This Article From Issue

March-April 2009

Volume 97, Number 2

Page 167

DOI: 10.1511/2009.77.167

LOST LAND OF THE DODO: An Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion, and Rodrigues. Anthony Cheke and Julian Hume. 464 pp. Yale University Press, 2008. $55.

Oceanic island chains built by volcanic activity are initially lifeless—dark spots on a lighter sea. But no matter how remote their location, eventually they are colonized. A bird flies in, bringing seeds in its gut or caught in its feathers. Other seeds arrive borne by wind or water. A lizard floats in on driftwood. A seal hauls itself onto the shore. Forests emerge and the islands slowly change color from gray-black to green.

On hundreds of islands, landscapes of rock have come to life in this fashion. The particular trajectories of the biota on any island depend on which species arrived first. In each set of islands, different lineages prosper. The radiation of species is happenstance, following Darwin’s rules, with an infinite variety of possible ends.

When humans arrive on islands, new trajectories ensue (most of them unfortunate). Easter Island was once a subtropical island forested with a variety of tree species, including many palms. When humans first discovered the island remains a subject of debate, with estimates ranging from A.D. 300 to 1200 Yet by the time Europeans arrived in 1722, many of the island’s native species, including nearly all the trees, were apparently extinct. Visitors now find a land of grassy hillsides punctuated by the island’s famous stone heads.

The Galápagos Islands were not discovered until the 16th century. Early visitors included whalers and hunters, who diminished the populations of seals and tortoises but left much of the island life largely unaffected. When Darwin arrived in 1835, the islands were still home to nearly the full variety of endemic species that would have been seen thousands of years earlier. It was in these species that Darwin would, some years later, discern the mechanics of natural selection. In the beaks of finches and mockingbirds, he found the evolutionary consequences of competition for scarce resources. Today, along with salt-spitting marine iguanas and near-tame sea lions, one can still find 29 species of birds (22 of them endemic to the Galápagos), including flightless anhingas and wild hawks unafraid to alight on a visitor’s head. The future of this wonderland is tenuous; invasive species have wreaked havoc on some of the islands, and humans (particularly those engaged in commercial fishing) have done additional damage. And yet the Galápagos remain the best living evidence of the sort of flowering of life that occurs on volcanic islands.

These contrasting stories raise the question of why we have been left so few islands where a great deal of diversity has been preserved, as it has on the Galápagos, and so many islands where diversity has largely been lost, as on Easter Island. However, Easter Island is perhaps not the best place to find the answer to that question. Much of what has been surmised about its decline is disputed. The theory that Easter Islanders brought about the doom of their civilization by shortsightedly cutting down all the trees is undermined, some believe, by recent evidence suggesting that rats brought there by the first settlers (rather than the settlers themselves) caused the deforestation, by eating seeds that would otherwise have become trees.

More is known about what happened on the Mascarene Islands—Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues, which lie a thousand kilometers east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Here much of the ecological drama was recorded as it unfolded. And now life on the Mascarenes has been described in great detail by Anthony Cheke and Julian Hume in Lost Land of the Dodo. They tell the story of the islands in three acts—the evolution of the biota, the impact of humans from the 17th century onward, and the future prospects for restoration of the islands’ devastated ecosystem.

Like the Galápagos and Easter Island, Mauritius, Réunion and Rodrigues are volcanic in origin. Seen from above, Réunion looks like a green rock—a moss-covered stone. Farther east is Mauritius, similar in size, and beyond it lies Rodrigues. Expanses of ocean hundreds of kilometers wide separate the three from any other land.

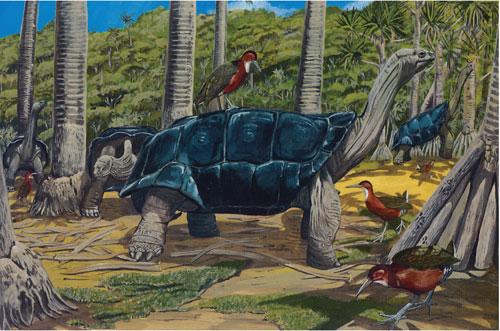

From Lost Land of the Dodo.

Cheke and Hume describe in great detail the origin, composition, biota, ecology and history of each island. But the most compelling depictions are visual—a series of 39 colorful paintings by Hume. These illustrations show a landscape so inviting that I was inspired to check on the cost of a flight to Mauritius. In one painting giant raven parrots (Lophopsittacus mauritianus) walk among tree roots. Another shows a hillside on the coast of Rodrigues carpeted with giant tortoises, re-creating a scene described by Francois Leguat, who lived on Rodrigues for two years beginning in 1690 and claimed he was able to walk for a hundred paces across the backs of the tortoises. Still others depict Mascarene parrots (Mascarinus mascarinus), a Réunion echo parakeet (Psittacula eques), Dubois’s parrot (described only once, in 1674), Réunion ibises (Threskiornis solitarius), hoopoe starlings (Fregilupus varius), flying foxes (Pteropus niger), a flightless wood-rail (Dryolimnas augusti) riding on a tortoise, and even a dodo (Raphus cucullatus) bending its head to preen.

These paintings alone are worth the price of the book. They are surely among the best re-creations of an island world. But they are just that, re-creations. Almost all of the species in the paintings are extinct. So the images are also simply sad.

After describing the flora and fauna that once flourished on the islands, the authors get down to the business of explaining what became of them. The records Cheke and Hume find are rich and, often, specific. The fall of the most fragile native species was observed and noted. Many losses can even be attributed to a particular cause. The authors reconstruct for the reader—species by species—just what happened. For almost no other islands has it been possible to explain the extinctions in such detail.

From Lost Land of the Dodo.

Consider what the world’s islands would be like if history had gone differently. The Galápagos have experienced some environmental degradation, but people began conservation efforts there relatively early, and as a consequence many endemic species remain. Had we done the same on other islands, we could have spent generations documenting the life on them. Each island has different species, and so does each archipelago. The differences increase over time, each island drifting in its own direction. To have known well the fauna of islands would have given us the best possible window into the history and possibilities of life.

But our behavior has rarely been benign. Humans arrived in North America and the Pleistocene megafauna went extinct. We arrived in Australia and the same thing happened. We made it to oceanic islands and the waves of extinctions continued. Instead of growing more different with time, the isolated regions of the world have become more similar as a result of extinctions and introduced species.

In the Mascarenes, as elsewhere, the first humans to arrive were at best ignorant, at worst aggressive in their antagonism toward nature. It was realized early that something needed to be done to conserve forests. On Mauritius, the French government began to regulate hunting and forest clearance as early as the late 1700s. Initially conservation projects ignored rare species, but by the early 1800s (when the reality of extinctions was all too apparent), that changed. In theory all that was missing was the realization that nonnative species (including pigs, monkeys, deer and rats) needed to be extirpated rather than encouraged. But the efforts to get rid of them were too little, and even by the 1700s already too late. Some species were saved by the early conservation efforts or survived on smaller islands that were more remote, but just as many were lost.

As for what caused the native species and habitats of the islands to decline, it was rats. But it was also forest clearance and hunting, pigs and monkeys, agriculture and erosion. Just about everything you can imagine played a role. What the Mascarenes have to teach us is that when we recognize that the environment is being degraded, we must act quickly and effectively. Otherwise, the deterioration will continue: Species will disappear, and the forest will dwindle. Our descendants will look back at our well-documented catastrophe and wonder why we dithered.

Lost Land of the Dodo is not a fast read. It is thick with details. Nearly 200 pages are taken up by the endnotes and references. But it is the details that make it a necessary read. Here is the story of what can happen to an island when we ignore the consequences of our actions.

Rob Dunn is an assistant professor in the department of biology at North Carolina State University. He is the author of Every Living Thing: Man’s Obsessive Quest to Catalog Life, from Nanobacteria to New Monkeys (HarperCollins, 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.