A Biting Buzz

By Fenella Saunders

Bees transfer vibrations better and increase pollen rewards when they grasp flowers with their mandibles.

Bees transfer vibrations better and increase pollen rewards when they grasp flowers with their mandibles.

A tasty pollen reward comes from flowers that bees visit. If the bees shake the anthers, the part of the flower that holds the pollen, do they get more out? “In a similar way to shaking a ketchup bottle, vibrating the anthers speeds up the release of pollen,” says Charlie Woodrow, an ecologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. But maybe flowers have evolved shapes to limit how much pollen bees can take in one sitting. Woodrow and his colleagues decided to see if they could delve into this sort of morphological arms race between bees and flowers.

All images from C. Woodrow et al., Current Biology 34:4104–4113.e3, CC-BY.

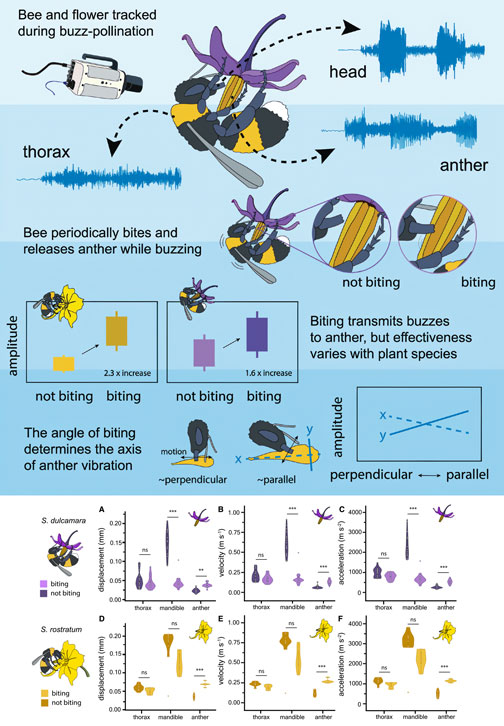

About half of the world’s 20,000 or so bee species use a process called buzz pollination, in which the bee curls its body around the anthers and emits short, rapid bursts of vibration. And tens of thousands of plant species have coevolved to require this specific behavior in order to induce the release of their pollen—lower amplitude vibrations such as from wind gusts won’t do it, Woodrow explains. The vibration was thought to transfer to the flower primarily through the bee’s body contact.

Researchers also knew that buzz-pollinating bees often hold onto anthers with their mandibles, and thought that this biting was likely to prevent the bees from being shaken off the flower during the vibrations. But the bees don’t constantly hold onto the anthers with their bites—they do a quick pattern of biting and releasing while they buzz. Woodrow and his colleagues wondered why the bees would let go if the purpose was to stabilize themselves.

Buzzing is an acoustic behavior, but Woodrow and his colleagues figured out that the most reliable method to measure the vibration of the bee and the flower simultaneously was visual, with high-speed video, which avoided the need to contact the bee during the behavior. To make measurements, Woodrow hand-marked a miniature scale on each of the approximately 100 flowers that the team used. “I tried having a ruler in the image, but the problem is, when the bee is on the flower, it swings the flower back and forth, so the error on the measurement becomes much larger. So I thought, if we can have the scale actually on the flower, then we know that the change in that scale with distance is going to have a much smaller effect on how we interpret the data.” The team was then able to convert the displacement of the bee and the flower in the video into a measurement of vibration.

The video allowed Woodrow and his colleagues to isolate the vibration level at the bee’s head and body, as well as at the anther, all at the same moment. Their data showed that biting the anther caused significantly more vibration than buzzing alone, and that the mandibles vibrate much less during biting (see graphic below). “That finding suggested to us that this biting and non-biting pattern is the way that the bees are transmitting the vibrations,” Woodrow said. “It’s not just a way to hold on to the flower.”

C. Woodrow et al., Current Biology 34:4104–4113.e3, CC-BY.

The team used bumblebees (Bombus terrestris) as an example bee species, and two different flowers, Solanum dulcamara (commonly called Bittersweet) and Solanum rostratum (known as Buffalo bur). Both flowers are known to need buzz pollination, but their shapes are quite different: The former is more cone-shaped and hangs downward, whereas the latter is larger, flatter, and more open. The team wanted to investigate whether the differing shapes would modify the ways that the bees interacted with the flowers. Their data showed that the biting behavior was more effective with S. rostratum, increasing the amplitude of vibration 2.3 times, versus 1.6 times with S. dulcamara.

The reason for this difference seems to come down to the morphology of the plant, because the angle that the bee can attach itself seems to be the limiting factor in an efficient transfer of buzz. “If the bee is biting perpendicular to the flower parts, then when it’s vibrating the flower, it’s essentially pulling on the entire flower,” Woodrow explains. “But if it bites closer to parallel, then it shakes the flower across an axis that has more freedom of movement, which should in theory release more pollen.” The hanging S. dulcamara seems to be difficult for the bees to attach to in a parallel direction, and that appears to cause a slower pollen release. The larger, more laterally angled S. rostratum makes it easier for the bees to get a strong parallel grip, releasing the pollen faster (see video below).

C. Woodrow et al., Current Biology 34:4104–4113.e3, CC-BY.

And it may be an advantage to the flowers to decrease the reward the bees receive. “Not only does it limit the amount of pollen the bee can take, so it doesn’t overexploit the flower, but also it increases the time that the bee is in contact with the reproductive parts of the flower to transfer pollen from the last flower it was on,” Woodrow says.

The question remains as to why the bees have this bite-and-release pattern on the flowers. Woodrow thinks it could be for several reasons, which may also vary by the type of flower: “One reason is the energetic cost; it’s difficult to maintain holding onto the flower because they’re using their muscles to move the mandibles as well. Another may be so that the bee could move between different parts of the flower: Maybe it’s using a behavior referred to as anther milking, in which the bee starts at the top of the flower and moves down during the course of a buzz, which might help to release the pollen further. Another suggestion is what we call the bellows hypothesis, which might work in hanging flowers. If you just squeeze the flower without the bee, the pollen comes out. Maybe by biting and not biting they can force the pollen out through two different mechanisms, which should increase the speed that they can acquire this resource.” Woodrow and his team plan to use artificial vibrations, either continuous or with a start-stop pattern, to count how much pollen is released, which may help determine the answer.

Better understanding this widespread pollination behavior could help a large number of bee species, many of which have seen their populations in steep decline recently. Because half of bee species are buzz pollinators, habitat loss and decrease in biodiversity may limit the options for affected bees and flowers. “Maybe there are some really exclusive couplings in which one bee species requires one buzz-pollinated flower, or vice versa,” Woodrow says. “If we know this, then these habitats are the places we can focus conservation efforts.”

Buzz pollination also occurs in food crops, including tomatoes, potatoes, blueberries, and kiwifruits, which can only be pollinated by bees. Woodrow and his colleagues are exploring whether it’s possible to artificially emulate the buzz pollination process, to supplement declining bee populations. “If we understand the way that bees are holding the flowers, maybe we can develop microrobots that can do similar things,” Woodrow says.

To find out more, Woodrow hopes to move beyond bumblebees and take high-speed video of a wide range of wild bee species on flowers. “Bumblebees are so fluffy, it’s really hard to track anything on them,” he explains. “Some orchid bees, for example, are super reflective, which would make a really nice video.” He plans to mark up a lot more flowers next summer. “We will test our work by bringing some of our greenhouse plants into the botanical garden here, where we have lots of different bee species flying around, and then see if anything visits and try to get some good videos,” he says. “We just have to sit and wait and watch a flower for many hours.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.