Alzheimer's Disease

By Vernon Ingram

The molecular origins of the disease are coming to light, suggesting several novel therapies

The molecular origins of the disease are coming to light, suggesting several novel therapies

DOI: 10.1511/2003.26.312

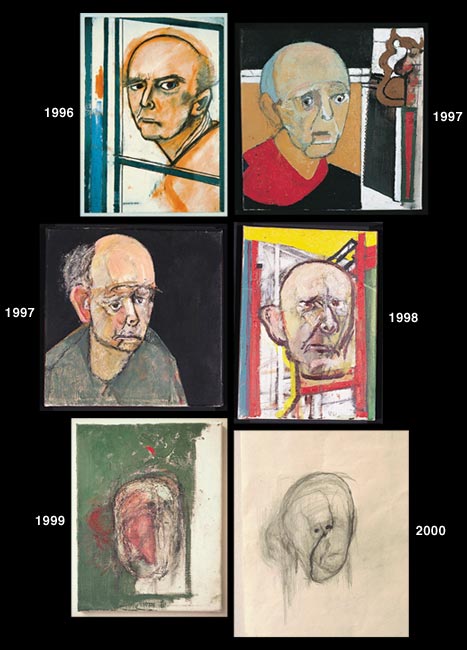

The essential nature of Alzheimer's disease—losing your mind—terrifies everyone who has seen a friend or family member fall to its advance. Alzheimer's disease is devastating, and, despite great strides in recent years, still puzzling in its cause and mechanisms.

Some cases, fortunately few, clearly run in families and strike early; the rest begin later, but show an equally relentless decay of personality. For the minority carrying early-onset Alzheimer's mutations, the genetics are cruel and implacable: If you have inherited one of those genes, you will develop the disease. Yet the great majority of cases do not demonstrate such a clear inheritance pattern. Of this majority, some represent inherited genes that give a higher-than-average chance of developing the disease. Other cases arise in the absence of known genetic risk factors and show no hereditary pattern. What turns these genetic chances into reality? More important, what can we do to stave off the disease once a diagnosis is made?

Galerie Beckel Odille Boicos, Paris

The answer to the first question is disappointing. Science doesn't know yet. What is known is that age is the most important risk factor. Even the familial form of the disease does not usually begin until the mid-50s, and the nonfamilial (more common) form starts much later, in the 70s or 80s. However, in both cases the brain pathology and cognitive deficits are the same, pointing to a common molecular mechanism.

The answer to the second question—how to treat the disease—is close but also out of reach. There are very few approved treatments for the psychological symptoms (memory loss, disorientation, personality changes), and the few that have been described seem to afford only very partial and short-term relief. Therapeutic options do exist for relieving secondary symptoms, including depression, anxiety, restlessness, hallucinations and sleep disorders. However, a cure or treatment for the underlying cause of Alzheimer's remains elusive.

Mercifully, the gloom of this dark preface is lifting. Many research groups around the world are seeking to understand the disease at a fundamental level. Already, many insights into Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis have emerged, several promising drug therapies are on the horizon, and a few candidates are entering clinical trials. These compounds pursue diverse strategies, but all aim to halt or even reverse the molecular events that are precursors to cell dysfunction and cell death. In our laboratory, my colleagues and I have developed a model that explains the neurodegenerative mechanism of Alzheimer's disease, and we have some promising data on a novel method of blocking this pathogenic process.

PET images courtesy of the Alzheimer's Disease Education and Referral Center/National Institute on Aging; Postmortem images courtesy of Edward C. Klatt, Florida State University College of Medicine

We believe the root cause of Alzheimer's pathology is a toxic interaction of a protein fragment called amyloid-β 1-42 with specific ion channels in the outer membrane of neurons. Our data show that this interaction causes an abnormal influx of calcium ions (Ca2+) into the cell, disrupting cellular machinery and inhibiting the neuron's ability to respond to incoming stimuli. Over time, the Ca2+ dysregulation effectively poisons the cell. We have been able to arrest this process by introducing small "decoy peptides" that bind Aβ1-42 and force it from its destructive shape into a benign complex with the decoy. In this article I shall summarize the current understanding of Alzheimer's disease, a few of the best therapeutic candidates, and our own work.

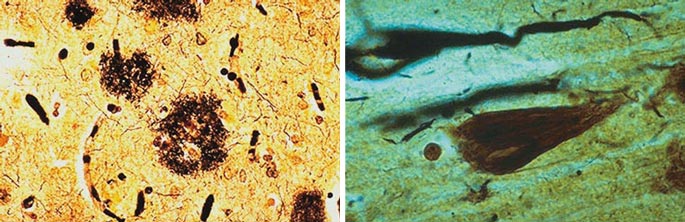

The first description of Alzheimer's disease appeared about 100 years ago, published by the neurologist Alois Alzheimer in Munich. He described the case of a 51-year-old woman with memory deficits and striking behavioral changes. Her symptoms worsened quite rapidly, and as the condition progressed she became unable to care for herself. After the woman's death five years later, an autopsy revealed extensive pathological changes: The cortex was shrunken, and there were many small, abnormal structures scattered throughout the brain. Using a silver tissue stain to visualize the structures, Alzheimer noted a profusion of extracellular senile plaques (normally found in the elderly) and never-before-seen tangles inside neurons. These tangles appeared to be made of long, knotted filaments, or fibrils, under the microscope. On the basis of these novel fibrillar tangles, plus the patient's age and the unusual number of senile plaques, Alzheimer distinguished this disease from "normal" senile dementia, a more benign and gradual age-related loss of mental function. In fact, for a long time Alzheimer's disease was referred to as pre-senile dementia, indicating that it occurred earlier than expected.

Photomicrographs courtesy of Edward C. Klatt, Florida State University College of Medicine

Alois Alzheimer noted that many of the characteristic changes in brain anatomy were concentrated in the cortex. For reasons that are still incompletely understood, some brain regions (including frontal cortex) are especially susceptible to the cellular trauma of Alzheimer's disease. This localized damage leads to a stereotyped order of decline in specific brain functions. Smell is one of the first to disappear, followed by memory, orientation and behavioral grooming, self-preservation functions. On the other hand, locomotion stays intact, distinguishing the disease from Parkinson's disease.

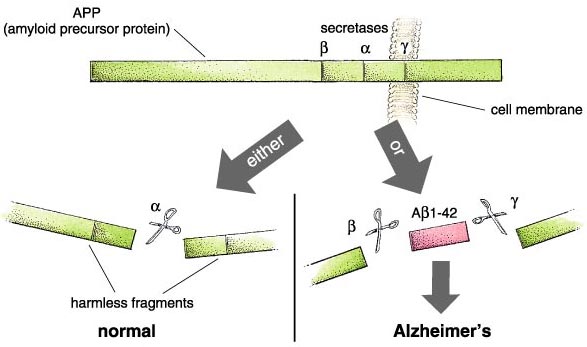

Emma Skurnick

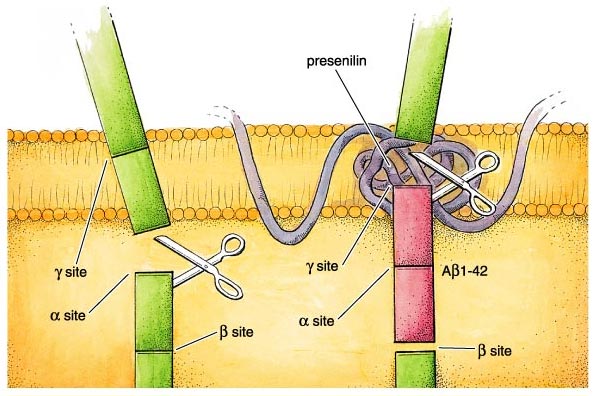

What actually goes wrong in the brain of an Alzheimer's patient? There are some half-dozen different genetic circumstances that can trigger the disease, and probably others that are currently unknown. They all lead to the same molecular pathology—the formation of aggregates of a "misfolded" fragment of a normal protein. This normal protein, the amyloid precursor protein or APP, is embedded in the outer membrane of cells in a variety of tissues. In the course of its normal function, APP is cut into segments, or peptides, at three specific sites targeted by α-, β-, and γ-secretase enzymes, respectively. During the development of Alzheimer's disease, the APP protein is cut at the β and γ sites, resulting in a fragment that folds itself into a sticky, self-aggregating shape. This peptide can be from 39 to 43 amino acids long, owing to a peculiar variability in the β-secretase cleavage site. Not all of the versions are produced in equal amounts—the so-called Aβ1—40 is most common—and some forms are worse than others, with the most toxic peptide being Aβ1-42. This fragment includes the first 42 amino acids after the β-secretase site and readily forms insoluble clumps in the brain. These aggregates are toxic and lead aggressively to the dysfunction of nearby brain cells and their consequent death and removal. Once these brain cells are gone, there is at present no way to replace them.

During much of the 20th century a diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease was difficult to confirm until the patient's brain could be examined after death—a thoroughly unsatisfactory situation. During the individual's lifetime the diagnosis was based on exclusion, since some other conditions produce similar cognitive deficits. For example, certain types of memory loss and certain behavioral changes can be caused by depression, malnutrition, medication side effects and vascular accident. The lack of rigor in diagnosis had unfortunate consequences: False positive diagnoses led to needless anxiety, whereas false negatives prevented suitable care and long-term planning.

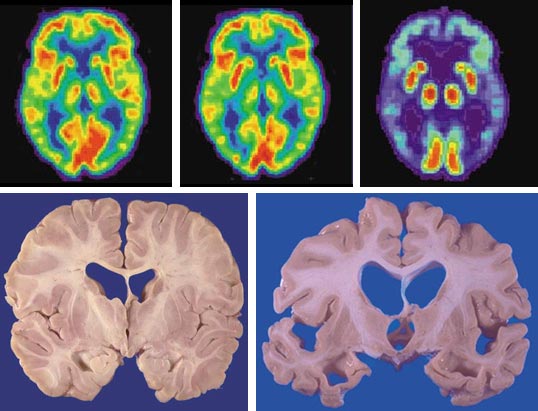

Current diagnostic criteria rest on a carefully compiled behavioral assessment scale, sometimes combined with one or more forms of noninvasive functional neuroimaging. The diagnostic scale uses as many as a dozen different measurable cognitive parameters, all of which must show considerable changes before a diagnosis is made. This scale is a highly accurate tool in the hands of a skilled physician—even without imaging data, approximately 90 percent of diagnosed Alzheimer's sufferers are confirmed at autopsy.

Emma Skurnick and Tom Dunne

Two new methods that directly examine brain activity have become invaluable tools in documenting the structural and functional changes associated with Alzheimer's disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides a detailed three-dimensional depiction of brain topography that can reveal the loss of brain tissue accompanying disease progression. The technique has become remarkably sensitive, even detecting the loss of brain volume during early stages of the disease when mild cognitive impairments might not warrant a behavioral diagnosis. Functional MRI (fMRI) and positron-emission tomography (PET) are both widely used to resolve areas of activity in the living brain. During the brain scans the subject performs a memory task. Differences between the images of Alzheimer's subjects and scans of normal brain activity can be dramatic.

Early diagnosis using these tools is important now; it will be crucial once effective therapy is available. Many of the disease symptoms are caused by the death of brain cells, and dead cells cannot be revived. Emerging treatments promise a not-too-distant future in which therapy will need to be applied before the patient becomes seriously demented. Eventually, science may perfect the use of stem cells to replace the dead brain cells, and early diagnostic screening for the disease might include genetic testing.

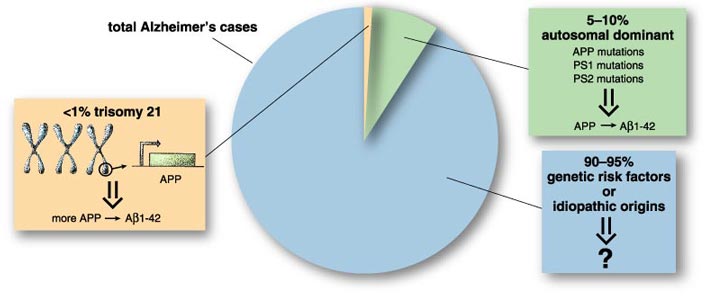

The youngest cases of Alzheimer's disease are found among people with Down syndrome, which is not usually an inherited condition. Down syndrome patients have an extra copy of chromosome 21, for a total of three; this genetic cause for Down syndrome is described as trisomy 21. Because the gene that codes for APP protein is on chromosome 21, Down syndrome individuals have more of the amyloid protein, and neurotoxic accumulation of the Aβ1-42 fragment becomes noticeable much earlier. Every person with Down syndrome has already started to develop the characteristic plaques and tangles of Alzheimer's disease by age 40.

Emma Skurnick

Some genes passed from parent to child do cause Alzheimer's disease. Fewer than 10 percent of cases can be linked to an autosomal dominant gene, where one mutant allele, or altered gene locus, is sufficient to cause the disease. This small percentage represents several different genes, found in different families but sharing a common inheritance pattern, each one causing Alzheimer's disease in that particular kindred. These individuals have relatively early onset in the 50s and 60s, and their condition deteriorates rapidly.

A much larger number of people have an inherited susceptibility to the disease, but they experience onset in their late 60s, 70s and 80s with slower progression. That leaves a sizeable proportion of idiopathic cases—ones without an identified cause, genetic or otherwise. However, every year more genetic risk factors are discovered, and it is possible that every case will eventually be traced to some genetic susceptibility. The idea offers mixed hope, as sorting out the genetics will not necessarily tell us how to intervene in the disease. For the present, only one risk factor is completely reliable: advancing age.

Why is aging such an important risk factor? To date there are only a few speculations about the mechanism of an old-age trigger for Alzheimer's disease. One of these models suggests that an age-associated decrease in the all–important, energy–containing molecule adenosine triphosphate, or ATP, is responsible. Neuronal ATP is reduced in the aging brain, and neurons need lots of it—more than most other cells, even at rest. Without ATP, the cells may be unable to reestablish their equilibrium and defend against the neurotoxic effects of the Alzheimer's peptide.

Senile plaques from postmortem Alzheimer's brains are largely composed of short amyloid peptides, as shown in 1984 by George Glenner and his colleagues at the University of California, San Diego. Identification of the amyloid peptide, originally described as "beta protein" because of its adoption of a beta-sheet conformation, soon led to the cloning of the APP gene. The relationship of toxic amyloid fragments to benign full-length APP points to an enduring question in the field: How is the poisonous peptide produced?

Emma Skurnick

In normal or young brains, the full-length membrane-spanning protein is broken down into functional fragments, including a large cytoplasmic piece used to regulate important cell mechanisms. But in Alzheimer's brains, degradation of APP takes a wrong turn. For reasons that are still not entirely clear, the relative activities of the three proteases, or protein-cutting enzymes, that cleave APP change dramatically. Dennis Selkoe at Harvard's Brigham and Women's Hospital, among others, showed that two of them, the β- and γ-secretases, become much more active, resulting in overproduction of the 42–amino acid peptide. Meanwhile, the α-secretase, which acts at a location between them, becomes relatively inactive. This is unfortunate, because cutting the precursor protein at the α site produces harmless fragments.

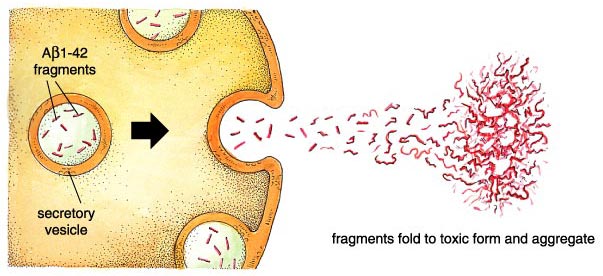

The newly cleaved Aβ1-42 peptide is immediately exported. This unique feature distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from most other neurodegenerative diseases, which act inside cells. It also simplifies potential therapies, since the helpful "drug"—an antibody, peptide or other molecule—does not have to enter a cell, where it might cause unwanted effects.

Once outside the cell, Aβ1-42 assumes a beta-sheet-containing, aggregate-prone conformation. In cell culture, the aggregated peptides cause neurons to die, and the same is true when they are injected into the mammalian brain. This cell death can occur by apoptosis (programmed cell death) or by necrosis. The former involves cell shrinking, membrane destabilization (blebbing), and DNA degradation before garbage-eating macrophage cells clean up the imploded remains. Necrosis is less tidy. Here the cell swells and explodes, releasing a witches' brew of compounds that cause the inflammation characteristic of Alzheimer's disease. The importance of blocking the products of necrosis has been emphasized recently with the finding that some anti-inflammatory medications may delay disease onset and progression.

Recently we developed a molecular model to explain the neurotoxicity of the Aβ peptide. It accounts for the known importance of protein conformation and provides a direct link between extracellular toxicity and intracellular damage, dysfunction and death.

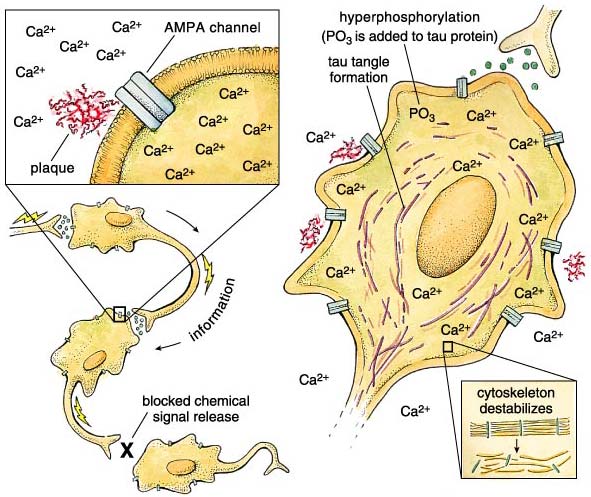

The key model feature is our observation of a selective association of aggregated Aβ peptide with specific neurotransmitter-gated ion channels in the cell membrane. These channels open in the presence of the neurotransmitter glutamate, but they also bind very specifically to an artificial glutamate analogue: α-amino-3-hydroxl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid, or AMPA. The specificity for AMPA distinguishes these channels from others that are also glutamate-regulated, and the AMPA-specific channels are the only ones affected by the Aβ peptide. In the presence of aggregated Aβ fragments—but not the soluble, nonaggregated fragments—the channels get stuck in an open position, allowing calcium ions to flood into the cell. This calcium influx disrupts cellular processes and eventually leads to cell death. In support of our hypothesis, there are reports that the AMPA channels affected in this way are restricted to the same specific areas of the brain that are involved in Alzheimer's disease.

Why is a large and lasting calcium ion influx so bad for a neuron? As it happens, Ca2+ is a vitally important signal used by dozens of systems within the cell. Local changes in cellular Ca2+ levels regulate everything from neurotransmitter release to gene expression to mitochondrial function. With such a central role, internal calcium levels are normally very tightly regulated by redundant layers of compensatory sinks, pumps and sources. But when the aggregated Alzheimer's peptide props open AMPA channels, internal calcium levels go up and stay elevated for a long time. Because of the role of calcium in neurotransmitter release, the neuron cannot respond to incoming stimuli, leading to interruptions in the flow of information within the brain. The interruption translates to cognitive deficits because of the prevalence of AMPA receptors in the hippocampus and cortex—brain regions involved in memory and critical thinking.

In addition to blocking neuronal communication, the calcium dysregulation may also underlie the second major histological finding of Alois Alzheimer: neurofibrillary tangles. These long, bundled fibers are composed of a protein called tau, which has clumped together as a result of extensive chemical modification by protein kinase enzymes. Kinases control many cellular events by adding phosphate groups to proteins, and calcium is a common kinase trigger. Consequently, when calcium levels stay up for long periods of time, kinases are overactivated, and the tau protein becomes a target for phosphate addition. In this state tau is said to be hyperphosphorylated. Hyperphosphorylation not only causes tau to clump together, but it also prevents tau from performing its normal job: stabilizing microtubules that give the cell its structural integrity. The loss of microtubule integrity further damages the neuron, and this damage is proportional to the clinical progression of the disease. The extent of tau modification correlates with the degree of dementia, confirming that brain cells filled with hyperphosphorylated tau (and, by inference, unstable microtubules) are dysfunctional. Between the loss of cytoskeletal support and the calcium flood, the cell loses control of basic metabolic processes and dies (necrosis) or commits suicide (apoptosis).

Thirty years ago, studies of degeneration patterns in Alzheimer's disease identified substantial decreases among groups of neurons in the basal forebrain. These cells all used the transmitter acetylcholine, and their loss meant that less acetylcholine was being released at their former terminals in the cortex. The finding was important because cholinergic neurons in the cortex are involved in regulating attention, the first stage of learning and memory.

This knowledge led to the first (and only) Federal Drug Administration–approved drugs for Alzheimer's disease treatment, marketed under the trade names Aricept, Cognex and Exelon. All three work by prolonging the effects of individual acetylcholine-release events. They do this by inhibiting the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, which normally breaks down the neurotransmitter in the space between cells. This breakdown process goes on unabated even when there is too little acetylcholine being released, as is the case in Alzheimer's disease. By preventing acetylcholine metabolism, the levels of free neurotransmitter can be artificially raised. Unfortunately, clinical trials show that the improvement in memory is small and transient, whereas the side effects can be troublesome. In Europe the compound memantine, an inhibitor of a different (nonAMPA) glutamate-sensitive channel, is used for "age-related dementia" with some reported benefits.

Since the overproduction of the noxious Aβ1-42 fragment is now considered the root cause of Alzheimer's disease, the two enzymes that produce the peptide have become prime targets for therapy. The β-secretase enzyme produces the amino terminus, and the γ-secretase enzyme cleaves the carboxyl terminus of the peptide from the amyloid precursor protein.

The potential value of therapies based on the pattern of protein cleavage (or proteolysis) of APP is illustrated by the fact that no fewer than five Alzheimer's research groups in 1999 and 2000 independently identified the β-secretase enzyme—now called BACE1. Importantly, the β-secretase protein seems to be confined to specific regions within the central nervous system, making it a good therapeutic target. The hippocampus and cortex show the highest expression levels, and peripheral tissues have only trace amounts. As a consequence of its tight localization, systemic inhibition of the enzyme might be possible with relatively few undesirable side effects.

Additionally, mice without the BACE1 gene are healthy, reinforcing the enzyme's status as an exceptional pharmacological target. Indeed, powerful inhibitors of β-secretase have already been reported, but they are large molecules, making them unsuitable for therapeutic use. As a cautionary note, there has been some early evidence that β-secretase inhibitors can also interfere with other enzymes that cut proteins, leading to unwanted complications. Thus, more work is needed (and is certainly being done) to develop a smaller and more specific inhibitor.

Emma Skurnick

The second critical enzyme, γ-secretase, has its own unusual properties that may aid in tailoring specific therapies. As shown in the figure, the γ cleavage site lies within the membrane-spanning domain of APP, meaning that the γ-secretase catalytic domain must work in the hydrophobic lipid layer of the cell membrane. Yet the chemistry of protein digestion requires the addition of water to cleave the peptide bond. How is this done? The mechanism is incompletely understood, but it involves several other proteins besides APP and the γ-secretase.

Two other molecules in the proteolytic complex are central: the so-called presenilins, PS1 and PS2. The presenilins have attracted attention because of the frequency with which mutations in the genes coding for PS1 or PS2 cause heritable, early-onset Alzheimer's disease. More than a hundred presenilin mutations are known, but they all seem to cause an increase in the Aβ1-42 product of amyloid precursor digestion. Fortunately, these sorts of autosomal dominant mutations occur only rarely.

Gamma secretase is also a less desirable candidate from a genetic standpoint. In mutant animals without the gene, the absence of the enzyme prevented normal development, and the embryos died. This finding hasn't deterred the concerted effort to identify γ-secretase inhibitors that might reduce levels of Aβ1-42 in the adult brain. Yet it remains to be seen whether a decrease in beta amyloid will lead to restoration of lost function in animal models and, of course, in people.

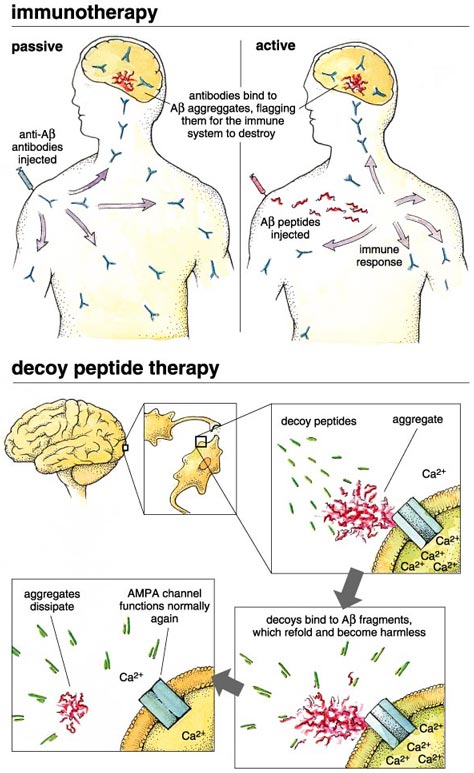

Another approach to interrupting the disease harnesses the patient's immune system to identify and remove the toxic Aβ1-42 aggregates. In principle this can be done either by active or by passive immunization. In the former case, the patient receives an injection or nasal-spray application of the Aβ peptide, leading to an anti-amyloid immune response. Both injection and spray strategies are being pursued, and clinical trails have begun. Passive immunization bypasses the beta amyloid protein, using instead antiserum that has already been produced in response to beta amyloid. This is also being pursued actively.

Emma Skurnick

Part of the excitement about immunotherapy was based on successful animal studies, including one using transgenic mice engineered to overexpress human APP sequence. As described by Dennis Selkoe of Harvard and Dale Schenk with Elan Pharmaceuticals, the mice showed a strong immune response to the Aβ peptide, leading to a substantial reduction in the accumulation of beta protein and a partial elimination of memory deficits.

Such results held great promise for the future of this therapeutic approach. Unfortunately, the anticipation has sharpened recent disappointment over the termination of a large, international clinical trial. About five percent of 375 patients enrolled in the trial developed severe brain swelling after being inoculated with the Aβ peptide. This inflammation could have been due to a mistake in exactly which part of Aβ to use, or perhaps the peptide needed to be refined more cautiously, or the immunization procedure itself may need to be altered. However, other trials using other protocols are proceeding, and the results are eagerly awaited. Clinical trials of passive immunization have also begun, but the study authors have not yet published results. Passive immunization requires a continuing regimen of injections of the antiserum preparation, a feature that had been seen as a disadvantage but may yet prove superior if it bypasses the complications of Aβ inoculation.

A novel approach to Alzheimer's therapy is needed. Although secretase inhibition and immunotherapy promise to lead to beneficial symptom reduction, they do not yet promise complete elimination. Each treatment appears to have some side effects, and these may limit the allowable range of therapeutic dosages.

One can envisage a drug that would eliminate the neurotoxicity of the aggregated Aβ1-42 peptide itself. Such a drug would have to be given early in order to "detoxify" the gradually accumulating aggregated Aβ peptide before any permanent damage is done to neurons. After all, we do not yet know how to replace dead or dying neurons (although replacement by stem cells might be possible eventually).

James Knowles/Corbis Sygma

The approach taken in my laboratory is to present the aggregating Aβ1-42 peptide with a small molecule that binds to the peptide and forces it to assume a nontoxic structure. My colleagues and I have done this with 16 small peptides (5, 6 or 9 amino acids long), which we call "decoy peptides." They are selected from large libraries of protein fragments by their ability to form a tight association with tagged Aβ1-42. We have found that when presented to the Alzheimer's peptide during aggregation, our decoy peptides completely eliminate the neurotoxic effects, and Aβ1-42 no longer causes massive calcium influx into neuronal cells. We are very excited about these results, and because the peptide binding is so specific, we anticipate a small chance of harmful side effects. These peptides are good candidates for further development, and we have constructed them from d-amino acids (the unnatural form of amino acids) to resist digestion in the body, but a big question remains: Will they get from the gut to the brain? The answer remains to be seen (or engineered).

In old age the brain does not work as well as it used to do. We forget keys and appointments; words hide on the tip of our tongue. Is this a slow form of Alzheimer's disease? Lurking in the backs of our minds, but not often discussed, is the idea that this disease is just a greatly accelerated version of "normal" brain aging. Maybe this would be a good thing, if proved true: If normal aging and Alzheimer's disease shared the same mechanism, then perhaps an Alzheimer's therapy could also treat the forgetfulness that everyone develops with age. It wouldn't help us live longer, but might help us live better!

Although nobody can predict the future, claiming that a cure for Alzheimer's disease is around the corner, we should be hopeful. Our fundamental knowledge of this disease has increased enormously in recent years through the hard work of many, many scientists and clinicians. This mechanistic understanding enables us to develop detailed new strategies to interrupt the disease. Some of these are described above, but who knows what else is waiting to be found? Serendipity is the most powerful scientific tool, and we must be ready to use whatever turns up.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.