This Article From Issue

May-June 2021

Volume 109, Number 3

Page 182

ATOMIC DOCTORS: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age. James L. Nolan, Jr. 294 pp. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. $29.95.

For many years I have shown my students a curious memento of the mid-20th century: a Western Union telegram that was used to transmit top secret information. Dated November 30, 1945, it was sent by Robert M. Fink to “Dr. Wright Langham c/o D. L. Hempelman [sic].” In its entirety it reads “H.P.-3 AND H.P.-4 INJECTED TUESDAY, NOVEMBER TWENTYSEVENTH. H.P.-5 INJECTED FRIDAY, NOVEMBER THIRTIETH."

To begin to decode this message, one would have had to know the occupations of the sender and recipients: Robert M. Fink was a physician at the University of Rochester’s Strong Memorial Hospital, where the toxicity of radioactive isotopes was being studied; Wright Langham, a chemist, led the Biological Research Division at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where a nuclear weapon was being secretly developed as part of the Manhattan Project; and Louis Hempelmann was a physician and director of the Health Group at Los Alamos. “H.P.” was an abbreviation for the disconcerting term human product. Human products 3, 4, and 5 were patients at Strong Memorial, and they had been injected with plutonium without their consent as part of a highly sensitive experiment to determine the effects of the new element on the human body. Fifteen additional patients were subjected to the experiment at other hospitals—at the University of California, at the University of Chicago, and in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. All four locations were Manhattan Project sites.

This shocking experiment was motivated by worries about the safety of the laboratory workers at Los Alamos, but the U.S. government’s willingness to expose unwitting Americans to dangerous radiation without their consent is appalling. Thus it is unsurprising that the legacy of this and other radiation experiments carried out during World War II and the Cold War has proved vexing for the government. The experiments were covered up for decades. Rumors about the plutonium injections nevertheless persisted; then in the fall of 1993 the Albuquerque Tribune began publishing an investigative series by reporter Eileen Welsome titled “The Plutonium Experiment,” which later won a Pulitzer Prize. Word of Welsome’s reporting reached President Clinton’s Secretary of Energy, Hazel O’Leary, who brought it to the president’s attention. He then appointed an Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments (ACHRE), for which I served as a staff member. The ACHRE produced a thousand-page report based on 18 months of intensive investigation, during which tens of thousands of pages of classified documents, including the aforementioned telegram, were examined and became part of the ACHRE record. The report concluded that the federal government had engaged in experiments that were wrong even by the standards of the day and had in some cases resulted in demonstrable harms that were not disclosed.

Now James L. Nolan, Jr., has written a book—Atomic Doctors: Conscience and Complicity at the Dawn of the Nuclear Age—that provides an admirable account of the central role of physicians in the Manhattan Project and its aftermath. He makes use of many of the old documents that were available to ACHRE in the mid-1990s. But he also has access to a source that was unavailable to us: notes made by his grandfather, James F. Nolan, who along with Hempelmann was one of several physicians in charge of the medical care of the thousands of residents of Los Alamos, the city that was created for the express purpose of building the Bomb. Hempelmann's and Nolan’s assignments went well beyond the provision of routine medical care. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was scientific director of the Manhattan Project, wanted them also to monitor Los Alamos lab workers for radiation exposure, because he was aware of cases in which excessive exposure to ionizing radiation had been harmful to people, including Marie Curie, health care workers who developed leukemia from working with x-rays, and women factory workers who applied paint containing a small amount of radium to watch dials to make them luminous.

Hempelmann and several colleagues from the Metallurgical Lab at the University of Chicago modeled their safety operation on the safety measures that eventually had been implemented at the watch factories. However, conditions at Los Alamos did not match those in the factories, not least because the material being used was plutonium (whose effects on the body were less well understood than those of radium) and the operations being carried out were far more complicated than watch painting. As the work proceeded at Los Alamos, both the workers and the members of the Health Group insisted on stricter conditions. Even in that far less litigious era, the doctors worried about their potential legal liability.

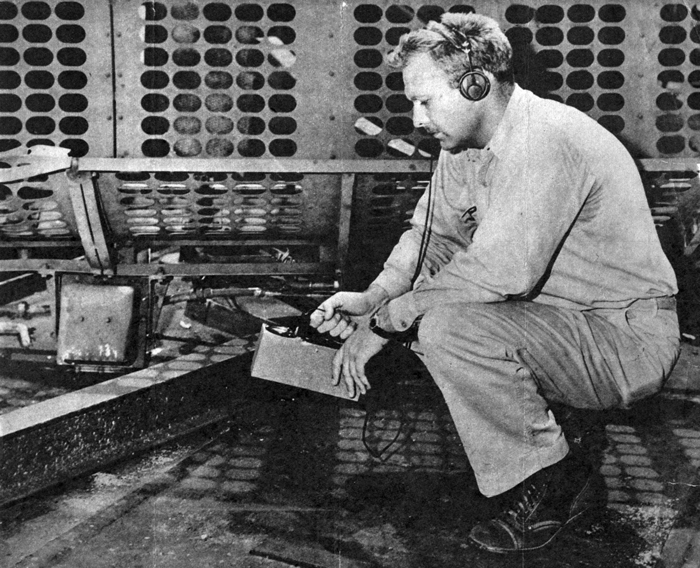

From Atomic Doctors

Atomic Doctors is no mere family memoir. Nolan’s skillful weaving of his grandfather’s story into an account of the pressures exerted on medical ethics by time, place, and circumstance makes for compelling reading. Nolan, who is a sociologist, shrewdly notes the distinctive ethos of each of the three communities at Los Alamos. The military, led by the ruthless, egotistical, whip-smart General Leslie Groves, wanted to build a nuclear weapon before Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, or the Soviet Union could do so. The scientists, led by the brilliant, philosophical, somewhat naive Oppenheimer, wanted to know whether their theories would be borne out in this engineering project. And the physicians, led by Hempelmann, were torn between a mission of healing and protection and the momentum of the massive weapons development organization of which they were a part. Ultimately the physicians succumbed to that momentum, and security, secrecy, and speed superseded health concerns.

Nolan does not spare his grandfather a moral reckoning. But before reaching that assessment, he makes superb use of James F. Nolan’s descriptions of his role in a series of events that unfolded after his sojourn in Los Alamos ended. First we are treated to a gripping reconstruction of the transport of a massive lead canister of uranium-235 from Los Alamos to Albuquerque to San Francisco to Tinian Island. Along with a colleague, Dr. Nolan accompanied the U-235 in the guise of an artillery officer to maintain maximum security. (Nolan knew not the first thing about artillery, however, and in one somewhat comical scene he makes an unconvincing stab at persuading a couple of officers that he is an expert.) Their cargo was a portion of the core explosive material used to fuel “Little Boy,” the bomb that was loaded onto the Enola Gay on Tinian Island and then dropped on Hiroshima.

Nolan’s atomic odyssey did not end there. In the weeks that followed, during the American occupation of Japan, he was a member of one of several teams that were assigned to investigate the residual radiation effects of the atomic attacks on civilians—effects that the experiment with plutonium injections would not necessarily illuminate. The team from the Manhattan Project, which included physicist Philip Morrison, was merged with two other groups to form the Joint Commission for the Investigation of the Effects of the Atomic Bomb in Japan. The Manhattan Project’s participation in the investigation, which lasted only five weeks, was later characterized by journalist Daniel Lang, who interviewed Morrison about it, as “an unusual mixture of tourism, scientific exploration, and public relations work.” Groves and others pressured team members to minimize the medical consequences for survivors in an attempt to avoid creating a hostile reaction to the bombing at home and abroad. Hempelmann, who wasn’t included on the team that went to Japan, was drawn into this public relations vortex when Groves and Oppenheimer brought reporters to the Trinity Site in New Mexico (where the first nuclear detonation had taken place) and falsely claimed that the area was free from dangerous levels of residual radiation. Concerns about residual radiation danger haunted at least some of the physicists, including Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, and Albert Einstein.

The Marshall Islands were the last stop on Nolan’s atomic odyssey. In 1946 he came to the Bikini Atoll, where the atomic tests of Operation Crossroads were to be carried out in an attempt to settle the question of whether armies and navies were even needed anymore in the atomic era; the notion that they might not be necessary was being propagated by the emerging air force, led by the aggressive General Curtis LeMay. In a reckless exercise of interagency competition between the Army and the Navy, nuclear detonations were going to be used to test the effects of atom bombs on naval vessels. The residents of the Bikini Atoll were persuaded to leave their island homes before the bombing began, but they thought that their relocation would be temporary; no one told them that the atoll would be rendered uninhabitable, and they were never justly compensated. The book explains that they, along with other Marshall Islanders, were outrageously exploited.

As a radiation safety officer, Dr. Nolan was part of a team that assessed the dangers that the targeted naval vessels would pose if boarded after a detonation. After the blasts, he found high levels of radiation, but his findings were downplayed. So began a decades-long push and pull between health physicists and military leaders about what should be labeled the maximum tolerable dose of radiation. The risks were nearly always underestimated, despite the fact that the level of exposure deemed medically acceptable was repeatedly lowered drastically. One of the main purposes in having doctors record radiation levels appears to have been to create a paper trail that could be helpful in denying any future legal claims that might be brought against the government. Operation Crossroads was followed in 1948 by Operation Sandstone, in which three more bombs were dropped on the Marshall Islands, and by 1958 the United States had conducted another 62 bomb tests there.

From Atomic Doctors

After participating in Operation Sandstone, James F. Nolan was more than happy to resume his profession as a civilian obstetrician-gynecologist with a special interest in applying nuclear medicine to cancer therapy. But what he had done and seen, especially in the nightmarish landscape of postwar Japan, was never far from his mind. In a 1971 lecture, after stressing that he had not developed serious medical problems from his numerous exposures to radiation, he emphasized that physicians had an obligation to take radiation risks for improved patient care, and he made a disparaging remark about the emerging emphasis on informed consent. These comments are chilling, because they bring to mind the rationalizations of other medical experimenters who have continued to resist reforms in ethical practices.

What, in a moral sense, are we to make of James L. Nolan’s atomic medical career? Historians and philosophers struggle with the pitfalls of “retrospective moral judgment,” a form of ethical anachronism. Unquestionably, World War II was a national emergency, and a Nazi victory in the race for the Bomb would have been a disaster for human civilization. Nevertheless, carried forth by a vast institutional momentum, most of the Manhattan Project protagonists persisted even after that danger had passed. The destructive force of this killing technology seared the souls of those who, like Nolan, saw the results in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the weeks after the bombs were dropped. Was James F. Nolan a good man, caught in a maelstrom of extraordinary times, who responded to a call to national service but was finally swept up in circumstances that few of us could have transcended? (He did, after all, provide some care to Japanese victims.) Or was he an ambitious young professional with a sense of adventure who saw remarkable career challenges and opportunities unfolding and resisted any prods of conscience? We know that he felt relief at leaving the military so that he could turn to using radiation to heal people in his medical practice, but beyond that, his internal moral journey remains opaque to the reader—and, it appears, to his grandson, who opts for a different approach to questions of morality.

Near the end of the book, Nolan examines his grandfather’s role through the lens of French sociologist Jacques Ellul’s philosophy of technology, in which the modern notion of technique is taken to be driven by a quest for efficiency. Since the dawn of the Atomic Age, that quest has had its optimistic advocates—including, in our own time, Raymond Kurzweil. But pessimists such as Oppenheimer see technology as not only irresistible but also finally destructive. As the decades have passed, Ellul’s description of nuclear technology as a “whole package” whose benefits cannot be separated from its difficulties (particularly the necessity of storing massive quantities of nuclear waste) has come to seem increasingly apt. Nolan extends this view of technology as inherently destructive from the atomic bomb to gene editing, which some readers may find a stretch, though bioethicists such as Daniel Callahan have made quite similar arguments about the technological imperative.

Throughout the book, the reader encounters details and descriptions that pack a moral punch. I was particularly struck by Nolan’s account of a conversation that took place in Japan in 1945 between Morrison and Masao Tsuzuki, a distinguished surgeon who had been a student at the University of Pennsylvania. The sardonic Tsuzuki handed Morrison a copy of his 1926 paper on the effects of radiation on laboratory animals. “After Morrison scanned and returned the document,” Nolan writes, “Tsuzuki slapped the American physicist on the knee and said, ‘Ah, but the Americans—they are wonderful. It has remained for them to conduct the human experiment.’”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.