This Article From Issue

November-December 2023

Volume 111, Number 6

Page 376

ON THE ORIGIN OF TIME: Stephen Hawking’s Final Theory. Thomas Hertog. 352 pp. Bantam, 2023. $28.99.

Last year, I had the opportunity to give a TED Talk on the main stage. A few days before the event, I had dinner with other people who would also be giving talks about science. As we settled in, a nuclear energy influencer (that’s a thing, I learned) asked me what I did. I explained that I’m a theoretical particle cosmologist, who mostly tries to understand what dark matter is. She looked at me with sincere confusion and asked, “How is that useful?” With On the Origin of Time: Stephen Hawking’s Final Theory, Belgian physicist Thomas Hertog offers a passionate rebuttal to those who think the only science that matters is that which has obvious and near-term material value.

Photo credit: Thomas Hertog and Jonathan Woods.

The answer to that influencer’s question? As Hertog writes, “Stephen’s final theory offers a powerful kernel of hope.” Braiding together the history of cosmology and the story of his working partnership with Hawking, Hertog contributes to the extensive literature for general audiences on the origins of the universe by offering, at heart, an homage to a beloved mentor. Hertog completed his doctoral work under the supervision of Hawking, which is explored in On the Origin of Time, and this led to an enduring research partnership that was still productive until nearly the end of Hawking’s life.

The “final theory” mentioned in the book’s title addresses the questions that Hawking spent his entire career chasing: How did space-time begin, and what is a correct narrative of its evolution? Ultimately Hawking, in collaboration with Hertog and other scientists, came to the conclusion that in order to understand the past, we must begin with the present and understand that quantum mechanics means there is no such thing as a classical, linear past unfolding behind us. This top-down approach, as Hertog terms it, is antithetical to our typically taught and learned understanding about time.

But for physicists, especially cosmologists, this perspective is nothing new. Our early training as relativists involves reconfiguring our conception of time as both relative and, under many circumstances of interest, mixing with space, to form space-time. Our training in quantum theory also teaches us that even the simplest physical systems do not necessarily have a deterministic evolution like the one that Newtonian physics promises us. In other words, we can calculate probabilities about the final state of a system, but we cannot guarantee it. What happens when you apply this idea to the whole universe at once? Hertog claims that, necessarily, one must land at a theory of quantum cosmology that he calls Hawking’s final theory. This means that we must let go of fixed notions of history where there is only one pathway to the past. In other words, we must shift away from deterministic notions of physical history.

In trying to summarize the top-down model for this review, I faced a challenge that Hertog also had to confront head-on in his more than 300-page text. A decent amount of background material is necessary in order to fully appreciate the ideas from which Hertog and Hawking drew to develop their no-boundary model of how the universe began. For example, readers must understand that if we run our cosmological models—as described by Einstein’s gravitational equation—in reverse, we land at a mathematical singularity at time equal to zero. The jury is still out on whether this is a physical singularity—a phenomenon where space-time is no longer well-defined. At base, this is the problem that Hawking (who was also responsible for identifying it) spent the rest of his career investigating.

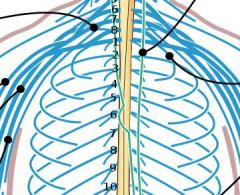

We are not hopeless in this pursuit: The space-time singularities that arise in what we term classical cosmology potentially go away, or at least shift in nature, when we bring quantum mechanics into the picture. Hertog chooses to narrate these scientific questions largely through the frame of history, first by giving a chronological narrative of classical cosmology, then offering an introduction to how quantum gravity string theory provides fresh insights, before finally returning to the fundamental ways in which basic ideas and results from quantum mechanics encourage us to rethink absolutely everything.

Before arriving at these historically infused (and almost exclusively men-only) introductions to the quantum and cosmological questions at hand, Hertog offers an extensive chapter on how Darwinian evolutionary theory reconfigured biology, providing insights from which Hertog and Hawking would later borrow. In my view, that promise is unfulfilled before the book is over, but it wasn’t overly bothersome to me. The question of how to interpret the history of our cosmos without the guarantee of determinism is a fundamentally profound question that will bother physicists in the best possible way, but will also be interesting and exciting to any curious person who has the right conditions to sit and wonder.

Due to the way the book is set up and the order in which Hertog presents events and ideas, we don’t get to the cool ideas soon enough. The early excursion into evolution and biology could have been cut short, if not entirely. When I’ve asked colleagues about the ideas that Hertog advances at the very end of the book, some of them feel that the final theory is more vibes than substance, but I’m alright with that. I wish I had spent more of the book knowing what vibes we were going to land in, with a stronger sense of where Hertog was leading the reader. In addition, Hawking’s genius and reputation are so imposing on the text that Hertog himself disappears, to a certain extent. I find that unfortunate, because he is an accomplished scientist in his own right who has coauthored nearly 100 scientific papers—mostly with people who are not Stephen Hawking—on a range of topics that tackle major questions in theoretical cosmology.

Overall the book is hagiographic in nature, but I struggle to impugn this. I also have scientific mentors, at least one of whom is mentioned in this book, about whom I would write only the most glowing words. While I could have done without Hertog’s historical approach to narrating scientific ideas, On the Origin of Time works hard to capture some of the awe-inspiring spirit of Hawking’s A Brief History of Time, complete with extensive explanations and helpful figures. At the age of 10, I chose theoretical cosmology because I saw a documentary based on that bestseller; this book might do the same for someone else.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.