Seeds on Ice

By Cary Fowler

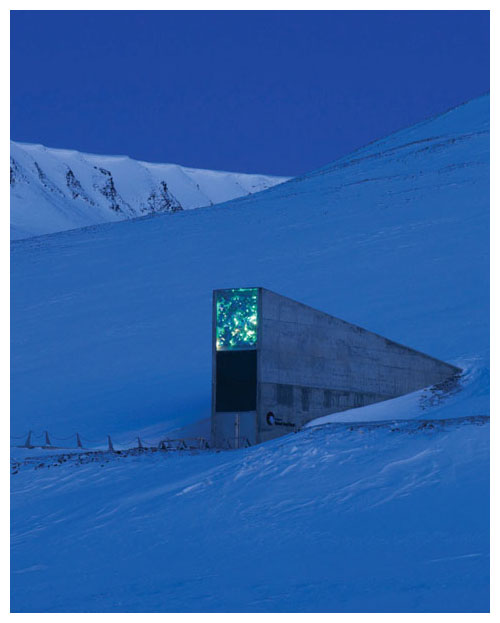

In the Arctic Circle, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is not waiting for doomsday, but is a secure backup for crop diversity.

In the Arctic Circle, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is not waiting for doomsday, but is a secure backup for crop diversity.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.122.304

Closer to the North Pole than to the Arctic Circle, remote and rocky Plateau Mountain in the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard seems an unlikely spot for any global effort, much less one to safeguard agriculture. In this frigid and dramatically desolate environment, no grains, no gardens, no trees can grow. Yet at the end of a 130-meter-long tunnel chiseled out of solid stone is a room filled with humanity’s most precious treasure, the largest and most diverse seed collection ever assembled: more than a half-billion seeds.

A quiet rescue mission is under way. With growing evidence that unchecked climate change will seriously undermine food production and threaten the diversity of crops around the world, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault (above) represents a major step towards ensuring the preservation of hundreds of thousands of crop varieties. This is a seed collection, but more importantly it is a collection of the traits found within the seeds: the genes that give one variety resistance to a particular pest and another variety tolerance for hot, dry weather. Plant breeders and farmers will draw upon this diversity to help crops keep pace with a warmer climate and ever-evolving pests and diseases. Virtually everything, every trait we might want our crops to have in the future, can be found in this genetic diversity.

Few people will ever see or come into contact with the contents of this vault. In sealed boxes, behind multiple locked doors, monitored by electronic security systems (not to mention the occasional visit from indigenous polar bears), enveloped in frigid, below-zero temperatures, and surrounded and insulated by tons of rock, hundreds of millions of seeds are protected in their mountain fortress. Frozen in such conditions inside the mountain, seeds of most major crops will remain viable for hundreds of years, or longer. Seeds of some are capable of retaining their ability to sprout for thousands of years.

As of the fall of 2015, after just seven years of operation, samples of more than 880,000 crop varieties or populations are being preserved, from virtually every country on Earth. That’s about 500,000,000 seeds, some 40 tons. A simple single-spaced listing of all the crops in the Seed Vault would run 55 pages long. And yet, more seeds are on their way to Svalbard.

Most seeds are packaged in heat-sealed, laminated, moisture-proof, air-tight foil packages. The packets are stored inside boxes. Typically, 400 to 500 samples with about 500 seeds each fit in a box, depending on the size of the seed. Thus far 2,291 boxes have been shipped to the Seed Vault. When the first vault room is filled with close to 1.5 million samples, about the maximum number of distinct varieties we think exist, it will contain nearly a billion seeds with a weight approaching 80 tons.

Everyone can look back now and say that the Seed Vault was a good and obvious idea, and that of course the Norwegian government should have approved and funded it. But back in 2004, when the Seed Vault was proposed, it might equally have been viewed as a crazy, impractical, unnecessary, and expensive idea, another grand government folly. Government administrations the world over are risk averse. A room for storing seeds inside a mountain near the North Pole? Are you kidding? Norway said yes.

We knew that nothing we could conjure would provide an ironclad guarantee. Such guarantees don’t exist in the world. But we were tired, fed up, and frankly scared of the steady, cumulative losses of crop diversity. We were in problem-solving mode. The Svalbard Global Seed Vault was built by optimists and pragmatists, who wanted to do something to preserve options so that humanity and its crops might be better prepared for change. We don’t need to experience an apocalypse for the Seed Vault to be useful. If the Seed Vault simply resupplied seed genebanks with samples those genebanks had lost, this would repay our efforts and the costs a thousandfold.

The Seed Vault is about hope and it is about commitment—about what can be done if countries come together, shed suspicion and cynicism, and work cooperatively to accomplish something significant, long-lasting, and worthy of who we are and wish to be.

Open the heavy locked metal entrance door to the portal building of the Seed Vault, and the length of the tunnel becomes visible. The surface layer of rock is loose, the result of freezing and thawing for millennia, so the beginning of the tunnel is encased in heavy steel tube ( left ). Beyond this shallow, unstable, and fragmented layer of rock and soil, the permafrost area begins and the rock is solid. Visitors instantly observe that the Seed Vault is not a pristine, antiseptic laboratory. It was not designed as a research facility or a tourist attraction. It’s a pratical facility all about freezing seeds. Pipes overhead carry cold air to the farthest reaches of the facility where the seeds are stored. Past the steel-tube section, the tunnel transitions to rock, spray coated with a layer of white plastic-fiber-impregnated concrete. It’s a bright tunnel, but austere. Having a facility that virtually operates by itself, without exposure to too many human interventions or potential mistakes, that does its job even if the mechanical cooling goes on the blink—all these factors are key to having a Seed Vault that functions properly over the long term, is secure, and is economically sustainable.

There is a set of closed, locked double doors at the very end of the tunnel. Open these and you enter an awe-inspiring, cavernous room in the heart of the mountain, a huge and colder room with tall ceilings coated with millions of tiny glistening ice crystals (right ). I have always thought of this as the “cathedral room.” It lies at right angles to the tunnel and serves as a staging area for preparing boxes to go into the frozen vault room. The three vault rooms lie on the far side of the cathedral room. Two lie to the left of the tunnel shaft, one to the right. The layout is purposeful. None of the vault rooms are situated in a direct line down the tunnel from the entrance. Instead, at the architect’s behest, the workers carved out a concave indentation in the rock as a security measure. Were there to be any explosion inside the facility, this feature would direct the shock waves back out the tunnel, diverting them from the vault rooms on either side.

The seed storage vault rooms are located both where the natural temperature was coldest and where the quality of overhead rock was the best for structural integrity. Each of the three vault rooms is approximately 27 meters long, 9.5 meters wide, and 5 meters high. Only one room is currently needed and in use ( left ). We might discover that seeds of some crops are best conserved at a different temperature than the standard –18 degrees Celsius provided, which would indicate the use of one of the other rooms cooled to a different temperature. |

Seed collecting did not begin with the Seed Vault. In fact, the Vault has never been involved with gathering seeds directly from the field. In the 1970s agricultural scientists sounded the alarm that the wave of modern seed varieties sweeping across the world was massively displacing traditional varieties and driving them into extinction. Today there are 1,700 collections of crop diversity. In total, these genebanks house more than 7 million samples, up to 1.5 million of which are thought to be distinct. In the early 1990s I oversaw the United Nation’s first comprehensive global assessment of the state of the world’s crop diversity. What my small team and I found was shocking. The “global system” of genebanks was no system at all. There were a handful of effective facilities. Even the best genebanks, however, were often succeeding solely because of the heroic action and dedication of their unsung staff. How long was the world willing to rely on such luck? If this was plan A, what was plan B? We needed one, fast. And this is a big reason why having a safe “backup copy” in a place like Svalbard is so critically important.

The Vault now contains, for example, a sizable collection from the U.S.-based Seed Savers Exchange, the largest organization of gardeners working to conserve heirloom vegetable varieties (its members are shown at an heirloom tomato tasting at top right, and some of its tissue culture conservation techniques for heirloom potatoes are shown second from top).

It is difficult to estimate how much crop diversity exists in the world today, and impossible to know how much has been lost. In the fields of many traditional farmers, there are few “uniform” varieties wherein all plants are essentially identical. A wheat field may contain a number of different types, maturing at different times, with different degrees of pest and disease resistance ( below ).

|

As fighting broke out in Tunisia and elsewhere in what is now called the Arab Spring, I got on the phone with my old friend Mahmoud Solh, the director general at the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), then based in Syria. Mahoud and I agreed that Syria, and the ICARDA collection, would likely escape the turmoil. (How wrong we were.) But I suggested to Mahmoud that we should try to get a duplicate copy of his collection up to Svalbard as soon as possible, just in case. ICARDA was able to get seeds of virtually everything up to Svalbard—116,000 different varieties, more than 58 million seeds. In early September 2015, ICARDA requested the return of seeds from its duplicate stores in Svalbard ( sample seeds shown at right ). On September 23, 128 boxes of seeds, samples of 38,073 varieties of wheat, barley, lentil, chickpea, faba bean, grass pea, and a number of samples of crop wild relatives and forages were sent to Morocco and Lebanon, where ICARDA is reestablishing working genebanks. This first withdrawal of seeds is bittersweet. Everyone hopes this will be the last time the Seed Vault will be used for the purpose for which it was established. But I know it won’t be. |

This article is excerpted and adapted from Seeds on Ice: Svalbard and the Global Seed Vault by Cary Fowler. © 2016 by Cary Fowler. Photographs by Mari Tefre and Jim Richardson. Introduction by Sir Peter Crane. Published by Prospecta Press.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.