Beautiful Armor

By Andreia Salvador

The rich variety of mollusk shells reflects the diversity of the phylum, which has fascinated humans for millennia.

The rich variety of mollusk shells reflects the diversity of the phylum, which has fascinated humans for millennia.

The beautiful shells pictured here belong to one of the most diverse groups of animals on the planet: mollusks. These invertebrates include snails, oysters, cuttlefish, and chitons, each with their own characteristic type of shell. Most snails have a spirally coiled shell, oysters have a pair of shells called valves, cuttlefish have an internal shell, and chitons have an armor-like shell made up of eight separate pieces. And some mollusks, such as slugs, do not have a shell at all.

For those mollusks that have one, their external shell provides protection for the soft body. The shell is made of calcium carbonate and a tough protein called conchiolin, which forms the shell matrix into which the calcium carbonate is deposited. Both components are secreted by the mantle, a thin layer of tissue that covers the soft parts of the mollusk’s body. As the animal grows, more shell is secreted by the mantle, enlarging the shell.

All of the shells featured here come from collections held by the Natural History Museum, London. The size given for each shell refers to its largest dimension (including any spines or other ornaments). The accompanying geographic distribution information gives the known range of the species.

In many parts of the world, until the end of the Roman Empire circa 500 CE, this little shell was used as currency. It continued to be used as small change in the markets of Benin, Ghana, Ivory Coast, and Burkina Faso into the 20th century. Many factors contributed to the shells’ success as money, but probably the most significant were that they could not easily be counterfeited (though imitations were produced from bones, ivory, stones, and bronze), they were a convenient and constant size, and they were durable and could be transported easily, like coins. In 18th-century Uganda, one could purchase a cow for 2,500 of these shells, a goat for 500, and a chicken for 25.

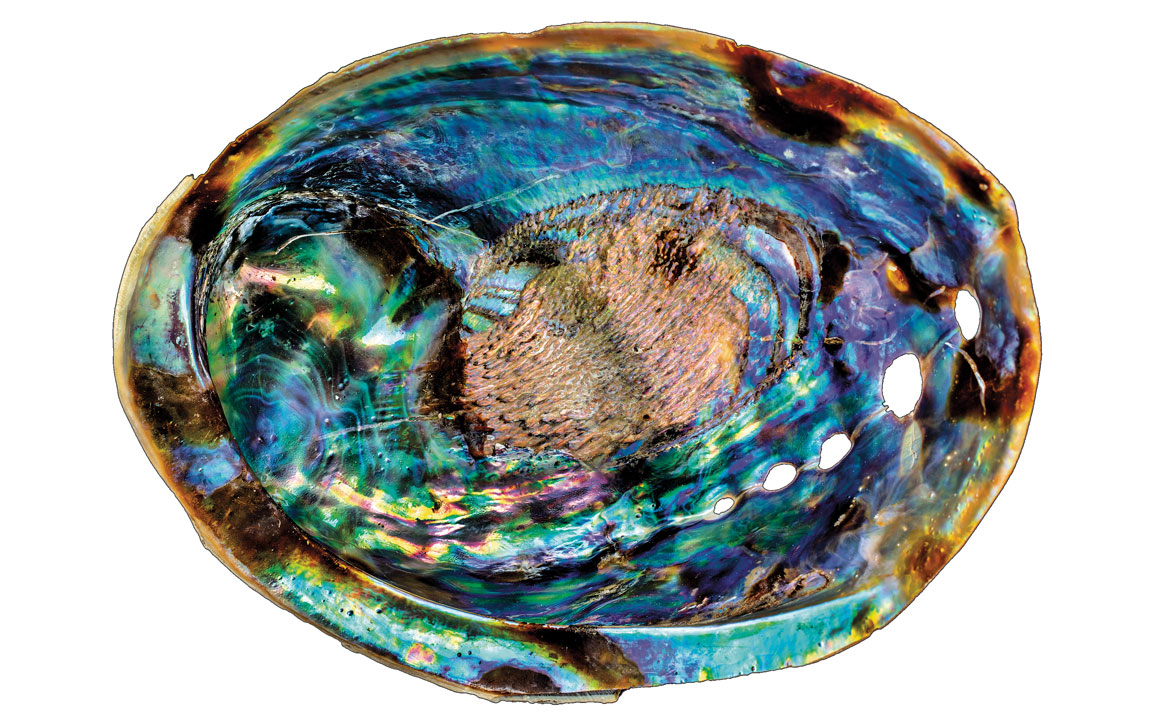

The shell of a mollusk is made almost entirely of calcium carbonate, which the animal extracts from food and seawater. The three layers of the shell are formed simultaneously by the mantle. The outer layer, or periostracum, is usually brown or black in color, or is absent in some groups. The second layer, or ostracum, is formed of calcite crystals, and the third layer, or hypostracum, is formed from aragonite (both calcite and aragonite being different forms of calcium carbonate). In some mollusks, the aragonite crystals cement together in overlapping layers to form mother-of-pearl, or nacre. The iridescent colors of nacre are not produced by pigments in the shell but instead are derived from the physical properties of the crystals. Shells that have nacre are polished and carved to make jewelry, buttons, or decorative objects. The pāua, a species of abalone that is only found in New Zealand, is renowned for its blue and green iridescent mother-of-pearl.

For thousands of years, people have known how to extract dye from mollusks. The Phoenicians of Tyre in southern Lebanon perfected the process for making a dark reddish-purple dye known as Tyrian purple. This long-lasting dye was taken from several species of whelks, including the purple dye murex, Bolinus brandaris, and the banded dye murex, Hexaplex trunculus, which are found on the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts. When a murex is disturbed, it retreats into its shell and ejects a fluid, which initially is colorless but, once exposed to sunlight, gradually turns from yellow to green to blue and finally to a purplish red. The dye was expensive—for one gram of dye, more than 10,000 snails were needed. For this reason, the dye was reserved for the garments of individuals of the highest rank. Today, synthetic versions of such pigments are manufactured.

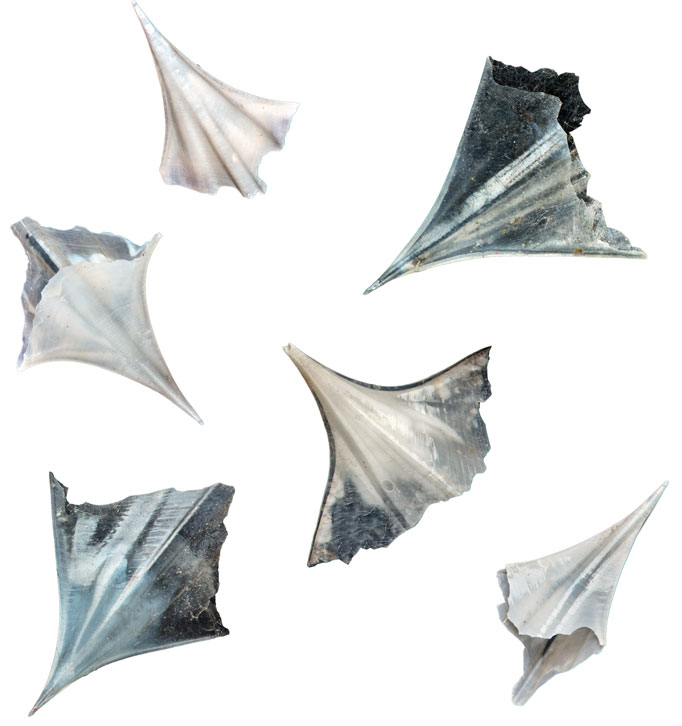

The windowpane oyster is one of the most flattened bivalve mollusks. Its greatly compressed valves hardly leave room for the animal, which lies on the right valve. This oyster is abundant on the muddy bottoms of quiet lagoons, bays, and mangroves in the tropical Indo-West Pacific. It feeds mostly on plankton and organic detritus. Its shell is thin, brittle, and translucent, with a pearlescent appearance, and its outline is nearly circular. This species’ common name is derived from its long-standing use in windowpanes in place of glass in various Asian countries. The shells can still be found in the windows of old homes in the Philippines, where they are fished in large numbers and are also manufactured into screens, lampshades, and ornaments.

The direction in which a mollusk shell’s whorls are coiled is an important characteristic. The majority of shells are coiled clockwise (dextral), but a few species coil counterclockwise (sinistral). However, amphidromus tree snails are unusual; they are chirally dimorphic, meaning that in the same population one can find both dextral and sinistral individuals. One reason for this variation could be related to their natural predators, snakes. Most snail-eating snakes of the genus Pareas have elongated teeth on the right mandible, and for that reason specialize in predation on the dextral shells. These snails have evolved by coiling the other way, which makes it difficult for the snake to grasp and eat them.

Coral reefs are one of the richest and most diverse environments on Earth, providing complex and varied marine habitats that support a wide range of organisms. They cover less than 1 percent of the global marine ecosystem, yet they provide a home for 25 percent of all marine species, including thousands of mollusk species. But coral reefs are under threat worldwide. In addition to anthropogenic challenges, one major concern is the crown-of-thorns starfish. These starfish can grow as large as 1 meter in diameter, and they feed on coral. The horned helmet is one of the few species of mollusk that predate on the crown-of-thorns starfish. For this reason, the horned helmet has been put under strict protection in Queensland, Australia, in a bid to prevent the starfish spreading and consuming the Great Barrier Reef.

Most gastropods have regular, neatly coiled shells, but the West Indian worm shell is an exception. Its shell is thin, twisted, and tubelike. The first whorls curl regularly, but as the animal grows, the later whorls become progressively more uncoiled and distorted, so that no two specimens are identical. These marine snails are sequential hermaphrodites—they start their adult lives as free-living males, but later change sex and become sessile females, attaching themselves to various substrates such as sponges or other colonial animals.

These colorful freshwater snail shells are a wonderful example of the diversity in molluscan shell color, and, although the pattern on each is different, they are all representatives of the same species. Such variable appearance within a species is known as polymorphism. The advantage of looking different is possibly very easy to explain: If they all looked the same, predators would only have one pattern to recognize when hunting. With many different patterns, the zigzag nerite confuses predators by making it difficult to establish a consistent search image of their prey.

Many marine mollusks burrow into the sand or mud of the seabed to hide from predators. Others, like all members of this family of bivalves, the piddocks, are borers. They excavate permanent tunnels in mud, clay, limestone, wood, or even rock. They bore by a slow twisting movement of the valves, controlled by their muscular foot. The thin and usually elongate shell has a very rough surface on the front end that rasps into the substrate. Angelwing clams have strikingly beautifully white shells. They live in shallow, subtidal waters, boring in soft mud to depths of up to 1 meter. They are suspension feeders, feeding solely on plankton, and are usually found in scattered colonies of several dozen individuals.

This small, fragile, and translucent shell belongs to a group of pelagic gastropods called pteropods. The world’s oceans are heavily populated with these small snails, which form part of the plankton. Pyramid clio provide a vital source of food for many small and large aquatic organisms. They are also named sea butterflies because the animal has two large, winglike extensions on its foot, which can be flapped like the wings of a butterfly. Because their shells are exceptionally vulnerable to rising levels of carbon dioxide, these organisms have been proposed as bioindicators to monitor the effects of ocean acidification. Acidification occurs when oceanic waters absorb the atmospheric carbon dioxide released mainly from the burning of fossil fuels. At a certain threshold, the acidity dissolves the snails’ shells, and they, like many other mollusk species, cannot survive without their shell to protect them.

Nautiloids are the only group of living cephalopods with true external shells. The nautilus has a shell made up of chambers, which are connected by a tube called the siphuncle. The animal occupies only the last chamber of the shell, into which it can withdraw completely. As it grows, it creates a new larger chamber, using its 90 or so tentacles to move its body into the new space and sealing off the vacated one. Nautilus shells had been carved, etched, and engraved for many centuries. They rose to prominence in Europe during the 17th century when European craftsmanship reached new heights, particularly in the Netherlands. The carved shells were popular items in cabinets of curiosities and were among the most coveted natural history objects.

Moon snails, or necklace shells, belong to a large family comprising several hundred species distributed throughout the world. They are an extremely diverse group that spans all marine habitats, from pole to pole, from the intertidal to the abyssal depths. These gastropods are active predators, feeding mostly on bivalves that live below the surface of the sand. After enveloping their prey with their disproportionately large foot, the snails drill a very neat circular hole through their victim’s shell in order to eat the animal inside. They use their radula to drill the hole and scrape away shell material, which is softened by a chemical secreted by an accessory organ. This method does not work every time, so the shells of prey species may be found with unsuccessful drill holes.

Photos and text are excerpted and adapted from Fascinating Shells: An Introduction to 121 of the World’s Most Wonderful Mollusks by Andreia Salvador, published by Natural History Museum, London, and the University of Chicago Press. © 2022 by The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.