The intestine is not a privileged organ in the body: We can experience abdominal pain during exercise, for instance, because the body will shunt blood from the intestine to the heart, brain, and bigger muscles. Even the most fit athletes can experience intense cramps for this reason, because the body is prioritizing other organs in need. However, this activity can lead to damage, in what’s called intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Liara Gonzalez, assistant professor at North Carolina State University, researches how this intestinal injury occurs, but also how the intestine can regenerate because of the possible presence of reserve intestinal stem cells. Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society (Sigma Xi is American Scientist’s publisher) hosted Gonzalez for the monthly Science by the Slice lecture event. You can find the recorded talk below, or scroll down to the end to view a Twitter thread of talk highlights, authored by Kirsten Giesbrecht, an intern with Science Communicators of North Carolina.

Gonzalez was born on the outskirts of New York City, but then experienced a different style of life when her family moved to a small farm in the northeast corner of Connecticut. No one in her family had the expertise to run a farm, but her parents bought a pregnant horse, and that experience led Gonzalez on the path to veterinary medicine. Gonzalez’s first love has always been large animal models, but as her research develops, she sees a future where intestinal disease can be treated equally for both animals and humans.

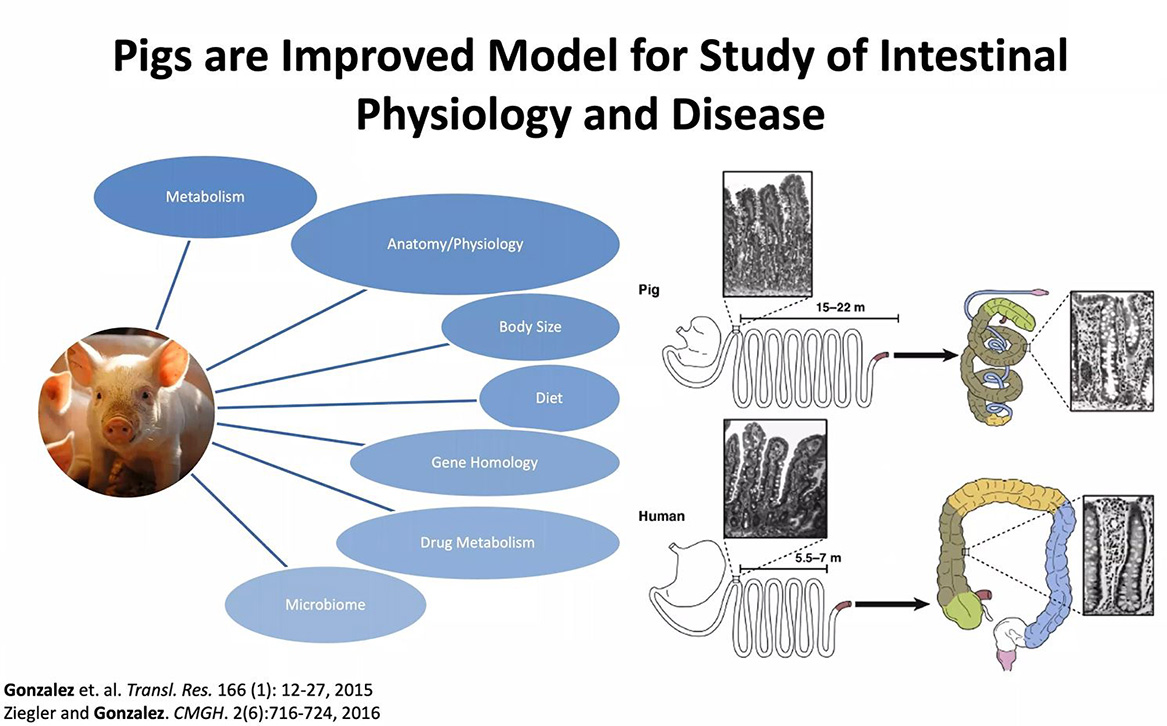

In clinical research, typically mice are the first animal model considered. But Gonzalez’s background in large animal models prompted her instead to use pigs, as a model more similar to humans when studying intestinal physiology and disease. Despite similarities between pigs and humans, there are anatomical differences in the intestine, as shown in the image below, which Gonzalez has to take into account in her research.

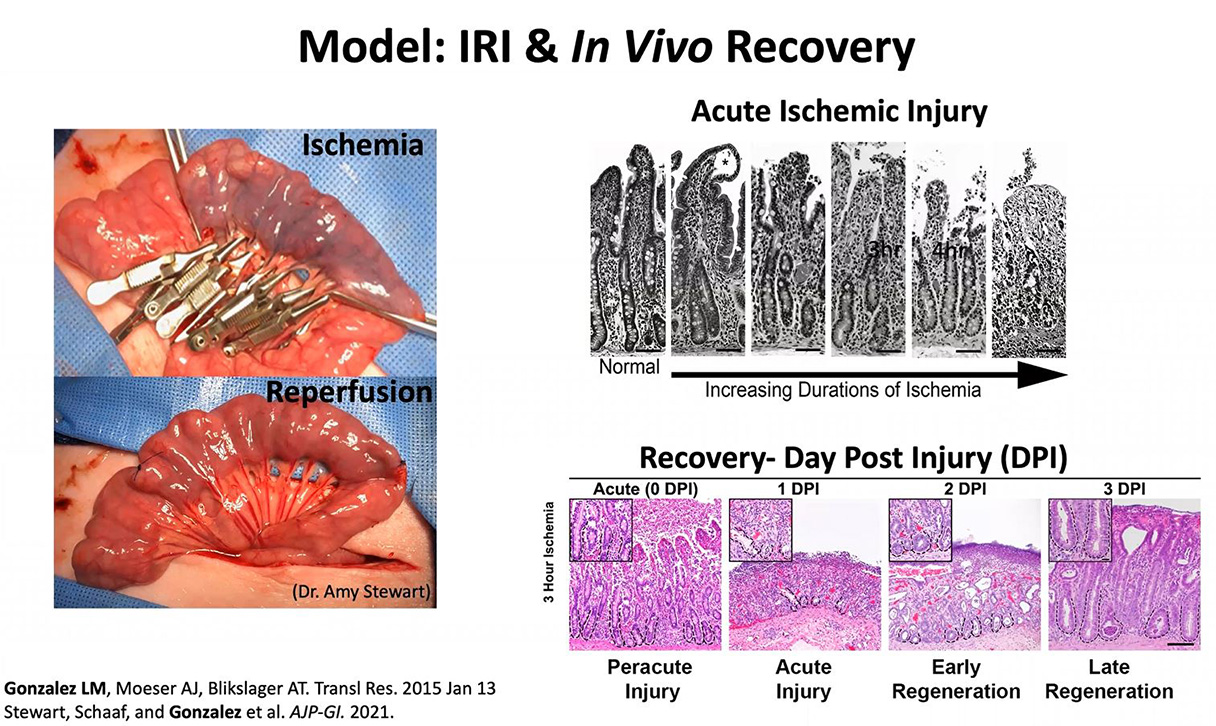

Gonzalez and her colleagues can induce intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury in pigs by clamping off the blood supply to the intestine. Some blood innately flows back to the intestine, but the process still causes injury. There are two ways researchers can observe the effect of the disruption of blood. First, they can watch in vivo, by placing the pig intestine back into the model and seeing the progression of recovery. A second observation can be done in vitro, by examining samples of tissue that are cultured and undergo a complete gene-expression analysis. In the injured intestine, Gonzalez and her team can see the epithelium lining is slowly fading away (see image below), but despite severe injury, the intestine begins recovery within three days. Indeed, in humans, stem cells turn over every 24 hours and a new intestinal lining grows every seven days.

Gonzalez’s research aims to reduce the impact of digestive disease by developing a viable model to understand its development and progression. In the United States, approximately 236,000 human deaths each year are the result of digestive disease. Of those deaths, approximately 14,400 are attributed to vascular disorders of the intestine, or intestinal ischemia. Gonzalez and her team are working with clinicians at Duke University to find a successful strategy for intestinal transplantation with an increased survival rate. Elisa Ludwig, a PhD candidate working with Gonzalez, found that a process known as NMP, for Normothermic Machine Perfusion, results in less injury compared to standard cold storage of tissue for grafts, and has led to success using tissue regeneration in pigs. With the NMP, Gonzalez states that they “basically keep the intestine as if it were almost a person. We have multiple pumps, we’re checking glucose and calcium, we’re doing full blood parameters and evaluating this intestine as if it were living, then transplanting it.” Gonzalez has full animal intestinal transplants scheduled for the near future.

Intestinal ischemia and reperfusion injury can be life-threatening, but they are preventable. Gonzalez believes that NMP could make organ transplants more equitable. Even in the United States, she says, transplants are “less commonly accessible to underserved communities because there are less people to match with.” NMP could increase that pool, she says, “if we can more effectively store the organs.” With more research, intestinal stem cells and NMP could become a reliable option for organ repair.

Tweets highlighting the talk follow below.

This blog was produced in collaboration with Science Communicators of North Carolina.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.