This Article From Issue

November-December 2021

Volume 109, Number 6

Page 378

GRAND TRANSITIONS: How the Modern World Was Made. Vaclav Smil. xi + 363 pp. Oxford University Press, 2021. $34.95.

Asked to name the disruptive technologies that have shaped the modern world, most people might mention the internet, airplanes, the internal combustion engine, or the printing press. But Vaclav Smil chooses to focus on the technologies that have improved our ability to extract food and energy from the planet’s biosphere—an ability that underpins humanity’s existence. Technologies that can produce abundant food produce a small component of the gross domestic product in industrialized economies, but they are a defining feature of the modern world, as are the technologies that enable energy to be extracted from the long-buried biomass of fossil fuels. In his latest book, Grand Transitions, Smil explains that the modern world—the one that began to emerge around 1500 CE—arises from the interactions of transitions in agriculture and energy with transitions in populations, economies, and environments.

Smil has published dozens of books dealing with this subject matter; four of them examine “long-term transformations of global food production and nutrition,” four others deal with energy resources and uses, another five are about “key technical and material inputs of modern economies,” and three more focus on the global environment. These books are unapologetically chock-full of detailed facts and statistics, to the point of data overload. This latest book is no different; the reader must wade through data showing trends in birth and death rates in country after country, the application rates of nitrogen, and the proportion of daily calories a person gets from cereals. Grand Transitions is classic Smil; that is to say, it is the product of deep research.

Smil organizes the book by megatrends. He focuses successively on sweeping changes in family structures, the way people get food, how they use energy, and how they work. The first chapter describes the five types of interdependent epochal transitions—in populations, agricultures and diets, energies, economies, and the environment—and lays out the chronology of those transitions in various places. Smil emphasizes that for most of human history, in the premodern world that existed before the 16th century, sons and daughters experienced the same living standards as their parents. But in the modern world, change occurs within the time frame of a single generation.

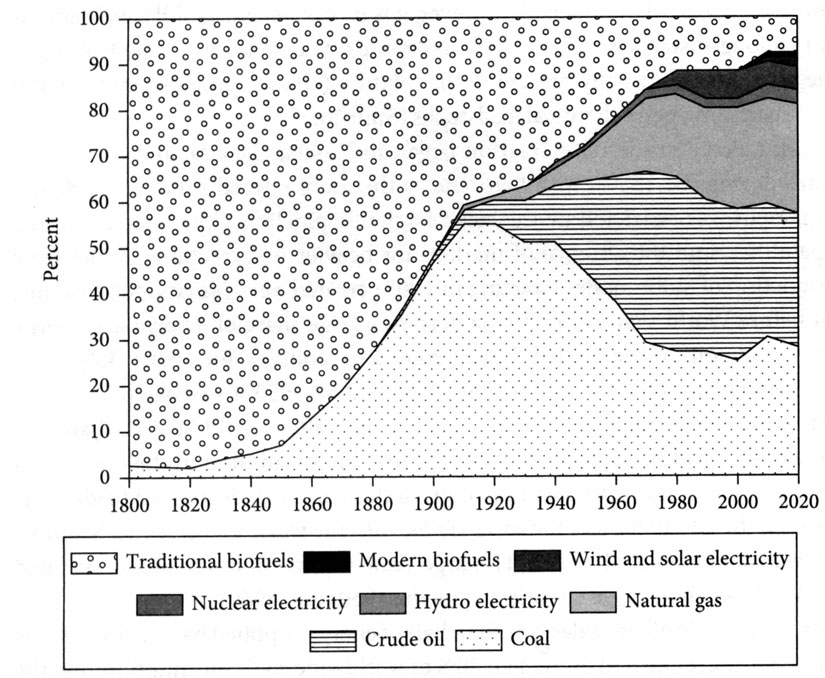

Subsequent chapters provide data from countries around the world that capture the marked accelerations that have taken place. Death rates have fallen with the introduction of sanitation and other public health measures, and fertility rates have declined. In agriculture, yields have risen and labor requirements have fallen; diets have become less starchy and richer in animal-sourced foods. The amount of energy available for travel, industry, and residences has increased massively, first as animals replaced human labor and then as fossil fuels replaced animal labor.

From Grand Transitions

All of these grand transitions have been encapsulated in structural changes in economies, which are the subject of a separate chapter. Graphs that trace the number of workers employed respectively in agriculture, industries, and services depict the fundamental transition that has occurred in many countries and is in progress in others. S-shaped logistic curves of gross domestic product over time illustrate the reality that economic growth has its limits.

The chapter on economies is followed by one on the environment, which takes the reader on a dizzying tour through the many environmental insults that the modern world has inflicted on the biosphere, from deforestation and subsequent reforestation, environmental pollution, and nitrogen runoff to climate change. In premodern societies, people used fire to clear land and decimated megafauna, but the impact of the modern world on the biosphere has been massive.

Grand Transitions doesn’t entirely succeed in fulfilling the implied promise of its subtitle—it doesn’t actually explain How the Modern World Was Made. The statistics with which the book is packed are necessary to capture the arc of human progress, but statistics don’t suffice as an answer. A more fitting subtitle might have been A Chronicle of Trends Leading to the Modern World, or All the Facts You Need to Try to Make Sense of the Complex Modern World.

Smil argues persuasively at the book’s outset that it simply is not possible to decipher clear cause-and-effect relationships in the transitions that propelled humanity as hunter-gatherers became agriculturalists and then urban dwellers in postindustrial economies. Did the expansion of cities result from technologies that created surplus labor in the countryside, or vice versa? Did a shortage of wood spur the Industrial Revolution, or did the economic advantages of coal-powered technologies underlie that transition? In postindustrial societies, will an increase in the proportion of the population made up of elderly people have the effect of reducing the demand for food? Will the purchase of convenience food and take-out food continue to increase? We don’t know, Smil admits. “Simplifications are always perilous,” he tells us, and he cautions that “another strong argument against generalizations” is the “unpredictable course” of many transitions.

Yes, demographics have changed; rates of birth and death that were once high have dropped. Urbanization, technologies that have increased agricultural production, advances in public health, and new energy sources have enabled previously unthinkable advances in mobility, industry, and everyday life. All of these factors have intersected to make the modern world. Structural transitions in economies from agricultural to industrial to service-based have both promoted and been promoted by these myriad transitions. But to achieve a deeper understanding of this complexity, one must journey beyond the comfort zone of a natural scientist. Grand Transitions does not delve into the influences of colonial legacies and power dynamics on the ways people have relied on products of the biosphere. Smil doesn’t unravel the profit motive as a force that has influenced the massive increase in food production and the unceasing extraction of energy resources, nor does he examine the roles that family planning and opportunities for women have played in demographic transitions. He gives short shrift to the ability of societies to modify the laws, regulations, and cultural expectations that govern use of the biosphere.

It is unreasonable to expect a book to tidily encapsulate the vast ecological, political, and social forces that have shaped the modern world. Grand Transitions does provide an overview of the trends and pivot points in different countries. But the story is incomplete, because Smil doesn’t dig into the decisions, cultural changes, economic settings, and ecological conditions that have collectively shaped these transitions in health, food and energy supplies, living standards, and opportunities for mobility and employment in societies around the world. Given the rapidity with which transitions are occurring along the future’s untrodden and uncertain path, useful analyses of the past must take a more holistic view.

The book’s final chapter is titled “Outcomes and Outlooks.” Smil strikes an even tone here, despite his pessimistic outlook on the environment. He reiterates that impressive and undeniable, though unequally distributed, progress has occurred over the past century in health, education, access to information, and living standards. He does not buy into dystopic predictions of the downfall of modern civilization, citing former predictions of population explosions, famines, energy shortages, and economic collapse that have failed to materialize. But he also does not adhere to the wishful thinking of techno-optimism, nor does he assume that progress will be unending. He challenges the conclusions of Hans Rosling and Steven Pinker, who have cited past progress as proof that improvements will continue.

In the book’s final pages, Smil returns to his main message, that regardless of the modern world’s seeming sophistication and technological prowess, the biosphere sets the parameters. “Any serious historian must acknowledge that we have been a very adaptable, a very inventive, and hence a very successful species—but surely not a godlike one,” he writes. The future remains unpredictable and humanity’s destiny unknowable, but the foundation for a promising future is a healthy biosphere. To have any hope of such a future, humans must make decisions that curtail outcomes to the contrary.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.