Alpha and Omega, Universe on a T-Shirt, Explorers and Natives in the Polar North and more . . .

By David Schneider, Rosalind Reid, Greg Ross, Michael Szpir

Short takes on nine books

Short takes on nine books

DOI: 10.1511/2004.46.0

These are heady days for cosmology. For the first time we really can hear the music of the spheres—the oscillations of the early universe, captured in the cosmic microwave background. The end is in sight, too; in the final days of the last millennium, we learned from supernovae that "our destiny is a death by ice."

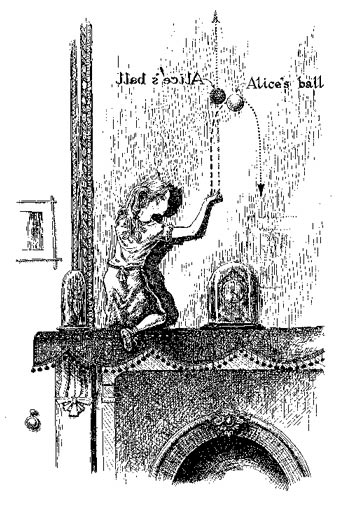

Among those bowled over by these developments is science journalist Charles Seife, whose page-turner Alpha and Omega: The Search for the Beginning and End of the Universe (Penguin, $24.95) is notable among the new books interpreting the deluge of important new information and ideas about the universe. In stylish, inviting prose, he conveys the surprise and drama of recent discoveries such as the accelerating expansion of the universe. He even provides his own list of Nobel contenders. Matt Zimet's charming ink sketches help the reader to ponder tough concepts (such as the violation of mirror symmetry, or parity, at left)—and to hang on while riding with surprised scientists through time, energy, space and cosmic history.—R.R.

While astronomers are listening to the music of spheres, some theoretical physicists believe they've discerned the unifying harmonies of an exotic string symphony—the possibility that the vibrations of infinitesimally tiny loops of string are the source of all matter and energy.

From Universe on a T-Shirt: The Quest for the Theory of Everything.

In Universe on a T-Shirt: The Quest for the Theory of Everything (Arcade, $24.95), Canadian science journalist Dan Falk describes the efforts of string theorists and others to resolve the contradictions between quantum mechanics and relativity. The first U.S. edition of a book published in Canada in 2002, T-Shirt lacks coverage of significant (and confounding) developments in string theory since Brian Greene's The Elegant Universe captured the public imagination in 1999. But it's a workmanlike piece of journalism. Mixing simple explanations and personal profiles with touches of philosophy and whimsy (cartoon, right), T-Shirt gives a highly accessible introduction to some tough and important physics.—R.R.

In the lavishly illustrated Ultima Thule: Explorers and Natives in the Polar North (Norton, $75), geomorphologist Jean Malaurie chronicles 170 years of arctic exploration by European and American adventurers. Their stories show courage, gallantry and almost unimaginable sacrifice, but to Malaurie's sensitive eye their glory is clouded by cultural arrogance.

From Ultima Thule: Explorers and Native in the Polar North.

Throughout the 1800s, European expeditions disdained the help of native Eskimos and descended instead into rivalries, mutinies, assassinations, suicide and betrayal. British explorers would suffer scurvy rather than eat the food of "savages." They shivered in military tents and hauled their ponderous sledges with men rather than "picturesque" native dogs. The Inuit, who offered food, friendship and 6,000 years' experience living at high latitudes, gradually became convinced of their own cultural and technological superiority.

Not until 1891, with Robert Peary, were the Eskimos significantly involved in expedition efforts, and they were treated as equals finally in 1905, by Knud Rasmussen (left). By 1950 Malaurie was traveling alone among the natives, adopting 90 percent of their diet; he made 31 successful expeditions in this way, occasionally passing the sites of his predecessors' disasters. "Vanity and jealousy," he comments philosophically, "the levers of history."—G.R.

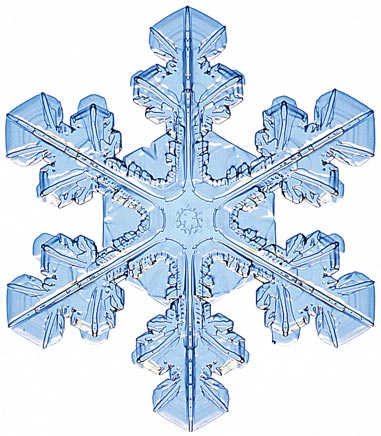

Snowflakes have an impressive scientific pedigree. Johannes Kepler studied their sixfold symmetry, René Descartes investigated their crystal structure, and Robert Hooke sketched them using an early microscope. The Snowflake: Winter's Secret Beauty (Voyageur Press, $20), with text by Caltech physicist Kenneth Libbrecht and stunning photography by Patricia Rasmussen, notes that they also have sublime appeal: "A snowflake is a temporary work of art."

Each flake starts as a nucleus of ice that grows into a minute hexagonal prism. Sprouting from the hexagon's corners, the arms develop nearly identically as the flake drifts through variations in temperature and humidity. (A typical flake falls 10,000 feet and might float for hours before you catch it on your tongue.)

From The Snowflake: Winter's Secret Beauty.

Libbrecht offers an accessible primer on the molecular foundations of crystal geometry and puzzles out snowflakes' intriguing combination of symmetry and complexity. For someone setting out on a winter walk with a good magnifying glass, the book would make a fascinating field guide.

Are any two flakes alike? The atmosphere can make a million billion snowflakes per second. Yet Libbrecht concludes that, due to molecular imperfections and stray isotopes, each flake is probably subtly different from all the others. He’ll keep studying, though: "One does not easily become bored looking at snowflakes."—G.R.

From A Field Guide to Bacteria.

During a field trip in 1980, biologist Betsey Dexter Dyer became intrigued by the idea that one didn't need a microscope to identify bacteria—a number of macroscopic field marks provide ample clues to anyone who cares to look . . . or smell. And so was born A Field Guide to Bacteria (Cornell, $26 paper), a book for amateur naturalists who want to identify the visible manifestations of the tiny organisms that make up the bulk of the planet's biomass. Dyer introduces readers to a "bacteriocentric" worldview and then goes on to describe various habitats worth exploring: hot springs, kitchens, zoos, estuaries, parks, deserts, damp walls—just about anywhere, actually. But the greater part of the book describes the various taxonomic classes of bacteria—proteobacteria, cyanobacteria and many others—telling where these might be found, what they look like and how they smell. Among the more interesting microbes are the gram-positive bacteria that add flavor and color to foods: cheeses, beers, wines, sourdough bread and pickled vegetables. With a bacteriocentric point of view, you may never look at a piece of cheese the same way again.

Strong-smelling cheeses (such as Limburger) have a pink-orange-red surface produced by the gram-positive Brevibacterium, which is also involved in the production of foot odor (above).—M.S.

Identifying raptors can be tricky, partly because they are wary and often must be viewed at a distance, but also because they tend to be darkly colored, exhibiting subtle differences in plumage. Two new guides from Princeton University Press by Brian K. Wheeler, Raptors of Eastern North America ($45) and Raptors of Western North America ($49.50), attempt to solve the ID problem by providing exceptionally detailed species accounts of the diurnal birds of prey—hawks, eagles, kites, falcons and vultures; included are descriptions of ages, molt patterns, subspecies and color morphs. The scope is ambitious: Each guide has hundreds of photographs and dozens of maps. However, there is significant duplication between the two volumes, and some readers may question the wisdom of owning both. Many birders prefer illustrations to snapshots, but Wheeler's wonderful images, showing many variations in plumage, should win them over.

From Raptors of Western North America.

Above, an adult Swainson's hawk (Buteo swainsoni) stands on one leg while stretching the opposite leg and wing prior to taking flight, and below, a juvenile sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) fans out its tail, which acts as a brake and a rudder during a banking turn.—M.S.

From Raptors of Eastern North America.

Years ago, when there were fewer lawyers around, those writing about science experiments for students or grown-up amateur scientists had an easier time: These authors (and their publishers) didn't worry too much about possible injury and consequent legal actions. Today, guides such as Neil A. Downie's Ink Sandwiches, Electric Worms and 37 Other Experiments for Saturday Science (The Johns Hopkins University Press, $18.95 paper, $45 cloth) and Simon Quellen Field's Gonzo Gizmos: Projects and Devices to Channel Your Inner Geek (Chicago Review Press, $16.95) must, understandably, steer well clear of projects that are potentially dangerous. Despite this handicap, both authors come up with much material. Of the two, Downie's book appears the more polished, and only it consistently provides discussion of the equations governing the physics or chemistry that is demonstrated. Downie is generally well versed in the areas of science on which he touches, so his commentary and references are valuable. Yet the projects Downie details are on the whole much less intriguing than those Field offers.

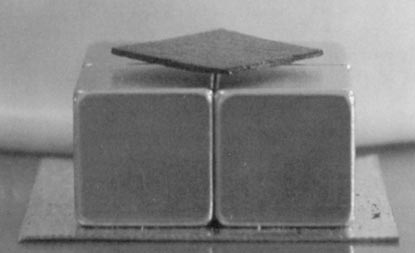

From Gonzo Gizmos: Projects and Devices to Channel Your Inner Geek.

Downie's ink sandwiches and electric worms, for example, are uninspired compared with Fields's CD-based spectroscope or the procedures Field gives for diamagnetic levitation (floating a small piece of pyrolitic graphite, for example, shown at right).—D.A.S.

Nanoviewers: Rosalind Reid, Gregory Ross, David A. Schneider, Michael Szpir

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.