Cancer Nanomedicine

By Patrick Couvreur

Serendipity and unexpected observation lead to new concepts.

Serendipity and unexpected observation lead to new concepts.

Throughout my scientific career since the mid-1970s, serendipity has played an important role. A failure may have a significant effect on the outcome of an experiment, but the mind must remain open and prepared to seize the opportunity of an unexpected observation. One such failure in my laboratory, in which we were unable to encapsulate a particular anticancer drug into nanoparticles, resulted in an entirely new nanomedicine concept. Because we didn’t give up, our continued effort led to this unexpected discovery.

I have been involved with nanomedicine since its early days. My PhD work, at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium, was on pharmaceutical technology and examined the mechanisms of how tablets disintegrate in the body. However, my laboratory happened to be next to that of Christian de Duve, who had won the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1974 in particular for the discovery of lysosomes and their role in degrading material taken up in the cell. I would sometimes discuss my work with some of the researchers in de Duve’s laboratory over lunch. Their opinion was that I should concentrate on “minitablets” for delivery of medications into cells rather than on tableting. This talk gave me the general idea of developing a “nanopill” that would allow drugs that normally are not able to diffuse into a cell to nonetheless gain access with a carrier.

I soon after read a pioneering article by Peter Speiser and his colleagues at ETH Zurich which described “nanoparts,” polymerized micelles made from the chemical acrylamide, pulled together into a capsule shape that can enclose other substances. Speiser’s polymerized micelles were intended to be used as immune enhancers, because they could release encapsulated antigens over a long period of time. I was able to undertake a postdoctoral project with Speiser that aimed to encapsulate anticancer compounds in these nanocapsules and test their ability to release their drug payload intracellularly.

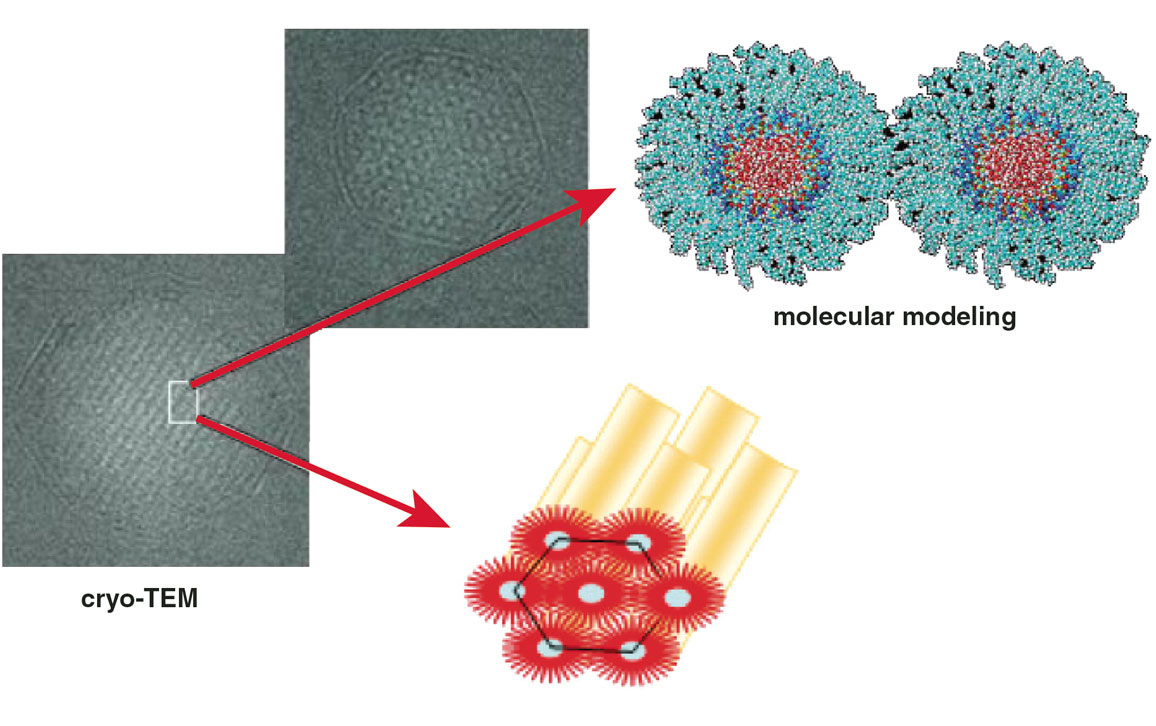

Adapted from P. Couvreur et al., 2008, Small 4:247–253.

Unfortunately, the first experiments were discouraging. The micelles required gamma irradiation to polymerize, and the common anticancer compounds we tried were chemically degraded by gamma radiation, so they could not be encapsulated. We decided to proceed by encapsulating fluorescein as at least a test of the nanocapsule’s ability to enter cells. Fluorescein makes cells fluoresce, but cannot diffuse by itself into cells as a free compound. When we incubated the loaded nanoparticles with rat fibroblasts, the cells became strongly fluorescent—and they were unaffected when we incubated the cells with the free fluorescein molecules. Thus we had our first proof of concept that polymer nanoparticles could induce cells to capture a nondiffusible compound.

But there were more problems to overcome. The polymer used in this work was not biodegradable, and the materials used to create it were potentially toxic. We found the answer to our search in a surgical glue based on cyanoacrylate. In another serendipitous connection, a process was found that allowed these monomers to polymerize in water, without the use of any radiation, into nanoparticles about 50 to 300 nanometers in diameter. The resulting polymer, called polyalkylcyanoacrylate or PACA, was biodegradable and made with a nontoxic process, so it did not damage the anticancer compounds we wanted to encapsulate.

One compound given special attention for loading into PACA nanoparticles was doxorubicin, which has a broad spectrum of anticancer activity but also causes cardiotoxicity. When encapsulated in nanoparticles that targeted specific tissues, heart exposure to the compound could be limited. Studies showed that after the loaded particles were delivered intravenously, they were preferentially captured by the liver, whereas the drug concentration in the heart was dramatically decreased. As a result, we considered this nanomedicine as a potential treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma, a severe disease with poor prognosis in large part because of its hyper-expression of efflux proteins, which allows the cancer cells to pump out anticancer therapies. It was hypothesized that when encapsulated into nanoparticles, doxorubicin could be masked from recognition by these membrane transporters.

Indeed, we found in cell studies, when compared to the free drug, doxorubicin-loaded nanoparticles were more toxic to multidrug-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. In animal studies, my colleagues and I found that after intravenous administration, the loaded nanoparticles accumulated in liver Kupffer cells, phagocytic cells that break down both bacteria and worn-out red blood cells. These Kupffer cells then became a reservoir for the doxorubicin, creating a gradient of drug concentration that resulted in a massive and prolonged diffusion of free drug toward the cancer tissue. These loaded particles, and not the free drug alone, induced impressive cell apoptosis that was restricted specifically to the hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

These data supported initiation of clinical trials in humans. The Phase III trial took place from 2015 to 2019, but the resulting data showed the survival between the groups was equivalent to the standard of care for hepatocellular carcinoma, which improved over the extended period of time of this trial. As a result, the nanoparticles came too late and missed their opportunity to become best in class for this indication.

Our mixed experience with PACA nanoparticles in clinical trials led to the next serendipitous research story. My doctoral student at the time, Barbara Stella of the University of Turino in Italy, and I wanted to test the particles with a different compound, gemcitabine, which has broad anticancer activity but a short biological half-life because it is rapidly metabolized. Gemcitabine is unfortunately hydrophilic, so it would not load efficiently into the nanoparticles. This was a very disappointing result.

Adapted from Science Advances 6:eaaz5466.

Rather than give up and change the drug to be encapsulated, the idea came to us to use a derivative of gemcitabine that is lipophilic. Despite our synthetic efforts, these prodrugs were not soluble in water and therefore not amenable to the PACA nanoparticle preparation process, which takes place in a water medium. These discouraging results then gave us the idea to use a lipid with a more condensed molecular formation. It is not advisable to inject a cholesterol derivative, so we focused our attention on squalene, a biocompatible lipid precursor in cholesterol biosynthesis. Remarkably, this compound is widely distributed in nature and adopts a dynamically folded molecular conformation in water. So we chemically attached squalene to gemcitabine and prepared a batch of PACA nanoparticles with gemcitabine-squalene as the prodrug to be encapsulated. To test the resulting mixture, we centrifuged it, but we found unexpectedly that all of the gemcitabine-squalene turned up as sediment particles—and the same happened if we centrifuged the prodrug without the nanoparticles. We discovered that the chemical linkage of gemcitabine to squalene resulted in molecules that were capable of assembling spontaneously in water into nanoparticles of 100 to 300 nanometers in diameter—no polymer particles needed for encapsulation.

In addition, we were able to calculate that the drug loading into these nanoassemblies was 41 percent by weight, whereas the best reported result with other nanocarriers was 8.3 percent by weight. By moving from the “physical” encapsulation to the “chemical” encapsulation paradigm, this so-called squalenoylation technology moved the nanotechnology field a step forward. It resolved the low drug loading issue and avoided the “burst release” of drugs that is often associated with nanocarriers.

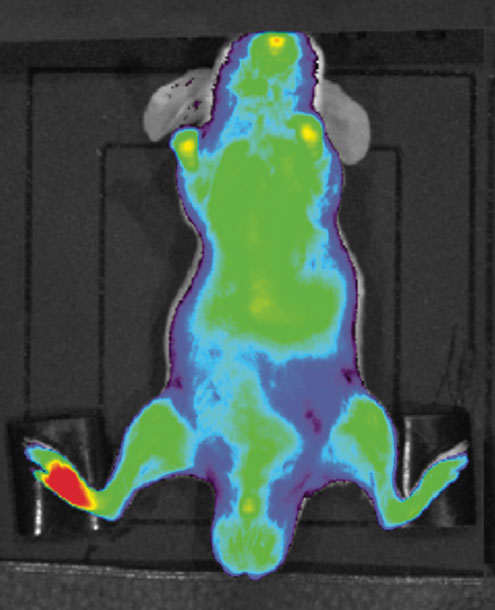

The squalenoylation process has demonstrated high versatility that does not apply only to small cancer drugs. We have also explored its applicability to the treatment of neurological diseases such as stroke or spinal cord injury, considering the possibility of designing nanomedicines capable of acting on peripheral rather than central receptor targets. Recently we have focused on the development of endorphin neuropeptides for alleviation of pain, where squalene nanoparticles specifically target inflammatory tissues (see figure above). Multidrug nanoparticles may also have the potential to treat uncontrolled inflammation associated with many diseases, including severe medical issues that result from COVID-19.

Nanocarriers show great promise for the protection, targeting, and delivery of treatments in ongoing clinical trials. There are still complex barriers to overcome to bridge the gap between the research bench and the patient bed, but I am optimistic that innovation—and a dose of serendipity—will keep pushing nanomedicine to the next state of the art.

This article is adapted from Journal of Controlled Release 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.04.028.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.