A Bad Deal for Early-Career Researchers

By David Samuel Shiffman

Employers market unpaid internships as a path to high-paying science careers, but they are actually associated with lower future earnings.

Employers market unpaid internships as a path to high-paying science careers, but they are actually associated with lower future earnings.

For many people, a career working with wildlife is a lifelong dream. Unfortunately, because so many people have the same dream, finding a job in this field can be extremely competitive. For recent college graduates hoping to get a foot in the door, it can be tempting to take unpaid or even pay-to-participate internships, which promote themselves as providing hands-on training and experience. One such job that has been widely advertised on social media charges “volunteer interns” nearly $2,000 a month, and that’s after participants spend more than $1,000 to fly to the work site on another continent.

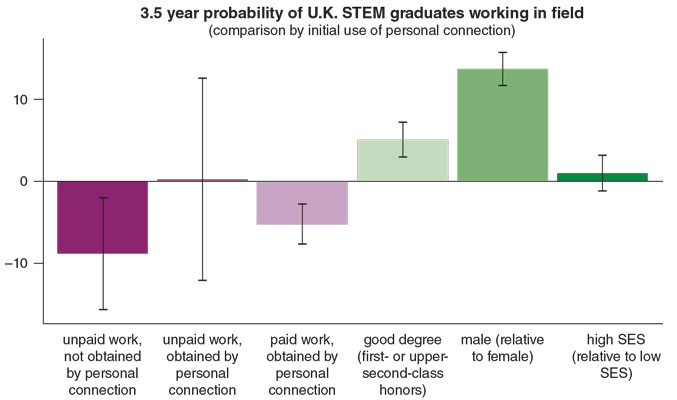

The problem here is obvious: Not everyone can afford to work for months with no pay, which gives affluent students an unfair advantage. This inequity exacerbates existing diversity issues in science. But do these unpaid positions live up to their claim of helping participants obtain high-paid positions in the field? There are certainly anecdotal examples of an unpaid internship leading to a high-profile STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) career. But a new analysis in the journal PLoS One finds a correlation between participation in unpaid internships and lower future earnings. Furthermore, those who worked as unpaid interns were more likely to leave STEM fields altogether.

The study analyzed data from more than 25,000 individuals who had graduated with STEM degrees from colleges and universities in the United Kingdom in 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009. The U.K. Higher Education Statistics Agency surveyed participants six months after graduation and followed up three years later. Those who had been doing unpaid work six months after graduating had a significantly (22.5 percent) lower annual income than those who had been doing paid work. Importantly, the study found that women are more likely to take unpaid positions than men, thus putting them on the path for lower future earnings and perpetuating the wage gap.

Auriel Fournier, currently the Director of the University of Illinois’s Forbes Biological Station and the lead author of this new analysis, is a critic of unpaid wildlife ecology internships. In 2015, she coauthored an editorial in the Wildlife Society Bulletin bluntly titled: “Volunteer Field Technicians Are Bad for Wildlife Ecology.” At the time, her arguments were moral in nature, but after studying the trajectories of tens of thousands of early-career scientists, she now has data to back up what she and others have long claimed.

Adapted from Fournier AMV, Holford AJ, Bond AL, Leighton MA (2019) Unpaid work and access to science professions. PLoS ONE 14(6): e0217032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217032

“Taking unpaid work right after finishing university is associated with lower earnings and lower persistence in STEM when compared to taking paid work,” Fournier said, pointing out that working long hours for no pay can cause stress that leads to burnout and to quitting the field entirely.

Fournier’s new paper shows that there are a lot of factors at play in each graduate’s career trajectory. For example, those with a relatively high socioeconomic status and those who used preexisting personal connections to find unpaid internships were not much less likely to persist in their scientific career. However, these people are already well-represented in STEM fields, whereas unpaid work shuts out those with more diverse backgrounds who cannot afford to support themselves without income—the very people that proponents of increased diversity have been attempting to recruit. Furthermore, the lower future earnings are true across all categories.

Fournier notes that advocates for unpaid internships in her field claim that taking such a position shows dedication to pursuing a career in wildlife ecology. “This may be true if everyone was equally financially able to make that choice, but we know that isn’t the case. We know that financial resources are not equally spread across society,” she said. “There are lots of folks who are very dedicated who don’t have the resources [to take unpaid work].”

Unpaid internships in wildlife ecology are not a new problem. Darroch Whitaker, an ecosystem scientist with Parks Canada, wrote an editorial critical of this practice in Conservation Biology in 2003. Regarding Fournier’s paper, Whitaker said:

When I wrote about this problem, I did it from a personal place. I had witnessed firsthand the emotional and economic hardship this practice was causing for many early-career professionals. I’m pleased to see the paper by Fournier and her colleagues, which relies on large-scale survey data. Their analysis is carefully thought out and thorough. I wasn’t surprised to see that they found that benefits to entry-level professions were equivocal. I get the strong feeling that most of the reasoning used to bolster this practice consists of arguments of convenience that are uncritically embraced by those who benefit from taking on unpaid and underpaid laborers.

Not everyone can afford to work for months without pay, giving affluent students an unfair advantage.

One argument in favor of unpaid internships is simple: There just isn’t enough money to go around. Fournier is sympathetic to this argument. “I appreciate that many of us are facing difficult budget choices, and that paying everyone who works on a project means that there is less money available for something else,” she says. “These are valid concerns, but if we truly care about the future of science, we need to make changes, and some of those changes involve making entry-level positions in science accessible to everyone, regardless of their financial background.”

To be sure, there are different kinds of unpaid internships. Some are offered at a university for students in that specific institution and offer students the chance to earn course credit or to run their own research projects—something that’s undeniably professionally valuable and may even be a graduation requirement for certain programs. Others are unaffiliated with any kind of credible research project or institution of higher learning and may only accept applicants who already have a degree. Participants may be required to pay for their own travel, room, and board just to fill scuba tanks, cut bait, clean glassware, or serve as a notetaker for paid researchers.

“This may be an issue where many of us don’t have the power or authority to make changes right now,” Fournier said. “But we can all change the way we talk about dedication, and we can stop tying dedication to unpaid labor. And we can all talk to our professional societies and granting agencies about their policies, and encourage them to change policies if needed.”

Fournier has advice for students considering taking one of these unpaid positions. “Your labor has value, and you have value as a person and as a part of the scientific community,” she said. “Our work to date does not support the idea that taking unpaid jobs pays off in the long run. I’m sure there are exceptions to this, and I won’t tell anyone what choices they should or should not make for themselves, but don’t assume that taking an unpaid job will pay off long term.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.