A Pandemic of Confusion

By Jeffrey H. Toney, Stephanie Ishack

Conflicting messages have characterized not just COVID-19, but also many past disease outbreaks.

Conflicting messages have characterized not just COVID-19, but also many past disease outbreaks.

In the United Kingdom, a rapidly spreading novel disease incapacitated the prime minister for several weeks. Parliament suspended committee work, postal services and railways shut down, and the number of infections rose as most citizens ignored advice to stay home. This chaos and loss of lives began in November but wasn’t reported until mid-December. Whether the illness could be transmitted from person to person was debated. This question was resolved by late January. In London, more than 1,000 deaths due to pneumonia were reported over a one-week period.

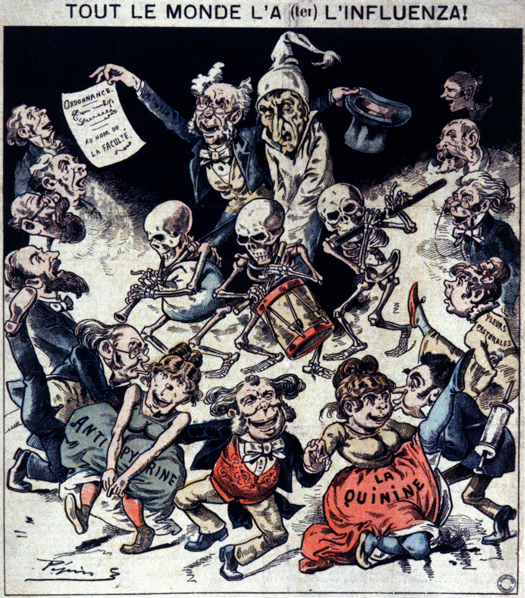

This scenario, which could well have taken place during today’s COVID-19 pandemic, occurred 130 years ago. The Russian flu of 1890 killed some 1 million people and may have been caused by a coronavirus, as has been suggested by researchers at the University of Leuven in Belgium. Previous pandemics show that conflicting messages and questioning public health information are common responses to crises of this scale. History repeats and infections repeat, because confusion and misinformation are endemic in human nature. This fact and these histories point to ways to improve public health communication today.

IanDagnall Computing/Alamy Stock Photo

Queen Victoria’s grandson and heir, Prince Albert Victor, succumbed to the 1890 outbreak, dying of pneumonia at the age of 28. No one knew at the time that this pandemic was caused by a virus. The first virus linked to human disease, the yellow fever virus, was not discovered until 1901.

The pandemic of 1918—caused by an ancestor of the influenza virus H1N1—was even more devastating than the Russian flu, taking between 50 million and 100 million lives, at the same time that more than 20 million lives were lost in World War I. Although the pandemic was commonly referred to as the Spanish flu, its origins are murky. At the time, U.S. Army Medical Corps physician James J. King told the Chattanooga News that the virus was from Chinese workers sent to France, some of whom were captured by Germans and infected their troops, who then took the plague to Spain and around the world. But the virus may well have originated in the United States, according to a 2019 article in Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health.

Police and public health officials tried to enforce measures such as use of face masks, but they encountered public resistance. The Anti-Mask League formed in San Francisco, led by civil rights activist Emma Harrington. This group complained about the use of an “insanitary and useless mask,” according to the Stockton Daily Evening Standard on January 21, 1918. Keeping gauze masks sanitary at that time was a challenge, because washing after use had to be done by hand. In October 1918, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that a blacksmith urged a crowd to dispense with their masks, shouting “They are the bunk!” When a health department inspector led him to a drugstore to purchase a mask, the blacksmith pummeled him with a sack of silver dollars. The health inspector drew his revolver, shooting the blacksmith and two nearby shoppers (all of whom survived).

CCI ARCHIVES/Science Source

A few days before Thanksgiving 1918, the mayor of Denver at first said that a mandate to wear “flu” masks in church, on streetcars, and in stores and theaters “could not be enforced,” according to The Denver Post. Nonetheless, police officers enforced the order by preventing those without face masks from riding on streetcars. Ushers at theaters ejected anyone not wearing a face mask, but churchgoers could attend services without one. About a week later, 22 physicians from Salt Lake City, including Clarence O. Eddy, assistant surgeon general of the United States, wrote in the Salt Lake Tribune that wearing masks “as a universal compulsory measure is not only impractical and ineffective, but may become a positive menace.” Meanwhile, Indiana physician Herman G. Morgan pointed out that fewer cases of influenza had been reported while almost everyone was complying, telling the Indianapolis News on November 19, 1918, that the “epidemic fight is up to the people.” Physician Henry Bracken of Minnesota’s State Board of Health supported wearing masks, but did not use one himself, telling the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “I personally prefer to take my chances.”

These examples of skepticism about the importance of wearing face masks, and the blacksmith’s fierce defense of individual liberty that endangered him and those around him, help contextualize the deeply divided reactions seen today. Political philosopher Michael Sandel of Harvard University ascribes American resistance to public health mandates during the COVID-19 pandemic as a “new front in the culture wars.” Resentment of government policies based on science and the emergence of “anti-science” views today are reminiscent of debates about faith versus reason dating back to Aristotle and Plato.

All the examples above could have been reported in 2020, except for the use of a sack of silver dollars as a weapon. The lesson we should take from past pandemics is not that history will inevitably repeat itself, but that it is important to tell the truth. Without truth, there cannot be trust in government mandates intended to protect public health.

The horrid SARS-CoV-2 virus, whose tiny RNA genome consists of about 30,000 base pairs, which is about 0.001 percent the size of the human genome, has a single goal: to make copies of itself. The virus may have found the perfect host at the most opportune time. Humans are a Hot Springs luxury resort for SARS-CoV-2. We are a highly social, interconnected, interdependent, tactile, affectionate species. We prefer living in high population densities, migrate globally in large groups within hours, and currently lack antibodies to stop the infection. Our social groups are diverse and are often confused by mixed public health messages, in a divisive political environment that for generations has been more reactive than proactive when faced with crises. We humans are easily distracted, have short attention spans, and tend to find ourselves learning the same lessons over and over again. In his 2012 book America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, environmental historian Alfred Crosby points out that, despite the devastation, Americans “took little notice . . . then quickly forgot what little they did notice.”

These ideal conditions for transmission have resulted in efficient, rapid global spread of COVID-19. Worldwide, the number of SARS-CoV-2 infections continues to increase. The disease was first reported in Wuhan, China, on December 31, 2019, and by September 22, 2020, more than 31 million cases had been confirmed and the death toll had exceeded 968,000.

Although the biology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus cannot be changed (at least not quickly), our behavior can change to slow or even stop its spread. An August 6 report by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimated that universal mask wearing could prevent 66,000 of the 140,000 deaths projected to occur between August 6 and December 1, 2020. A retrospective analysis published April 9 in the British Medical Journal by Trisha Greenhalgh of the University of Oxford and her colleagues further supports wearing masks as an important public health measure.

Confusing, inconsistent public health messages about pandemics are nothing new. Whether it’s the Russian flu of 1890, the Spanish flu of 1918, COVID-19 of 2019, or the next pandemic wave, it is unlikely that such contradictory messages will be cleared up.

Since the beginning of the current pandemic, the news media and social media have highlighted a range of confusing, often contradictory messages about COVID-19, such as these:

COVID-19 does not transmit from person to person.

COVID-19 is highly contagious.

Messages can change as our scientific understanding of COVID-19 evolves. The World Health Organization (WHO) informed the public on January 14 that there is “no clear evidence of human-to-human transmission.” Although the statement was technically accurate, lack of evidence does not mean that human-to-human transmission cannot occur. Indeed, the first case of COVID-19 in the United States was reported only six days later. On February 16 WHO reported “high levels of community transmission,” based on clear, mounting evidence in several countries.

Political agendas and racism underlie certain conflicting messages, such as these:

African Americans are immune.

African Americans are highly vulnerable.

Epidemiologist Clarence Spigner of the University of Washington points out that myths about immunity among African Americans date as far back as the yellow fever epidemic in 1792. This myth resurfaced on social media in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, because initial cases in the United States were largely among middle- and upper-class white people who recently had traveled. But media continued to focus on infected white people after the disease spread through the multiracial U.S. population, or to focus on Asians with the disease. The immunity myths were easily debunked as hospitalizations and deaths in the African American community increased, clearly demonstrating that they, as well as Hispanic and Indigenous peoples, are disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Conflicting messages also resulted from balancing protection of health care workers and the general public when faced with limited supplies. An example:

Don’t buy masks!!

You must wear a mask.

On February 29, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams tweeted, “STOP BUYING MASKS!” This message unfortunately led to confusion despite his good intentions: He had been responding to reports of health care workers who were put at risk as medical grade masks were rationed. On May 25, Adams told the public that the “best current science, never politics,” informed his advice, as he asked citizens to choose to wear a mask in public to protect the vulnerable.

Although these messages were based on the latest available reports from medical centers, their deliveries were confusing. The public is witnessing in real time the scientific community grapple with a novel virus, as they search for the best methods for diagnostic testing, treatment, and vaccine development, while the pandemic rages on and death tolls mount. In response to urgent public demand for the latest information, releasing results before deliberative peer review can be warranted but bears risk of misunderstanding conclusions or even of retraction as more thorough studies are conducted. Balancing expediency with accuracy and reliability during a pandemic ultimately depends on reliance on and trust in the professional judgement of scientists and physicians.

From Twitter

One approach to effective public communication during a health crisis, particularly when fear and uncertainty are heightened, is to connect with audiences through emotion and values, using nonjudgmental narratives that highlight empathy and understanding. Art, music, film, and video all can connect on an emotional level. Amy Lesen, an environmental studies professor at Tulane University, believes that art can engage the audience through attitude and emotion, thereby “catalyzing creativity and discovery by encouraging intuitive thinking,” as she and coauthors wrote in Trends in Ecology and Evolution in 2016. Their research suggests that art-based communication is most effective when it is interactive. Moreover, they suggest that community-based approaches in which the audience members become “makers of art” or collaborators are especially impactful. One successful example is the art-based climate project called HighWaterLine, in which artist Eve Mosher uses workshops and public art activities to encourage communities to prepare for and cope with the effects of climate change. (For more on this project, see Arts Lab, March–April 2015.)

George Miller’s 1992 film Lorenzo’s Oil is a compelling example of communicating complex medical concepts to the public through emotion and storytelling. This film is based on the true story of how Lorenzo’s parents, who were not scientists, learned about complex biochemical pathways in an effort to save their young son from the devastating effects of a rare genetic disorder, adrenoleukodystrophy. Videos can be effective in reaching wide audiences using social media, particularly if they include entertaining content. The video Global COVID-19 Prevention by Stanford Medicine’s Maya Adam uses animation and humor to educate the public about best practices to curb the pandemic. It currently has more than 1 million views.

Maya Adam/Stanford Medicine

However, most media related to COVID-19 do not employ narratives, metaphors, descriptive words, or images. Indeed, some of the most popular videos simply capture behavior that puts public health at risk, such as people refusing to wear a mask or congregating in large groups. We recommend instead using more imaginative elements that will engage people on a deeper, more cognitive level through the use of video, music, and humor. Delivering a relatable story line and featuring people who share viewers’ identities develops an emotional connection to the material.

Community-centered responses may also include offering webinars on the importance of mask wearing and social distancing, and providing more educational content such as videos or podcasts on the evolution of scientific information about COVID-19.

The pandemic that has rocked the core of our society, ripping us apart, can become an opportunity to bring us closer together and slow down or completely avoid the next wave of this pandemic. As technology advances toward safe, effective vaccines and antiviral therapies, human nature will remain the same. In the end, empathy and the resolve to protect one another could be the most important factors in saving as many lives as possible.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.