The Other Honey

By Elsa Youngsteadt

A new research center in Ghana adds to the global growth of stingless-bee beekeeping for pollination and honey

A new research center in Ghana adds to the global growth of stingless-bee beekeeping for pollination and honey

DOI: 10.1511/2012.95.121

In rural Ghana, stingless bees are well known as useful animals. Farmers raid natural hives to collect honey, which they use to treat ailments from eye infections to asthma. Many say the bees improve crop yields, and people refer to different species by their indigenous monikers. (The tifuie, for instance, is named after its tendency to get caught in people’s hair.) Despite farmers’ familiarity with these small bees, however, “they had no idea that they could bring them home and culture them and keep them,” says entomologist Peter Kwapong.

Kwapong directs the International Stingless Bee Centre, a new hub for research, outreach and education at the University of Cape Coast in Ghana. Over the past six years, the center has developed methods for propagating Ghana’s native stingless bees in artificial hives. And it has trained more than 200 West African farmers and extension workers to do the same. “People are catching on,” Kwapong says. They’re beginning to manage the bees as pollinators and as a sustainable source of honey and other products.

“It’s got tremendous potential,” says Sam Droege, a biologist with the United States Geological Survey, who visited the fledgling center in 2009. “You don’t tame a group of animals very often, and here, all of a sudden, is an entirely new group of animals that are now available for agriculture.”

The stingless bees, although related to the better-known honey bees, make up their own distinct tribe called the Meliponini. All of the world’s several hundred species are tropical or subtropical and distinguish themselves by having vestigial stings. No one knows exactly why the lineage lost the ability to inject venom, but colonies ably defend their nests by biting, secreting noxious chemicals and even trapping small intruders with sticky plant resins. Where humans are concerned, however, many species are docile, or at least harmless. “Their strategy for repelling people is irritation,” Droege says. “They don’t sting, but they climb all over you … poking in your eyes and crawling in your ears.”

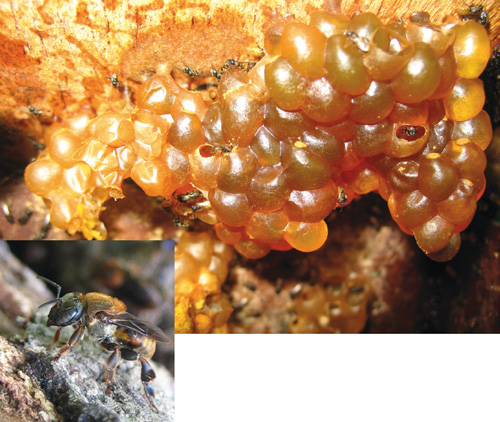

The absence of a sting is convenient, but it’s the bees’ honey that earned them the notice of indigenous cultures throughout the tropics. Inside their nests—typically in hollow trees or other cavities—the bees stockpile both honey and pollen in lumpy little “pots” fashioned from cerumen, a mixture of beeswax and plant resins. The insects are active year-round, and use the stored food to provision developing young when flowers are scarce.

Stingless-bee honey varies widely in flavor and color, depending on the bee species and the flowers they visit; the substance is variously described as sweeter, sharper, more bitter or more alcoholic than honey-bee honey. With up to 40 percent water content, it is runnier and more apt to ferment once collected. And it’s harder to get: A typical colony produces only 1 to 3 liters of honey per year, compared to 50 or more for honey bees.

Nevertheless, especially where honey bees aren’t native, stingless-bee honey is traditionally sought as both a sweetener and a medicine. Indeed, in-vitro studies of the honey and cerumen of several Australian, Neotropical and Asian species confirm their antimicrobial properties—although the strength and antibiotic spectrum of these products varies with species, geography and, most likely, which plants the bees use.

Few researchers have extended these antimicrobial studies to animal models, but Kwapong and his colleagues recently did so. Noting the practice among rural Ghanaians of treating eye infections with drops of stingless-bee honey, they tested Meliponula honey as a treatment for bacterial conjunctivitis in guinea pigs. The results, in press at the Journal of Experimental Pharmacology, suggest that it works.

Although people have foraged for stingless-bee honey for centuries—if not millennia—only a few cultures developed stingless-bee beekeeping, or meliponiculture. The practice was most advanced among the Maya of the Yucatán peninsula, who documented their methods pictographically in a codex that dates to around or before the time of the Spanish Conquest. These beekeepers housed colonies of Melipona beecheii in hollow logs with stone caps, periodically collecting honey and dividing colonies to increase their population.

That traditional practice lives on today—barely. It has declined steeply over the past three decades due to cultural and environmental changes such as deforestation and competition with introduced honey bees. At the same time, however, researchers in other regions have discovered that their own local stingless bees can be efficiently kept in artificial hives. Research and education groups dedicated to modern meliponiculture have sprung up in Australia, Colombia, Costa Rica and Brazil, to name a few. In each region, the invention of easily managed hive boxes has been a precursor to the popularity of stingless-bee beekeeping.

In Australia, most colonies are kept more or less as pets. But Tim Heard, an entomologist at Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, says that stingless-bee pollination could also become a “significant industry.” More than 20 species, in Australia and elsewhere, have been found to pollinate at least one crop each, including macadamia nuts, coffee, avocado, tomato, cucumber and strawberry. Several species will forage and pollinate inside greenhouses.

That economic potential has spurred the growth of meliponiculture in the Neotropics, where rural farmers often keep stingless bees for supplemental income. In Brazil, multiple university-government partnerships have actively developed and promoted the practice; an informal census in 2005 found hundreds of beekeepers managing nearly 3,000 colonies of 23 stingless-bee species.

And it was in Brazil that Peter Kwapong, too, learned about meliponiculture. Visiting the University of São Paulo during a 2004 conference, he toured a bee-research lab that kept hives of stingless bees. He immediately wondered whether Ghana, with its similar climate and habitats, might have suitable species too. Back home, he organized a survey of the country’s stingless bees, found 12 species, and applied for funding to study them and develop methods for their husbandry.

Six years after receiving that first grant, the International Stingless Bee Centre has a functional infrastructure in the agricultural village of Abrafo and has established seven stingless-bee species in customized hives. Kwapong and his colleagues offer free training workshops to regional farmers and published their manual, Stingless Bees: Importance, Management and Utilisation, in 2010. (It’s also available online.)

As one of the newest outposts of meliponiculture, on a continent where its potential is essentially unexplored, the center still has a lot of work to do. Among other things, Kwapong plans to investigate more medicinal uses of stingless-bee honey and cerumen and explore the insects’ utility as crop pollinators.

Whether stingless-bee beekeeping will really catch on in Ghana is still an open question. But on a global scale, as honey bees begin to falter under the weight of hive pests and disease, stingless bees may be the pollinators—and honey makers—to watch.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.