This Article From Issue

March-April 2022

Volume 110, Number 2

Page 118

THE DAWN OF EVERYTHING: A New History of Humanity. David Graeber and David Wengrow. xii + 692 pp. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2021. $35.

The history of the entire world is a tempting topic, one that many modern authors have been unable to resist. Taking it on means writing a very long book (or many books), or writing a book with a strong theme or theory in mind. The sweeping world histories thus produced have often disgruntled or frustrated the people who know most about human history—that is to say, historians and anthropologists, who have been particularly irritated in recent years by the world histories of authors such as Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker, and Yuval Noah Harari. David Graeber and David Wengrow’s ambitious “new history of humanity,” The Dawn of Everything, will provide frequent pleasant relief for the unhappy readers of these other authors, not least because the book expressly criticizes other world histories. However, Graeber and Wengrow have more in mind than simply complaining of Pinker’s misuse of evidence or Diamond’s reductionist explanation of modern global inequality.

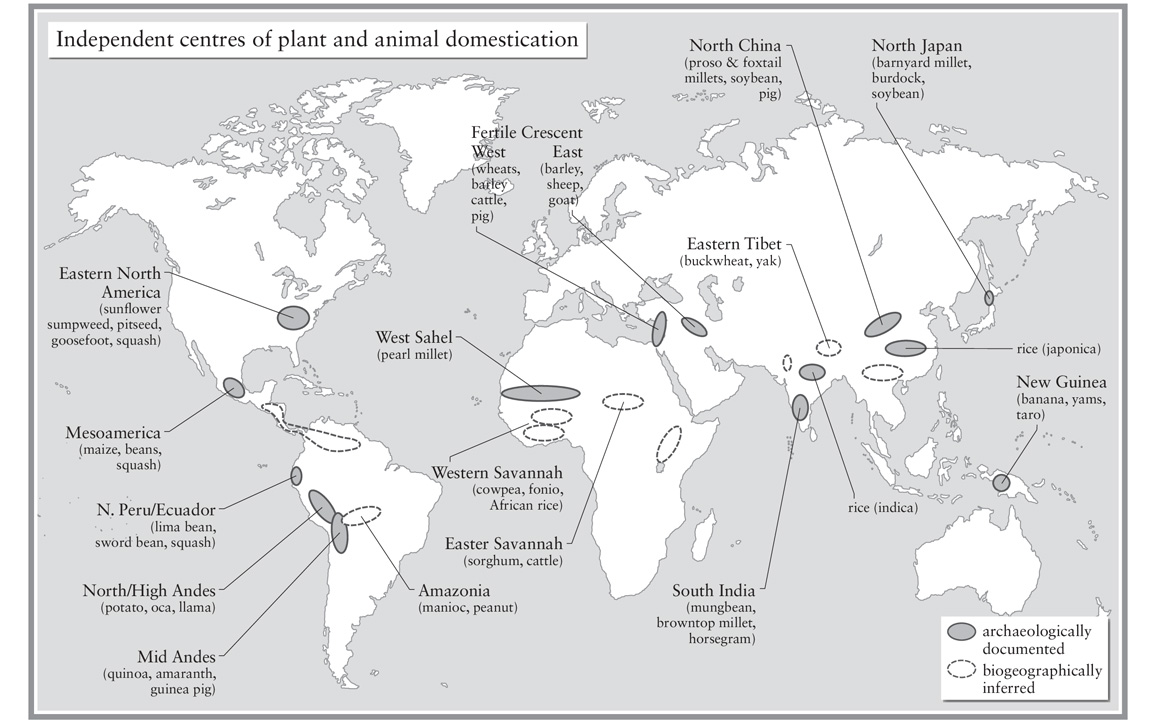

The illustration above, "Independent centres of plant and animal domestication," was adapted from an original map, courtesy of Dorian Q. Fuller. From The Dawn of Everything.

They contend that human history at the biggest and longest scales is not a linear process that moves inexorably toward an inevitable present. Nor is it reducible to a set of laws or reliably determinative regularities. Human history, they argue, is composed of a great many small and mutable histories; it is the product of many choices that have gone in a variety of directions. They do not seek to replace simple monocausal narratives with a simple narrative of their own, save to say that all such simple narratives are empirically wrong and stem from troubled ideological roots.

This vision leads to some structural and conceptual problems with the book, as I will later explain. But I want to start by noting the tremendous virtues of this ambitious and frequently compelling work. It is the only book of its genre—“big-picture, done-in-one, from-A-to-Z” world history—that makes its case in a way that is consistent with the vast body of scholarship by historians and anthropologists compiled over the past century. Most potently, The Dawn of Everything respects the fact that the work of historians and anthropologists reveals immense variation and dynamism in human societies over time, in contrast to reductionist and teleological world histories that have regarded that immense range only as data to be cherry-picked. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, Pinker takes the male violence of the Amazonian Yanomami to be evidence of what all human beings were like before the arrival of agriculture and the formation of states, ignoring innumerable other foraging groups. In “The Original Affluent Society,” Marshall Sahlins uses two African foraging societies, the Hadza and the !Kung, to argue that “Stone Age economics” produced idyllic and bountiful lives full of time for leisure and sociality, even though numerous counterexamples exist. Much of The Dawn of Everything scrutinizes well-known or influential work of this sort, all the way back to the 18th century, invariably finding it wanting.

As Gideon Lewis-Kraus notes in his review of The Dawn of Everything in the New Yorker, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz once worried about “spiteful ethnography,” in which narrow specialists stubbornly insist that a single contradictory example destroys a big-scale theory. But Graeber and Wengrow observe that time and time again the issue is not a single contradiction poking a very small hole in an otherwise intact theory; rather, the problem is that many existing generalizations about human history at the grand scale rest on very limited and highly selected evidence or just on assumptions, especially when what is being discussed is the era between 200,000 years ago and 20,000 years ago. The authors point out that when we do know a good deal, that knowledge contradicts many common generalizations, and when we know very little, there are grounds to consider many other assumptions than the ones we have come to accept.

For example, when they write about the attempts of other authors to manage the definition of “true foragers” in order to dispose of numerous inconvenient contradicting or divergent examples, Graeber and Wengrow insistently bring into play the general variety of ways that foragers actually have lived over time. They build upon a wide range of revisionary studies of the history of agriculture to emphasize that agriculture was the emergent outcome of long cycles of relatively sedentary foraging. They note that agriculture was highly variable in different locations, and that it did not lead to an irreversible dependence upon farming and hence to urbanization and centralization.

Graeber and Wengrow also shuffle through the deck of other bodies of social conjecture that are frequently taken to be obviously true: that cities and elaborate administrative hierarchies appeared simultaneously and were inextricable; that agriculture inevitably produced cities; that the only egalitarian societies have been very small in scale and were based on kinship relations; that particular environments or ecologies were predestined to produce certain kinds of scales and structures in human societies. They find all of these conjectures wanting.

They do so, chapter by chapter, by repeatedly challenging both the way that older scholarship used archaeological and archival evidence and the way it used inference to come to its conclusions. Among other points, they note that many of the common theories and narratives in universal history rely almost exclusively on examples and evidence from Western Europe and the Near East. This bias is not merely a result of intellectual Eurocentrism or the dominance of European and American academic institutions in the production of knowledge. Large portions of the world that have been inhabited for millennia have received very little dedicated attention from archaeologists due to a lack of funding and to difficult conditions at possible field sites. In addition, most of the evidence for the aforementioned conjectures comes from societies that built with materials that survive for centuries or millennia, such as stone, metal, and ceramics. However, there were probably many human societies in the distant past for which evidence is absent despite their having built and made things at large and small scales, because they worked with materials that don’t last as long, such as wood, mud, earthworks, and leather.

The authors dig with gusto into cases that have been defined as exceptions to the rule; they do so in order to make the case that the rules are the real problem.

Graeber and Wengrow also note the frequency with which experts in particular fields step around the cases that don’t fit their simpler generalizations. Some of those cases are very well documented, such as the city of Teotihuacán. As they note, experts agree that Teotihuacán was remarkably large and complex at a very early date in the history of the Valley of Mexico, but those experts otherwise bracket off Teotihuacán, describing it as a “weird” place that exhibits a “stubborn refusal to conform to expectations of how an early Mesoamerican city should have functioned.” Graeber and Wengrow argue instead that there is considerable reason to think that Teotihuacán was governed “without overlords” or elaborate hierarchy, a state of affairs they say was not unusual in the history of this region or many others elsewhere in the world. By this point in the book, readers know what’s coming next, because Graeber and Wengrow repeatedly dig with gusto into cases that have been defined as exceptions to the rule; they do so in order to make their case that the rules are the real problem.

The Dawn of Everything argues for the general importance of human agency throughout human history. For me at least, this is the book’s most challenging, interesting, and generative claim: that the variation and difference that historians and anthropologists document in their scholarship is at least partially the product of human societies deliberately shaping themselves in dynamic relation to other human societies, often as a commentary upon their neighbors. Graeber and Wengrow acknowledge that environment and technology matter, and that they constrain the kinds of choices available. But they do not believe that environment and technology are determinative in and of themselves.

This is a satisfying reframing of a great deal of human history. For example, if I think about the societies of West Africa around 1500, at the start of new connections to trade and contact at the Atlantic coastline, I’m struck right away by the variety of social and political arrangements just along the arc from the Senegal River to the Upper Niger and hence down to the Niger Delta. There are small centralized states sharing common cultures; there are loose fluctuating empires; there are tightly organized imperial states with highly elaborated political institutions; there are cosmopolitan cities, full of merchants and scholars, that are at least partially self-governing; there are densely inhabited towns with shared commercial and social institutions and a democratic ethos that spurns centralized rulers; there are isolated groups of foragers; there are fishing and foraging people who live right next to centralized states and interact frequently with them; there are pastoralists with elaborate institutions of their own who are moving continuously if slowly eastward; and there are pastoralists who inhabit the trans-Saharan world who periodically attack but also service the cities and farming communities along the Upper and Middle Niger.

These variations are not the inevitable product of different environmental preconditions within West Africa, nor are they analogous to drivers who are at different positions on the same road but are headed for the same destination. Graeber and Wengrow’s vision of world history would have us instead see these variations as a shifting conversation or argument between human beings across such a region. If Igbo communities in the Lower Niger steadfastly rejected centralized authority while building elaborate commercial and cultural institutions that linked them together, then perhaps that was because they saw their neighbors’ elaborately centralized and military state—the Oyo Empire—and they didn’t care for it. (And vice versa.) It’s a vision of world history that scales down to individuals and casts a new light on what historians frequently see in the historical record, which is people as individuals and small groups making choices, driven by affinity and aversion to join or emulate a new society, or to flee or reject their old one.

Graeber and Wengrow freely concede that their reframing of world history is tied to an anarchist political project. I have no quarrel with this vision as such, but it does put some strains on the book. These strains are most visible in the book’s repeated focus on equality and egalitarianism. The authors are at great pains to argue that when human societies have been devoted in some respect to egalitarian social arrangements, that devotion has not been a by-product of size, scale, or environmental circumstance. This proposition puts them at odds with intellectuals and scholars (including other anarchists) who argue that the evidence for an association between small-scale foraging societies and egalitarian norms is robust.

Perhaps as a consequence, Graeber and Wengrow are mostly uninterested in human societies that have been hierarchical, unequal, centralized, or aggressive. They’re interested in dethroning those societies from their privileged status as typical or inevitable. But such societies are not rare. If we are to understand human beings as active agents in shaping societies, then applying that concept to societies at any scale that have structures and practices of domination, hierarchy, and aggression should be as important as noting that these societies are neither typical nor inevitable.

Graeber and Wengrow eventually do get around to this problem in chapter 10, “Why the State Has No Origin.” They stick to the point that such states and empires should be understood as the exception to the way that most human beings have chosen to live. However, centralized and hierarchical states often have taken those choices away—in some cases by conquering their neighbors. More complicatedly, some human beings—and not merely those at the top of the social hierarchy—may have had a preference for or investment in these approaches to human existence. Insofar as the authors do have an argument about the development of societies that were unequal, violent, or hierarchical, it’s a seeming reprise of the book’s overall vision. “State formation” can mean many things, they say—“It can mean a game of honour or chance gone terribly wrong, or the incorrigible growth of a particular ritual for feeding the dead; it can mean industrial slaughter, the appropriation by men of female knowledge.” However, many of the things it can mean are accidents rather than choices, processes that got out of control. And there are moments in this line of argument when the reader glimpses an anarchist’s assumption that people would never of their own volition choose dominance and hierarchy, that it would have to be imposed on them.

To some extent, the book’s emphasis on mutability and variety over time also means that Graeber and Wengrow deemphasize the cumulative weight of historical precedent and change on each successive century of human existence. It’s important to kick ironworking, agriculture, the state, and the like off their teleological thrones—to stop assuming that they are inevitable or irreversible, and to pay attention to the degree to which human societies undo, redo, rethink, abandon, or sift through technologies, processes, and institutions. However, over time, new technologies, new social formations, and institutional structures in history do begin to press in on the range of choices available to people later on. Cities don’t have a single inevitable form or a single reason for being, but once cities start to appear, it’s plain that they’re never going to be entirely unthought of or unchosen, which will lead to more cities over time—ones that are to some extent based upon or shaped by previous cities. Path dependence is real. The accumulation of ways of making and living gains a kind of inertial force that Graeber and Wengrow acknowledge but do not really emphasize or explore. The fact that societies really do draw on the technologies and ideas that came before undercuts the authors’ notion that each historical event is its own unmoored instance of human agency at work.

Their abiding interest in dethroning inequality, empire, agriculture, and urbanization as the inevitable linear outcomes of human experience also perversely means that The Dawn of Everything shares the defect of some of the global-scale histories that it most sets itself against. Jared Diamond essentially concludes that the past 500 years since the rise of the West are the inevitable epilogue of the initial geographic distribution of early human populations; he gives that time span no independent causal importance in shaping contemporary global inequality. Even though Graeber and Wengrow disagree with Diamond’s approach to history, like him they don’t have much to say about the modern world—except to say that it is not the product of all the millennia that came before, and to acknowledge that the conditions that made variation possible in the human past are no longer in force today. They end up in the camp of those who see modernity as the product of a dramatic rupture or break in human experience, but their approach makes it difficult to say why or how that might have happened.

The Dawn of Everything is a huge resetting of almost two centuries of assumptions and unsupported axioms.

Wrestling with modernity—or at least with its impact on most historical thinking—also may have inspired the most troubled chapter in the book, “Wicked Liberty,” which is unfortunately the second chapter. “Wicked Liberty” takes a long and pugnacious detour into dethroning Thomas Hobbes and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Because Hobbes understood human prehistory to be brutishly violent, he understood historical time to be primarily about the ascension of a state capable of maintaining order; likewise, because Rousseau understood human prehistory to be peacefully egalitarian, he understood historical time to be primarily about the ascension of a society devoted to inequality.

Graeber and Wengrow seem to have intended the chapter as a kind of cleansing exorcism meant to open up the rest of the book’s analysis, but in my view, the chapter is unnecessary. The authors criticize intellectual history’s reliance on singular texts while curiously reproducing it by claiming too much influence for the writings of Hobbes and Rousseau, thereby compressing the vast complexity of how we came to have the ideas we have today about inequality, “the state of nature,” and history.

In this chapter Graeber and Wengrow also set out to argue that Rousseau was rebranding an Indigenous Native American critique of early modern European societies. On this point, the authors are stepping inexpertly into a sprawling argument within anthropology, history, and critical theory about the proper interpretation of early modern texts describing, witnessing, or speaking for non-Westerners, and they appear not to recognize the extent to which this argument has been going on among scholars for decades. The possibility that Native Americans in eastern North America might have been shifting their own practices in order to craft an embodied, practiced critique of what they disliked about the communities of European settlers is an important demonstration of points made later in the book. However, the historiography of interpreting textual evidence for such shifts deserves more patient attention and should have been brought up at a later point in the book, if at all. In many ways, the book would be stronger if it simply moved from the first chapter to the third, “Unfreezing the Ice Age,” which best exemplifies the authors’ overall argument.

In any event, it would be a shame for discussions of the book to get hung up on chapter 2. For anyone seeking to defend the narratives that Graeber and Wengrow set out to challenge, there is work to be done, and not merely at the level of a directly argumentative response to this book. Also, critics of the book might find that their time would be best spent reexamining in a detailed way the evidentiary foundations of their own assumptions about the past.

The Dawn of Everything is a huge resetting of almost two centuries of assumptions and unsupported axioms; in Kuhnian terms, it demolishes a paradigm. I am not always sure that Graeber and Wengrow are right in their own readings of history, but I am sure they’re right that many people have been wrong, whether because of conscious cherry-picking or because of the inertial force of prior social theories. (Agriculture is a great example of this inertia. Research about the early origins of agriculture makes clear that it was a long process that arose as a complex system out of foraging and seasonal migration, yet somehow that research hasn’t led to wide recognition that some societies started doing more systematic cultivation and then abandoned it when it required too much labor, other societies undertook cultivation only in limited ways, and still others started enslaving people and forcing them to cultivate, only to abandon agriculture when uprisings took place.)

My hope is that this book will serve as a huge eraser, inviting everybody to think in fresh ways about what we think we know, and to question everything.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.