This Article From Issue

November-December 2023

Volume 111, Number 6

Page 377

PERIPHERY: How Your Nervous System Predicts and Protects Against Disease. Moses V. Chao. 192 pp. Harvard University Press, 2023. $29.95.

In 2015, thousands of researchers descended on a Chicago convention center for a gathering of the Society for Neuroscience. On the event’s second-to-last afternoon, Francis Collins, then-director of the National Institutes of Health, rose to the podium amid a standing-room-only audience. The brochure promised a lecture about brain research.

By the time the talk ended, though, Collins was advocating for his listeners to explore something entirely different than what had been billed. The community of neuroscientists, he argued, should train its eye on the many neurons and networks that sit outside the brain and spinal cord. There, in the peripheral nervous system, lay some of the body’s most important, undiscovered clues to certain illnesses.

Moses V. Chao, a professor at New York University and a former president of the Society for Neuroscience, was in the audience that day. In his debut book, Periphery: How Your Nervous System Predicts and Protects against Disease, Chao heeds the call from the Chicago convention. His book is a celebration of the peripheral nervous system, a 192-page biography of an underappreciated, overshadowed body part.

Wikimedia Commons

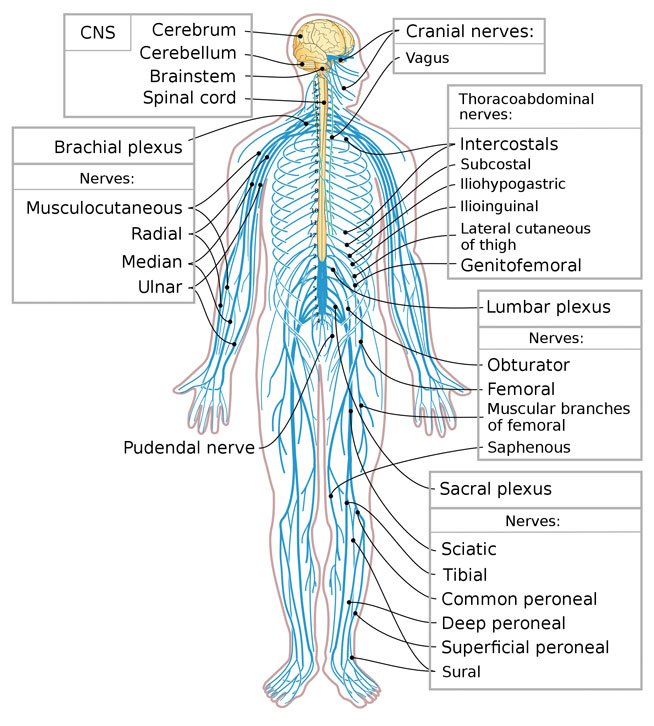

The peripheral nervous system includes all nerves outside the brain and spinal cord. This definition is misleading in its simplicity; in part because those nerves take on such varied assignments. They carry sensory information to the brain, convey motor commands from the brain, and direct the automated functions of the heart, gut, and other organ systems.

In Periphery, Chao argues that these nerves are under-recognized sensors and controllers of human health and disease. To make his case, he begins by explaining how the peripheral nervous system evolved long before the brain, in a tiny worm that roamed the deepest seas 600 million years ago. After touching on the gut-brain connection and the role of pain-sensing neurons, the bulk of Chao’s discussion focuses on the peripheral nervous system’s possible role in Parkinson’s disease and three other diseases.

In the midst of peripheral nervous system dysfunction, we just might find a cure for diseases that, on the surface, appear to simply be problems of the brain.

Although we think of Parkinson’s disease as being a problem in the brain—particularly in the deep cerebral regions that modulate movement—Chao writes convincingly that the condition may actually begin in the nerves of the gut. One of the earliest symptoms of Parkinson’s disease is constipation, which often starts years before the stereotypical trembling and stiffness. Lewy bodies, the microscopic hallmark of Parkinson’s disease in the brain, can also be found dotting the nerves that run along the gastrointestinal tract. Patients who have undergone an appendectomy are less likely to develop Parkinson’s disease, suggesting that the vestigial appendage may be an early pathologic hideout. The vagus nerve even serves as a likely suspect when it comes to explaining how a brain disease could start outside the head. This beefy structure, which runs from the abdomen into the skull, may serve as an anatomical highway for pathologic proteins to make their way from gut to brain.

Chao eventually asserts that the peripheral nervous system has been taken for granted because its work is done subconsciously. When we pet a dog, we don’t have to tell the cells in our fingertips to communicate the feeling of fluffiness to our brain. But when these processes go awry, producing chronic pain or opening the gates for neurodegeneration, we should pay attention. Chao claims that, in the midst of peripheral nervous system dysfunction, we just might find a cure for diseases that, on the surface, appear to simply be problems of the brain.

Periphery moves at a rapid clip, touching on many topics, perhaps at the expense of extended discussion, but it still stops along the way for brief portraits of some of the greatest researchers in the history of neuroscience. Jean-Martin Charcot coined names for at least 12 neurologic disorders, including multiple sclerosis, Tourette syndrome, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A talented sketch artist, Charcot discerned disease patterns by seeing commonalities in his patients’ postures and expressions. Rita Levi-Montalcini, another scientist portrayed in the book, conducted research in a bare-bones laboratory in her bedroom during World War II, when she was prohibited from working in Italian universities because she was Jewish. She went on to win a Nobel Prize for discovering a protein that helps nerves grow. Although the subtitle of Periphery makes clear that science is the main focus, rather than the scientists, the recurring cast of characters enriches the text and conveys how interconnected the world of neuroscience really is.

Chao’s book is a sweeping tour that caters primarily to those with a background in neuroscience. The text moves quickly from one topic to the next, often delving into arcane medical details, so lay readers may find themselves adrift amid the terminology and the nonlinear narrative. Nevertheless, Chao proves to be a capable guide, and at many points it feels as if he is a personal mentor sitting at the front of a small classroom, expounding on his years of experience.

The final note in Periphery feels almost futuristic. Efforts to induce neurons in the brain to regenerate have proven slow-moving despite significant funding, in part because these nerves produce proteins that impede regrowth. For the solution, Chao proposes we look to the peripheral nervous system, where damaged neurons regrow successfully all the time. “The periphery holds the answers for regeneration,” he states passionately, adding later that he sees the peripheral nervous system as the key to extending lifespan. Let’s hope he’s right.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.