The History of Vaccine Uptake in Taiwan

By HungYin Tsai

When the bubonic plague pandemic hit in 1896, soon after Japan had colonized the island, social and political forces led residents to resist public health initiatives.

When the bubonic plague pandemic hit in 1896, soon after Japan had colonized the island, social and political forces led residents to resist public health initiatives.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw a resurgence in phenomena that we thought were things of the past.

Not only did we see hospitals fill up and many tragic deaths, but we also saw resistance to vaccines, masks, and quarantine and isolation. (See “A Pandemic of Confusion,” November–December 2020.) If history repeats, it may also hold lessons: How did people overcome medical resistance in pandemics of yore?

The plague outbreak in 1896 and cholera outbreak in 1919 in Taiwan offer some perspective. Vaccine hesitancy and resistance to public health measures first emerged there during the 1896 outbreak. But Taiwan was able to overcome later pandemics. A few decades after the first plague outbreak, people on the island devoted themselves to public health, and the plague was largely controlled. They also lined up to be vaccinated against cholera, even though they had strongly resisted vaccination before. To understand why requires stepping back in time, to Japanese colonization in 1895, just before the plague outbreak hit the island.

During the Japanese colonization of Taiwan from 1895 to 1945, the island experienced an unprecedented outbreak of bubonic plague that began in 1896, as well as the lingering threat of cholera. This island, which is slightly bigger than the country of Belgium and sits in a vital trade position in the eastern Pacific Ocean, bridges northeast and southeast Asia. At the time, nearly 3 million people lived on the island. Historically known as Formosa, the island was the home of pirates before the colonizers came, and it was the forward base for imperialists to move wherever they wanted. This geographical location was a blessing for Taiwan’s economic and cultural development but made it vulnerable to imported diseases.

The plague outbreak in 1896 might have been part of a global pandemic known as the “third plague pandemic,” which lasted from 1855 to 1960. This 105-year pandemic started in Asia and reached most of the world’s populations within a few years.

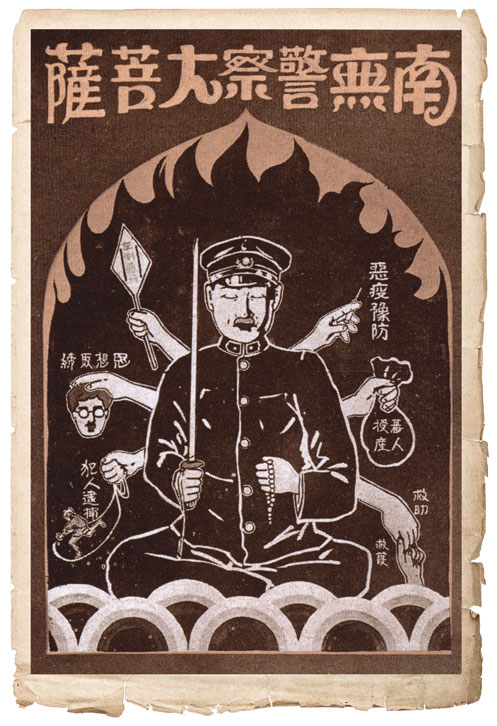

The Collections from the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

The history of Taiwan demonstrates how people decide whether to trust vaccines and other public health measures. Throughout Japanese colonization, approaches to pandemics varied substantially, resulting in very different vaccine uptake rates and, more importantly, affecting the long-term solidarity between society, medicine, and the government.

The response to a disease is always a combination of general aspects of human nature and a specific cultural and social setting. The plague hit at a particularly turbulent time in Taiwan’s history. The Spanish and the Dutch East India Company established trading bases in Taiwan in the 17th century for a short period of time. Japan defeated the Qing Empire (China) in 1895, becoming the first modern Asian colonial empire, with Taiwan secured as its first colonial possession. Indigenous peoples have lived on the island since about 5000 BCE. Starting in the 16th century, Chinese immigrants began moving to Taiwan. Thus, it was home to many kinds of traditional medicine, including Indigenous medicine and Chinese medicine, the latter brought to Taiwan by southeastern Chinese immigrants.

After Taiwan became a Japanese colony in 1895, those traditions were forcibly swept away as the colonists charged ahead with a westernization agenda, recognizing only modern medicine; Japan also abandoned its own traditional medicine, Kampo. The Japanese colonial government forbid practicing medicine without a license and did not offer licenses for those practicing traditional medicine on the island, effectively banning its practice. Failing to recognize local healers paved the way for Taiwanese mistrust of Japanese-imported medicine.

When the plague struck Taiwan in 1896, Japan quickly launched a series of science-based actions to control the outbreak. At that time, the germ theory of disease—the idea that pathogens cause infectious diseases—had been recently popularized by the likes of the great microbiologists John Snow, Louis Pasteur, Robert Koch, and Kitasato Shibasaburō. Drawing on this theory, Japan began requiring quarantines, inspecting ships and travelers, segregating all patients from their families, isolating patients in specialized “plague” hospitals, and requiring the families of those patients to stay inside their homes for about seven days. If the patient passed away, the body had to be cremated to eliminate any possibility of transmission. This requirement violated local burial practices believed to comfort the spirits of the deceased and their living families.

The Collections from the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

These actions made sense from a scientific perspective, but enforcing them was not always practical. At the time of the outbreak, the Japanese authority had only recently landed on the island. Along their way from the north to the south of Taiwan, the colonizers were met with resistance. These conflicts caused around 300 deaths of Japanese soldiers and more than 10,000 deaths of Taiwanese locals in 1895. But in some places, such as the cities of Taipei and Tainan, local community leaders worked with Japan and opened their doors to the empire’s military. The colonial authority and local leaders were unfamiliar with one another, but they tried to work together to bring peace to these cities. By 1896, when the plague outbreak hit, Taiwanese society was coming to peace with, but still hesitant toward, Japanese authority.

Japanese physicians at the time claimed that the plague had come to the island because of trade activity between Taiwan and Xiamen, a treaty port in south China that had suffered a plague outbreak in 1894. Most Taiwanese, on the other hand, believed that the plague had come from the Japanese colonizers, because there had been no outbreak in Taiwan before they came to power. Thus the colonizers and the colonized blamed one another for the spread of the disease, entrenching resentments and foiling attempts to cooperate.

Nowhere were the Taiwanese people’s fears and violations of pandemic rules more evident than in relation to hospitals. All the physicians at these hospitals spoke Japanese, a language that very few Taiwanese understood, alienating the public from the official plague-control response. The hospitals also isolated plague patients from their families and communities to control the spread of the disease, a practice that scared and angered many local people.

The gap between the promises made about modern medicine and the limited effectiveness of the available treatments bothered local people as well. Antibiotics would not be available until the mid-20th century, so physicians could only provide medical interventions that we now know were terrible—for example, extracting patients’ lymph nodes or injecting patients with disinfectant. These treatments tended to fail, and most hospital patients died.

Surviving records of the prevalence and mortality rate of this plague are inaccurate, because many people avoided government institutions and were never counted. But medical records in the two plague hospitals in Taipei show that in 1896 the mortality rate after receiving curative treatments was 53 percent, not much lower than the 60 percent mortality rate of plague victims recorded by the government that year (the latter attempted to include those who died outside of hospitals). Although Japanese physicians were proud of their modern medicine, the low survival rate was a sign to the local population to avoid hospitals. A petition from May 16, 1898, urged the colonial government to leave the Taiwanese people alone. The petition stated [translated from written Chinese], “If one was taken into the hospital by the police and treated by Japanese [modern] medicine, less than 1 in 10 would survive. But if one were sent to the rural area and treated with local medicine, 8 or 9 of 10 would survive.” More than 140 businesses in Taipei signed this petition, reflecting the local community’s general view of hospitals. In short, they viewed these isolation hospitals as a combination of prisons and death camps.

Later in the 1920s, Tu Tsung-Ming, who held the distinction of being the first Taiwanese MD PhD trained in Japan, commented on the limits of clinical treatments, even though he fully embraced modern medicine [translated from Japanese]: “I must confess that [traditional] . . . medical treatments can cure every cholera and plague patient, but a dignified, skilled practitioner of Western medicine can do nothing in this area—almost all of his patients will die.” Although all the statistics about mortality during these outbreaks are limited in accuracy, the evidence indicates overall that survival was higher among people who left the cities and received traditional medicine than it was among people in the cities receiving modern medicine.

Because of the high mortality rates and brutal therapies in plague hospitals, rumors spread that Japanese physicians were killing local people in hospital isolation wards. This misinformation was the result of political and medical distrust, rather than its cause, because it did not appear until conflicts over the hospitals and quarantines occurred. Distrust inspired misinformation, and then misinformation deepened the distrust of the government and modern medicine, in a self-reinforcing cycle. Outlandish rumors spread quickly, some even claiming that the Japanese would eat humans in the plague hospitals—a crime hidden by the cremations.

The Collections from the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

Local Taiwanese people in the cities, where there were more Japanese physicians and police surveillance, lived in fear of hospitals, physicians, and police. On the other hand, the Japanese authorities were also upset, because they worked hard to implement an advanced public health strategy to fight the outbreak, only to have it thwarted by locals whom they saw as uneducated. Thus, the outbreak raged on and threatened business activities and populations on the island, which were already vulnerable amidst the political instability of a new colony.

Growing fears of the official medical response to the plague led many Taiwanese people to hide from authorities. If a Taiwanese family suspected that a relative was infected, they would hide that person at home or send them to the countryside under the cover of night. If a hidden person died, their family would either bury the body at night, when authorities were least likely to be around, or they would simply throw the body away. The families of patients didn’t want to be quarantined, either. If they were forced to stay home, they could not earn a living. Local newspapers reported rampant violations of public health rules.

Initially, the Japanese colonial government responded to these violations with strong-armed police action. The police patrolled the streets and dragged anyone who looked sick to the hospital. A local entrepreneur, Lí Chhun-Seng, who was among the first few Christian Taiwanese people exposed to Western culture and one of the most influential community leaders, commented in the Taiwan New Newspaper in 1896 that the Taiwanese had their folk practices to handle pandemics, and he told the colonizers to leave Taiwanese people alone. Yet for the time being, the colonial government did not heed his advice.

These divisions had tragic consequences for both Japanese and Taiwanese residents. The plague continued to threaten them for many years. According to the published official statistics, 566 people died of plague in 1897, and the annual number of deaths grew to 3,670 in 1901, even though a plague vaccine came out that year.

The profound distrust between the Japanese-dominated health officials and the local Taiwanese population later shaped the attitudes toward vaccines. The tension erupted in a 1902 community meeting between local leaders, traditional healers, and the Japanese health authority in Taipei. As reported in the Taiwan New Newspaper on March 25, 1902, Japanese government physicians called a meeting with local community leaders and licensed local practitioners of traditional medicine. In this meeting, a Japanese physician, Horiuchi Tsugio, announced that a vaccine was available to prevent the plague, and that all licensed local healers should receive the jab, because they were “educated” members of the community, as a way of encouraging all Taiwanese people to do the same. From the perspective of Japanese physicians, this vaccine was the most advanced medical technology at that time, and it could stop the plague’s spread and death toll. However, because of the coercive tactics that had been employed by Japanese authorities during the pandemic, locals remained hesitant about all modern medicine and government health policies.

The Collections from the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

Several days later, this Plague-Vaccination Meeting received further coverage in the Taiwan New Newspaper. According to the report, a practitioner of traditional medicine attending the meeting described to Horiuchi how almost all Taiwanese people in Taipei were strongly opposed to the shots. Taipei residents were concerned, because during an early vaccination campaign, the only Taiwanese person to voluntarily receive the vaccination (locals described him as “crazy” for doing so) had died of plague soon after. This case had shocked locals because Japanese physicians had claimed that the vaccine was modern, safe, and effective. Of course, there were reasonable explanations as to why a safe and effective vaccine could not save this one person. Nevertheless, more misinformation and conspiracies circulated after the man’s death, claiming that the vaccine was poisonous or designed to kill the Taiwanese people.

This man’s name, the exact date of this occurrence, and details about his vaccination were not recorded in official documents, such as newspapers and government archives. This dearth of information reflects another common issue with imperial medicine: a lack of transparency. Because the colonial government wanted to maintain its medical legitimacy and worried about further vaccine hesitancy, official documents often concealed controversies. But according to the Taiwan New Newspaper’s report, the story of this adverse event spread quickly among practitioners of traditional medicine and local residents.

When local practitioners of traditional medicine asked Horiuchi about this concerning case at the meeting, he speculated that the man may have already been infected with plague when he was vaccinated. When the local healers continued to argue with Horiuchi, he blamed the traditional medicine the patient received as treatment for the plague, and he denied any adverse effects of the vaccine. Unsurprisingly, the Japanese colonists lost the support of community leaders and local practitioners of traditional medicine, and the plague vaccination campaign failed.

Only Japanese communities on the island were willing to receive shots, and the Taiwanese people, who comprised the majority of the population, remained hesitant about this vaccine. In 1903, 12 percent of the Japanese population in Taipei received the plague vaccine, while only 5 percent of the Taiwanese did so. The plague continued threatening the island until 1917, causing around 24,000 deaths, the majority of whom were Taiwanese, with an approximate overall mortality rate of 80 percent.

The Plague-Vaccination Meeting in Taipei, which took place almost 120 years ago, foreshadowed the contemporary antivaccination movements and mistrust toward modern medicine and government authority that we see today. When pandemics hit Taiwan over a century ago, a politically and socially polarized society became more polarized. The fight against misinformation became endless, because it did not address the root of the problem: the ingrained distrust between the ruling class and state-sanctioned physicians on the one side, and local Taiwanese on the other.

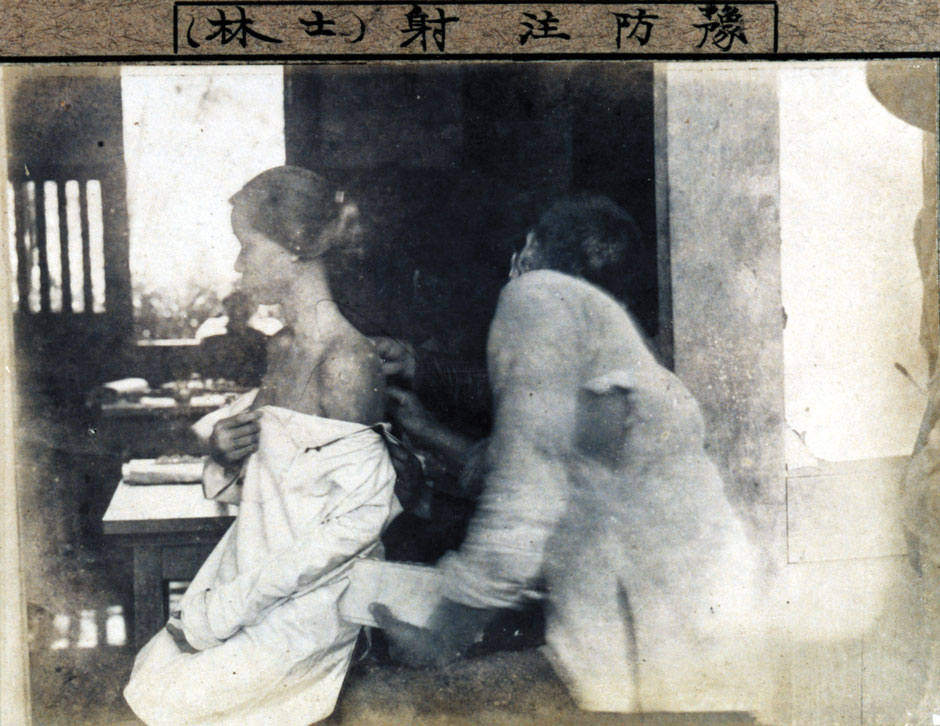

History, it turns out, does not necessarily repeat. The Japanese and Taiwanese learned from the plague pandemic, and they successfully maintained public health during later disease outbreaks. In 1919–1920, many years after the first 1896 outbreak of plague, the Taiwanese people lined up outside of vaccine stations waiting for their shots against cholera, a disease that had threatened local communities for years, well before colonization. Plague and cholera were controlled in Taiwan in 1918 and 1920, respectively, a tremendous public health success at the time. What changed?

One dramatic difference was the emergence of new social elites. The colonial government continued to encourage Taiwanese to use modern medicine, and a community of Taiwanese elites received modern medical training at the Taiwan Colonial Government Medical School, established in 1899. These elites became fixtures in the local political, economic, and cultural scenes, and they had credibility as authentic Taiwanese voices. Some of these elite physicians would eventually lead the local resistance to Japanese rule.

These Taiwanese physicians not only became new social elites, but they also claimed modern medicine for the colonized. For local people, practitioners of modern medicine were no longer “others”; rather, these new Taiwanese physicians were members of the community who stood up for their rights against the colonial authority. Some Taiwanese physicians became government officials who offered public health services, such as monitoring disease outbreaks, prescribing drugs, and providing vaccinations. The fact that medical officials and medical professionals were local community leaders gradually built the locals’ trust in modern medicine and public health practices. In 1919, when the colonial government launched the cholera vaccine campaign, about 55 percent of Taipei residents received their shots with no major resistance.

In addition to this integration between the Taiwanese and modern medicine, the government also softened its approach to traditional medicine by integrating local practitioners into the public health system for primary care and outbreak monitoring.

In 1896, under pressure from the growing plague outbreak, the colonial government decided to work with practitioners of traditional medicine, who enjoyed far more trust among the local community. A new Plague Treatment Institution was established in Taipei. A Japanese physician supervised its management, but all the diagnoses and treatments carried out there were based on traditional medicine. The medical team in this treatment institution was composed entirely of locals, including practitioners of traditional medicine and their helpers. Family members of patients could stay with sick relatives in the institution.

Despite these compromises, local people initially hid from the Plague Treatment Institution. Overturning the impression that the official plague hospitals were death camps would take time. In 1899, a local newspaper reported that Japanese police had taken a Taiwanese barber into the Plague Treatment Institution because he looked sick. The barber did not have plague, and a practitioner of traditional medicine treated the illness he did have. The barber thought he would die in the institution but was shocked to learn that he could receive health care there. Thus the Plague Treatment Institution became a role model. A similar institution continued to serve patients in 1899 and 1901 when the plague resurged. In 1899, the Tea Merchant Association in Taipei established another clinic that provided health care, including traditional medicine, to the business area’s residents and migrant laborers in the tea industry if they came down with the plague.

In 1901, the colonial government further adjusted its policies by granting licenses to practitioners of traditional medicine in Taiwan. This concession was not a victory for traditional medicine, because it was a temporary compromise. The licenses were only granted at that particular moment in colonial history; no future generation would become licensed to practice traditional medicine, thus cutting off formal education in traditional medicine. Nevertheless, this policy served a significant function for public health: All traditional healers had to report cases of notifiable infectious diseases to the government. By recognizing the practitioners of traditional medicine, the colonial authority could engage these healers in the front-line monitoring for outbreaks. Through this licensing policy, practitioners of traditional medicine became part of the infrastructure of public health, providing treatment for locals and data for the government.

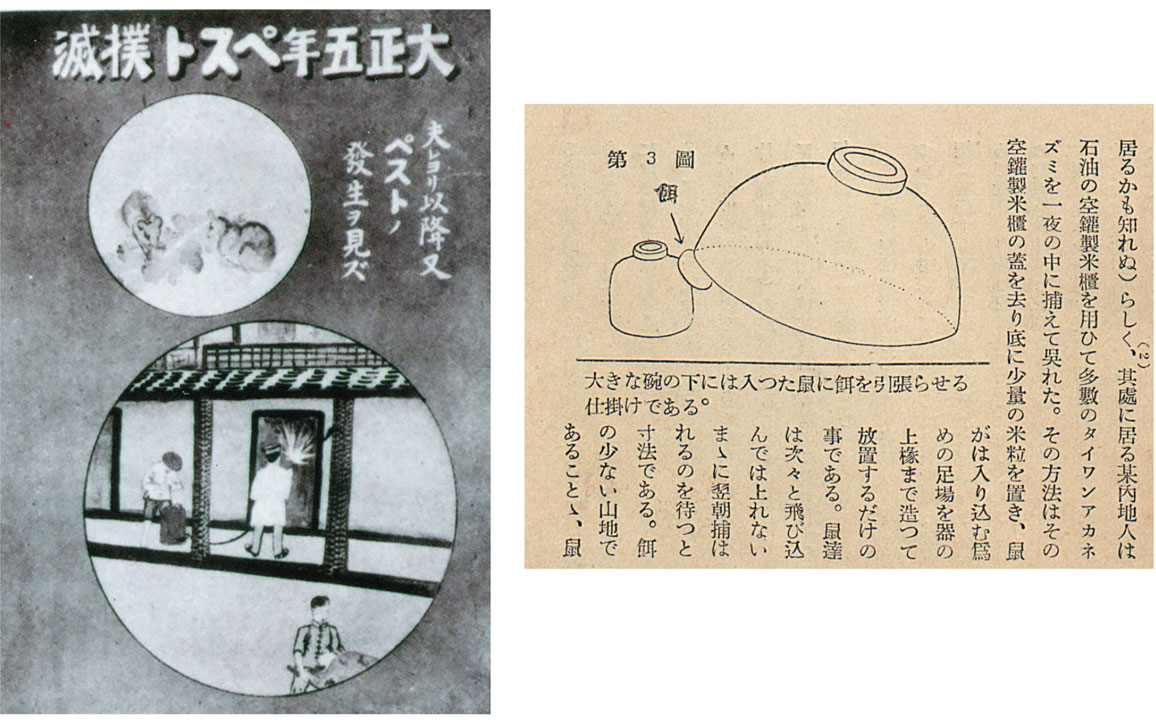

Mirror Media Inc.

Another strategy the Japanese colonial government employed was promoting alternative ways for individuals to support public health. One example was a cash award for catching mice and rats; the government would pay people to turn in the rodents, either dead or alive. This policy significantly reduced the number of mice and rats, the primary vector of bubonic plague. In the summer of 1902, there were 700 plague cases and 200 germ-carrying rats caught. These numbers peaked in the summer of 1904, with 1,600 plague cases and around 200 germ-carrying rodents. After 1907, the numbers of both patients and captured mice gradually decreased. In the summer of 1909, there were only 300 plague patients and around 100 germ-carrying mice. After that, the numbers stayed below that 1909 threshold.

Ultimately, the Japanese government succeeded in stamping out two of the most threatening diseases to the public at that time, plague and cholera, by working cooperatively with locals.

The Japanese learned from the 1896 plague pandemic that the best approach to public health is to integrate rather than oppose local traditions. Once locals could become physicians, beginning in 1899, public health systems successfully began controlling outbreaks of infectious diseases, one of the biggest threats people faced at that time. This “progressive narrative” of medicine dominates most history books. But when we look at the history of public health failure, such as that in Taiwan in 1896, we see that medical resistance was not solely about medicine or science, but rather about political and social pressure and distrust. Traditional medicine also was not relegated to the ashes of history, but rather became part of medical modernization, serving as a bridge with healing needs in local communities.

The Collections from the Archives of Institute of Taiwan History, Academia Sinica

These local healers had practiced their medicine long before the colonial government arrived, and they were there to fight with health officials over the high-profile death of one of their own Taipei residents after his vaccination, in that meeting in 1902. This position made local healers look like antiscience activists railing against modern medicine. In the “progressive narrative” of modern medicine, traditional medicine was often considered witchcraft. In fact, modern and traditional medicine have long coexisted in Taiwan.

Even though the colonial government no longer licensed practitioners of traditional medicine in the early 20th century, people still used traditional prescriptions from local pharmacies. These pharmacies were legally recognized because of the government’s business and tax concerns. Traditional pharmacies operated under licenses for pharmacists and pharmaceutical stores, and traditional healers saw their patients in these locations. In 1902, there were 125 licensed practitioners of modern medicine and 1,434 licensed practitioners of traditional medicine in Taiwan. By 1940, there were 2,302 practitioners of modern medicine and only 133 practitioners of traditional medicine, because the colonial government no longer granted licenses for traditional medicine. On the other hand, the number of traditional pharmacies increased from 173 in 1906 to 3,511 in 1922. This number later went down slightly, but there were still 2,130 traditional pharmacies in 1942. Even when the numbers of physicians increased, traditional medicine remained common in Taiwan.

Modern and traditional medicine have long coexisted on the island of Taiwan.

When the plague and cholera pandemics subsided, Taiwanese pharmacies no longer had to report cases of notifiable infectious diseases, but they still provided most of the primary care to the general population. Although the Japanese government promoted modern medical education, there was only 1 physician per 2,564 people at that time. (As a reference, there was 1 physician per 379 people in the United States in 2019.) These pharmacies filled the gap left by the lack of physicians, especially in rural areas.

The coexistence of modern and traditional medicines continues today in Taiwan. When the Republic of China government took over Taiwan at the end of World War II, it established a double-track system. Traditional and modern medicine each has its own medical education and licenses (usually the education of traditional medicine contains basic training in modern medicine, but the reverse is not the case). Modern medicine still frames public health in general, and a universal health care system monitors outbreaks. The social trust in modern medicine and the government is more solid compared with the colonial period.

Walid Berrazeg / SOPA Images / Sipa USA / Alamy Stock Photo

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Taiwan in 2019, the public health system responded quickly, directly, and transparently. In the first 140 days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Taiwan’s Central Epidemic Command Center (CECC) organized a specialized team for its COVID-19 response and held 164 livestreaming press conferences about protecting public health. These efforts are clearly trusted by contemporary Taiwanese. As of July 26, more than 91 percent of the population has received at least one COVID-19 vaccination.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, practitioners of traditional medicine worked with modern medical professionals to care for patients and prevent the collapse of the health care system. When the Omicron surge arrived in Taiwan in 2021, numbers of cases skyrocketed, and people with COVID-19 filled emergency rooms and clinics. Taiwan’s National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine launched a campaign to distribute NRICM101, which is an updated traditional prescription designed for COVID-19. Once a patient had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection and their symptoms had been confirmed by a practitioner of traditional medicine, they could apply for this prescription. Some practitioners of traditional medicine also provide health care for mild vaccine side effects, to encourage vaccination among their customers. Many also take care of patients with long COVID. Evidence about the efficacy of NRICM101 and the treatments for long COVID remains limited (although clinical trials of the former are underway), but these offerings add to the medical choices for the population.

Taiwan now enjoys high levels of vaccine uptake. This history shows that social, cultural, and political divisions that impede public health can be overcome when those in power work to learn from the marginalized, gain trust, and bridge divides.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.