This Article From Issue

January-February 2006

Volume 94, Number 1

Page 72

DOI: 10.1511/2006.57.72

The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu. Mike Davis. viii + 212 pp. The New Press, 2005. $21.95.

The 20th century is often portrayed as an era in which American medicine triumphed over infectious disease. In 1900, pneumonia, tuberculosis, diarrhea and enteritis, and diphtheria together accounted for about a third of U.S. deaths. Today, Americans are usually killed by chronic conditions that afflict us in our later years, such as heart disease and cancer. This summary, however, conceals two darker truths. First, despite the overall decline in infectious disease over the past century, there have been some dramatic disease outbreaks, most notably the 1918 flu pandemic and the current HIV epidemic. Second, much of the developing world (Cuba and Costa Rica are notable exceptions) has yet to make the transition away from infectious diseases as the leading causes of death. Such diseases are a harsh and daily reality for most of humanity.

Now the dangers of the new H5N1 influenza strain are entering the public's consciousness. As sound bites and headlines proclaim that an avian flu pandemic is imminent, thoughtful and measured analysis, and context, are needed. Mike Davis's new book, The Monster at Our Door, offers just that. Davis, an engrossing writer, provides a useful introduction to the biology of the influenza virus and to its many devious evolutionary tricks.

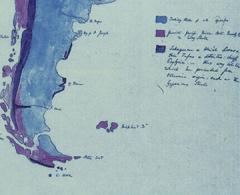

The book's main strength, however, stems from the skill with which Davis has documented the many ways in which human greed, folly and political ambition threaten our ability to respond effectively to this latest emerging infectious disease. He consistently makes unexpected connections. His account, for instance, of the rise of industrialized poultry farming in China and Thailand, driven by the increased demand for meat in Asia, both rivets and disturbs. He details how small farmers raising flocks of chickens, ducks and geese have been replaced by immense industrial conglomerates that crowd hundreds of thousands of birds in close proximity. The epidemiological implications of this transition are devastating. Previously, an infectious outbreak would be largely self-limiting, racing through a small flock and then flaming out. Now, however, conditions exist for extensive outbreaks that can quickly infect huge numbers of birds. They—and their droppings—act as sources of infection for other domesticated and wild birds. Many of the susceptible wild fowl are part of the annual migratory cycles that girdle the planet. As a result, the initial outbreaks of bird flu reported in late 2004 in Vietnam and China have quickly made their way to Siberia, Turkey and now Eastern Europe through the Danube Delta.

As Davis points out, the concentration of economic power and influence in huge poultry conglomerates militates against a rapid and rational response to outbreaks of bird flu. In chilling detail, The Monster at Our Door exposes the political pressures exerted on the government of Thailand by Charoen Pokphand (CP), the country's dominant poultry concern. These pressures have slowed the reporting of avian influenza, obstructed the monitoring of chicken and duck facilities, and limited efforts to cull infected flocks in order to prevent the spread of disease. They have also redirected the government's control measures onto the few remaining small farmers who raise chickens, often forcing them out of business and thus further tightening CP's food monopoly in Thailand. (This story of political corruption and influence is not without its surrealistic touches: In 2004, the Thai ambassador to Moscow offered to barter 250,000 tons of Thai chicken—the shipment would have begun with 60,000 tons of chicken possibly contaminated with H5N1—in exchange for Russian Sukhoi Su-30 fighter aircraft. The offer was declined.)

The specter looms in the background that in one fell swoop H5N1 could undergo antigenic shift.

The Monster at Our Door emphasizes that epidemics are rare episodes in which the delicate minuet between infectious agents and their potential hosts breaks down. If we want to understand the causes of epidemics—surely a prelude to preventing or controlling them—we must look to the ecology of hosts, vectors and agents in the broadest sense. In the case of human epidemics, that means understanding not only the ways in which the immune system sees and tracks the influenza virus but also the forces that have given rise to, say, Brazilian slums, or large-scale agribusiness in the developing world.

This broader perspective forces us to acknowledge that potentially effective antiviral agents such as Tamiflu will be of little help, given that 95 percent of the world does not have access to them. In the event that there is a worldwide influenza pandemic, Davis convincingly argues, the workings of the free market are not likely to result in optimum allocation of effort or resources. He makes this case methodically, following the money and the political ambitions that complicate our understanding of this disease and its prevention. The tone throughout is urgent but not shrill, and the book's bibliography underscores the careful research underlying Davis's arguments.

So how scared should we be? The answer is not obvious, and Davis's conclusions are necessarily speculative. The influenza virus is a formidable adversary, with a set of fiendish molecular tricks in its arsenal. Like many viruses, it has evolved replication machinery that is sloppy (unlike ours, which is uncannily accurate). This sloppiness translates into myriad versions of the viral genetic blueprint being passed on to successive generations. But there is method to this seeming madness: Each of these variants encodes a slightly different version of the virus's surface proteins. Because the immune system of a host—a chicken, an egret or a person—works primarily by recognizing the shape of the proteins on the surface of the virus, sloppy viral replication allows influenza to evade the scrutiny of the immune system. This process, antigenic drift, is akin to convicts on the lam shaving their hair or growing mustaches to keep one step ahead of the law.

But the influenza virus, by virtue of having a genome that comes in eight pieces, has an even more fiendish trick, comparable to undergoing plastic surgery: By borrowing a genome fragment from an unrelated strain, the virus can make itself virtually unrecognizable to the immune system of the host. This strategy, antigenic shift, results in a new, previously unseen type of influenza virus.

The H5N1 strain now causing concern worldwide is present in domesticated and wild birds and has seldom been seen in the human population. Thus exposure to, or vaccination against, previous strains of flu confers no protection against it. The current H5N1 strain is also unusually virulent, with mortality rates approaching 50 percent. But neither its novelty nor its virulence guarantees an epidemic. So far, H5N1 does not appear to have cracked the code for human-to-human transmission; all but a few cases are clearly the result of bird-to-human transmission. But how many mutations away is the virus from acquiring the ability to move from one person to another?

Davis points out that previous epidemics offer tantalizing but inconclusive clues to the answer. The recently reconstituted genome of the 1918 strain bears a troubling resemblance to the genome of the current H5N1 strain, although it also differs subtly from H5N1 at virtually every gene. The keys to the lethality and transmissibility of the 1918 strain lie somewhere in those differences. But no single genetic change appears to turn an ordinary flu strain into a lethal killer. We can take some small measure of comfort from the fact that multiple mutations must be present simultaneously to set the conditions for a human pandemic.

We know little about the evolutionary trajectory that results in human-to-human transmission. Genetic changes may have to occur in a specific order for the virus to survive every step of its metamorphosis into an aggressive killer. But the specter looms in the background that in one fell swoop H5N1 could undergo antigenic shift: It could acquire a genomic fragment from a strain already adapted for survival and movement in a human host and be effectively catapulted into the role of widespread killer.

Davis does an exemplary job of guiding readers through the intricacies of viral genetics, but he reminds us that the molecular basis of virulence and transmissibility is but one part of the story. We can do little to control the evolutionary excursions of the influenza genome, but we can alter the human ecology that makes pandemics possible. The Monster at Our Door is a call for human solidarity and for the internationalization of monitoring and prevention efforts.

As Davis emphasizes, the notion that the influenza pandemic can be stopped at our country's borders and the belief that American medicine is a sufficient bulwark against such a threat are unsupportable. Ultimately, the irony of the early 21st century could turn out to be the return of infectious diseases, old and new, as the prevailing threats to human survival. It will take what is best in our species—solidarity, inventiveness and cooperation—to keep the past from becoming the future.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.