the Origin of Species: eyes, wings, hearts and brains. Not coincidentally, the difficulty of evolving such complex biological structures has also fueled evolution deniers, from the Reverend William Paley (whose "watch found on the heath" argument evoked an extensive response from Darwin) to the modern supporters of so-called "intelligent design."

Now, it has never been clear to me why the existence of natural phenomena that are at the moment difficult to explain seems to fuel both the reaction that "there is a fundamental flaw in the theory" (intelligent design) and the opposite response that "there is nothing wrong, everything has been explained" (the Modern Synthesis). Science, by its very nature, deals with things for which we lack explanations—things that might otherwise compel us to turn to supernatural notions. By the same token, if evolutionary biologists really had already explained everything, what on earth would justify my job as an active researcher?

Assuming, then, that there really are problems that have not been satisfactorily solved within the Modern Synthesis, do Kirschner and Gerhart provide us with answers? Well, first of all, the book is aimed at a general audience. Thus it is hard to evaluate it as an original contribution to science, because many of the arguments are not sufficiently developed or are not substantiated by a thorough analysis of the literature. This is an interesting trend that seems to have taken hold in recent years (Evolution in Four Dimensions is another example), and it is hard to know what to make of it. On the one hand, we are witnessing a welcome return to the idea that cutting-edge science is for everybody. Darwin's On the Origin of Species, after all, sold out on its first day and was purchased by laypeople as well as academics (of which there were few at the time anyway). On the other hand, with trade books one can get away with speculations and generalizations that would be harder to pass through the rigorous process of peer review that technical books usually undergo.

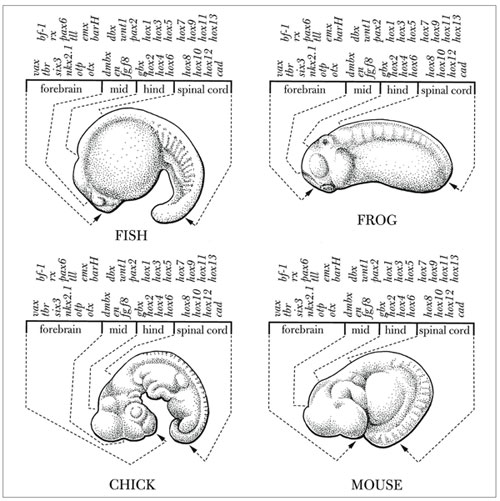

Be that as it may, Kirschner and Gerhart's main idea is that the missing piece in the edifice of the Modern Synthesis is what they call "facilitated variation." The basic idea is sound: Organisms are not analogous to human-engineered machines (contrary to what creationists and proponents of intelligent design keep insisting); rather, they are characterized by developmental systems that are capable of accommodating quite a bit of disruption—be that from changes in the external environment (phenotypic plasticity) or from mutations in their genetic makeup (genetic homeostasis). This ability to accommodate is in turn made possible by the modular structure of the genetic-developmental system itself, which allows organisms to evolve new phenotypes by rearranging existing components. A splendid example of this evolutionary and developmental flexibility is provided by the homeobox genes that preside over the spatial differentiation of embryos, from fruit flies to humans.

From The Plausibility of Life.

Facilitated variation is indeed one of the empirical as well as conceptual developments that have marked evolutionary biology during the past decade or so. However, it is not the stunningly new insight that Kirschner and Gerhart imply it to be. Plenty of other authors have talked about concepts such as the modularity of organisms, genetic and developmental homeostasis, evolution by alteration of regulatory sequences, and even evolution as a continuous process of "tinkering" with preexisting elements (as opposed to creating new complex characters from scratch)—an idea put forth by François Jacob as long ago as 1977. Kirschner and Gerhart's effort is a valuable update of some of these ideas, but it hardly constitutes "a new theory" to complement the Modern Synthesis.

Kirschner and Gerhart also peculiarly ignore or downplay at least two other major pieces of the evolutionary puzzle that have been brought forth recently as crucial to the development of a new synthesis. One is the inherent capacity of organisms to accommodate phenotypic plasticity—environmentally or genetically induced changes. Plasticity has been studied for more than a century, but it has come of age in the past two decades as a central characteristic of living organisms, one that has been implicated in speciation, adaptation and the origin of phenotypic novelties. Although Kirschner and Gerhart do mention phenotypic plasticity, they confine it to a secondary role (the term doesn't even make it into the index). They apparently do not realize that it is a crucial component of what they call facilitated variation.

The second crucial piece, entirely missing from The Plausibility of Life, is the (very) recent resurgence of the concept of inherited epigenetic variation. A significant amount of empirical research and at least one book tackling its conceptual implications (Evolution in Four Dimensions) are forcing biologists to face the existence of several layers of heritable variation above and beyond the classical genetic one. Inherited epigenetic variants can interact with their genetic counterparts to multiply by orders of magnitude the phenotypic variation available to natural selection, thereby expanding the mechanistic bases of evolutionary theoretical explanations and greatly increasing their plausibility as an account of life's diversity.

The Plausibility of Life ends with a brief critique of intelligent design, suggesting that the concept of facilitated variation will provide a solid argument to rebut creationists. I applaud the authors' intention, as it seems to me that more scientists ought to face the realities of public misunderstanding of science. But their presentation is too brief, and a bit too simplistic. The "controversy" about evolution has nothing to do with the soundness of scientific explanations of the history of life: It's not a scientific controversy, but a social, cultural and political one. Creationism is the result of centuries of anti-intellectualism in the United States, coupled with sometimes cynical exploitation of the issue for political gain. In addition, many scientists have no interest in getting out of the ivory tower to talk to the very same public that pays their salaries and funds their precious research grants. The recent defeat of intelligent design at the trial in Dover, Pennsylvania—at the hand of a conservative judge appointed by George W. Bush—will do much more to promote sanity in public education than any theory about facilitated variation, as scientifically sound as the latter may be.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.