The Inimitable Caroline

By J D Fernie

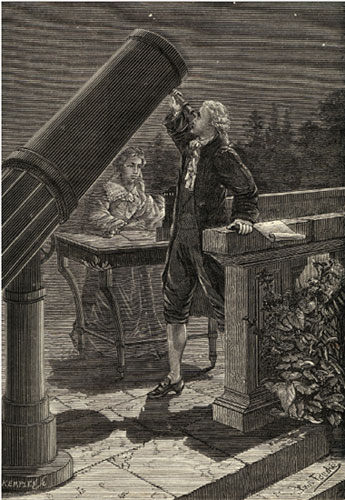

The sister of British astronomer William Herschel was herself a capable and pioneering celestial observer

The sister of British astronomer William Herschel was herself a capable and pioneering celestial observer

DOI: 10.1511/2007.68.486

It is often said that behind every successful man there is a woman. She is usually a wife or mother; less often is she a sister. But such was the case for the pioneering 18th-century astronomer William Herschel. His eventual success as a scientist was due in no small measure to his sister, Caroline.

Born in 1738 to a musical family in Hanover, in what would later become Germany, William became an oboist in a military band while still a teenager. He abandoned this career upon discovering that the musicians, having marched the soldiers into battle, had to fend for themselves during actual combat. Cowering in wet ditches while musket and cannon balls whistled overhead did not augur well for either health or longevity, so William decided to pursue his musical career elsewhere. At 19 he made his way to England and in 1766 became organist and orchestra leader at the fashionable resort of Bath. Here he gave thought to his sister.

Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy

Caroline was 12 years younger than William, and like him, she inherited their father's musical talent. With few career options open to women of her time, her desperate wish was to achieve sufficient education to become a governess teaching music and literature. Her father was sympathetic to the idea, but her mother dismissed it. As a result, her father's death in 1767 condemned Caroline to be little more than a teenage drudge in the family kitchen. When William invited her to join his musical world in Bath she leapt at the opportunity.

Life in Bath fulfilled Caroline's wishes, at least in the beginning. The siblings were immersed in musical activities, and Caroline took several singing lessons a day from her brother, now the choirmaster of the well-to-do Octagon Chapel. (It is often assumed because of their name that the Herschels were Jewish, but family records show they were not. Indeed, John Herschel, William's son, who became the most famous scientist of mid-19th-century England, is buried in the Anglican Church's Westminster Abbey.)

William lived a busy life as the chapel choirmaster, organizing and producing public concerts and composing music in his free time. His sister's way was less clear. English proved to be a difficult language for Caroline, and she made few friends. Her hope for an independent musical career faltered. William evidently concluded that her musical talent was limited, and he did not encourage her to continue.

Soon a new routine entered their lives. Each evening, as William returned home and immediately retired to bed, exhausted by the day's musical activities, he took with him "a bason of milk" and a book on astronomy. Over breakfast the following day, he would present "an astronomical lecture." After reading the few available books on astronomy, he decided to build telescopes and scan the heavens. Before long, Caroline found herself wrapped up in her brother's new obsession, writing that she was "much hindered in my [musical] practice by my help being continually wanted in the execution of the various astronomical contrivances." Indeed, William was on the cusp of a second career.

It is fortunate that Herschel had no formal training as an astronomer before starting his observations. If he had, the experts of the day would have taught him the futility of looking at stars, which were mere points of light. According to those learned masters, the only interesting things were solar-system objects! But unencumbered by expert opinion, William decided to study stars. To do this, especially if he wanted to see the lesser known, fainter ones, he needed a large telescope. So he decided to build one.

It was precisely at this point that the genius of William Herschel was established. His eventual fame among astronomers came not from any great insights into astronomy itself—indeed it might be said that his fame was established despite some of his beliefs. For example, he long held that the Moon was almost certainly inhabited as very likely was the Sun. In the latter case, Herschel opined, the inhabitants lived well below its fiery cover, protected by very dense clouds through which tall mountains occasionally protruded, which appeared as dark sunspots to us. The establishment of the time, although it knew almost nothing of astronomical physics, had no doubt that Herschel must be wrong on such matters. (In his defense, other conclusions of William's, such as his claim that the Sun could not be at the center of the Milky Way, were correct; yet they met with the same disbelief.) What his contemporaries soon came to realize, however, was that Herschel built better telescopes than any the world had ever seen.

And so life for the Herschel siblings became more hectic. It was still music that formed the basis of their livelihood: endless rounds of concerts and student lessons, responsibility for all Sunday morning musical matters at Octagon Chapel, and composition. (William wrote some of the most charming music of the time, and a number of his symphonies remain popular to this day, selling well in CD recordings.) But in the midst of all this, the building of telescopes grew steadily more important. At critical stages during production of a new telescope, all else was put aside. Caroline writes of her "attendance on my Brother when polishing [a new mirror], that by way of keeping him alife I was obliged to feed him by putting Vitals by bitts into his mouth—this was once the case when at the finishing of a 7 feet mirror he had not left his hands from it for 16 hours together."

William's reputation as a telescope maker began to be noticed, even by such notables as the Astronomer Royal, and it eventually led to an invitation to take one of his telescopes to the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. There it was set alongside the best of the Observatory telescopes for comparison. William later reported that "These two last nights I have been star-gazing at Greenwich with Dr Maskelyne [the Astronomer Royal]. . . . We have compared our telescopes together, and mine was found very superior to any of the Royal Observatory. Double stars which they could not see with their instruments I had the pleasure to show them very plainly. . . ."

The superiority of William Herschel's instrumentation became incontestable in March 1781. On the 13th of that month William happened to have his telescope turned to the region of sky near the star Zeta Tauri. He immediately noticed that one star in the field of view appeared different than the others. Although all stars viewed telescopically show some kind of surrounding disk (for purely optical reasons), this one had a significantly larger disk than its neighbors. William concluded, reasonably enough, that it was likely a comet, tail-less because of its distance from the sun. He carefully noted its position in the sky relative to the surrounding stars, and on returning to it a few nights later found to his satisfaction that it had indeed changed position. It must surely be a comet! He sent a report to the Astronomer Royal, hoping for quick verification, only to hear that the telescopes at the Royal Observatory were so inferior that all the stars in the area showed significant disks. The Greenwich observers would have to measure and re-measure the positions of all objects in the area to find which one was moving. When that was done, however, the result was startling. Unlike the elongated, tilted orbit of a typical comet, this object had an orbit typical of a major planet! In fact, there was no alternative. This was a major planet—the first ever discovered in modern times.

Herschel was still completely unknown in astronomical circles, so that early announcements of his discovery carried many misspellings of his name, and there was general misapprehension as to who he was. Still, as the finder it was his right to name the new planet. He decided to name it Georgium Sidus ("George's Star") after the king of England, young George III. (Never popular with foreign astronomers, the name was changed to Uranus, a Latinized version of the Greek god Ouranos, in the years after Herschel's death.). The King already had a former tutor who served as the King's Astronomer (as distinct from the Astronomer Royal, the latter being defined as the head of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich), but that person was elderly and in the background. In fairly short order, thanks mostly to friends in high places, William was invited to become the King's Astronomer.

It was a mixed blessing. The new position meant a reduction in income and required the Herschels to live near the palace and be available on any clear night the King felt like being entertained astronomically. However, it allowed William to pursue astronomy without distraction. And so the professional musical careers of both William and Caroline came to an end. They moved house to be close to the King at Windsor Castle, and William soon developed a thriving telescope-making business that enabled him to continue his nighttime observations. Caroline managed the flow of data, reducing each night's observations to a usable form, making legible copies and often carrying it to London for publication. This being the 18th century, she was also responsible for keeping house and providing meals.

One pictures the brother and sister in their small house eating dinner, only to have a knock on the door reveal some lackey announcing that the King and his entourage would be arriving shortly at the Herschel house to be entertained by the view through the new 40-foot telescope. (Forty feet referred to the instrument's focal length, not its aperture, as it would in today's terminology.) This remarkable instrument had been paid for by the King, who felt no hesitation demanding its use. On one such occasion, the royal party included the elderly Archbishop of Canterbury, who viewed the huge telescope with its ladders and struts with some consternation. As the story goes, the enthusiastic King held out a helping hand to the Archbishop and cried, "Come, my Lord Bishop, I will show you the way to Heaven."

Caroline soon began to pursue her own observations. William built a telescope for her that was smaller than the massive 40-footer, but powerful enough for her to discover a number of comets. More importantly, she joined him in sweeping the skies for nebulae. Through their individual efforts, the number of known nebulae grew from about 100 to more than 2,500 by the time they finished.

At other times Caroline assisted with the big telescope. On a bitterly cold night at the end of 1783,

"My brother . . . directed me to make some alteration in the lateral motion, which was done by machinery. . . . At each end of the machine . . . was an iron hook such as butchers use for hanging their joints upon, and having to run in the dark on ground covered a foot deep with melting snow, I fell on one of these hooks which entered my right leg about 6 inches above my knee; my brother's call "Make haste!" I could only answer by a pitiful cry "I am hooked." He and the workman were instantly with me, but they could not lift me without leaving nearly 2 oz. of my flesh behind. The workman's wife was called but was afraid to do anything, and I was obliged to be my own surgeon."

In 1788 when she was 38, Caroline's life fell apart. William, nearly 50, married a rich widow, upsetting the collegial relationship between the two siblings. The bride, it seems, made considerable effort to soothe and placate her new sister-in-law, but to no avail. Caroline soon moved to new lodgings and began a new journal to express her feelings. Many years later, when she finally made peace with herself, she destroyed every page of that journal and adopted a much more benign view of her sister-in-law. But even prior to this reconciliation, Caroline took great delight in her young nephew, William's son John. Nevertheless, when William died in 1822, she immediately left England and returned to Hanover, a decision she later regretted. Her good spirits returned, however, and she lived to the remarkable age of 98, her mind lively to the end.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.