Drains on the Heart

By Robert Frederick

Young women have a low risk of heart disease, and sex differences in this bodily system could help explain why.

Young women have a low risk of heart disease, and sex differences in this bodily system could help explain why.

There’s a second vascular system on the surface of our hearts. It doesn’t carry blood. Instead, its function is to drain away interstitial fluid—the fluid in between our cells, made from the stuff that leaks out of our capillaries—and transport it back into the circulatory system. These drains on the heart are part of the lymphatic system. A dysfunctional system leads to edema, or swelling, which could reduce cardiac function or result in poorer healing after a heart attack.

Trincot et al.

“The surprise was finding that just the state of being female means that there are more lymphatic vessels in a normal heart,” says vascular biologist Kathleen Caron. “We didn’t expect that the anatomy between males and females would be so different.”

Differences between male and female hearts, including the ways they react to treatments (such as the preventive effects of low-dose aspirin) have been shown through decades of research and clinical trials. But it wasn’t until 2014 that the U.S. National Institutes of Health created policies to ensure that earlier, preclinical research in cells and animals addressed sex-based differences.

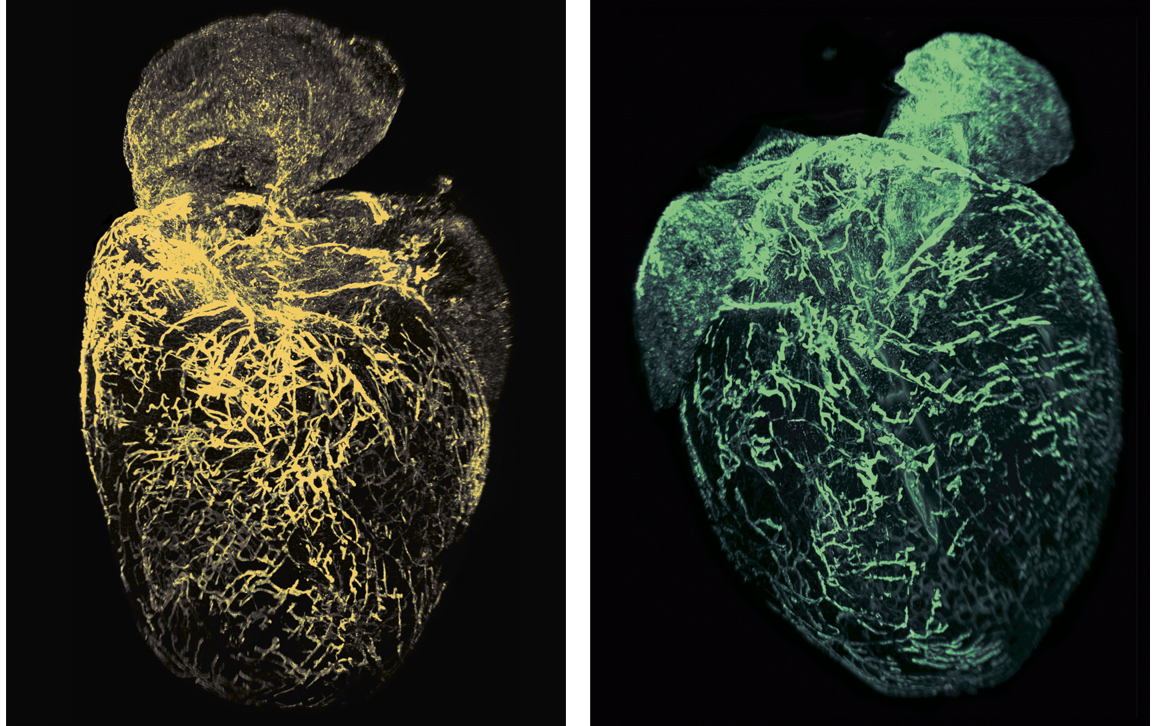

Coincidentally, that was around the time that, in Caron’s lab at the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, graduate student Claire Trincot started investigating the response of the lymphatic system to a heart attack. Recent advances in tools to study vascular biology meant it was possible to see the heart’s lymphatic system—still in place surrounding the heart—without imaging the underlying heart tissue. So Trincot sought to establish a visual baseline by imaging the healthy, uninjured cardiac lymphatic system of male and female mice. The university had just acquired the last of the necessary tools to do so, namely, light-sheet microscopy, which can capture high-resolution images throughout the entire heart (pictured below; 3D version above). “I think we were the first team here to use it,” says Trincot.

Adapted by Barbara Aulicino from Trincot et al.

That imaging also required modifying an established protocol (called iDISCO, for Immunolabeling-enabled three-Dimensional Imaging of Solvent-Cleared Organs) to make the dense tissue of the heart translucent and tag just the heart’s lymphatic system with antibodies that would fluoresce under laser light. “The heart is a very, very dense tissue,” says Trincot, “and so to permeate these solvents deeper than the surface is difficult.” After a bit of trial and error, Trincot’s modifications to the iDISCO protocol worked. “I haven’t optimized it” to shorten some of the steps and still get a good image, says Trincot, “but because it worked we just stuck with what we had.”

After the surprise that healthy female mouse hearts had more lymphatics than their male counterparts, Trincot, Caron, and their colleagues then tested whether the peptide adrenomedullin— already known to be expressed in lymphatic vessels—contributes to the growth of new lymphatic vessels. It did, in both male and female mouse hearts. And after inducing heart attacks in the mice, the team found that growth helped regulate cardiac edema. The researchers reported their findings in the January 4 issue of Circulation Research.

“Could it be that female mice have more lymphatic vessels because they have more of this adrenomedullin peptide?” asks Caron. “That’s a possibility, and it’s one we haven’t formally tested yet.” She adds, however, that “the adrenomedullin peptide is actually regulated by the estrogen hormone.” So a question that’s far more interesting to Caron is whether one reason younger women are protected from heart disease is because they just naturally have more of these beneficial lymphatic vessels within their hearts. “Postmenopause,” when estrogen levels go down, Caron says at this point, “I don’t have an answer for you.”

In a small pilot study, researchers in Japan infused adrenomedullin into the bloodstreams of patients shortly after they had heart attacks. “The outcomes were fantastic,” says Caron, and showed improved heart function and short-term survival. But she says it would be better to target the pathways activated by adrenomedullin instead of using adrenomedullin itself. That’s because not only is adrenomedullin expensive to produce, it doesn’t last very long in the bloodstream and it dilates blood vessels, so it could easily lower blood pressure to dangerous levels.

There are a lot of different directions along this research path, including further investigations into ways to boost the therapeutic potential of adrenomedullin that’s naturally produced by the body after a heart attack. Caron also plans to continue to develop additional animal models for studying myocardial edema, as well as male and female differences. Many other directions are possible, too, says Caron: “We talk about it at every lab meeting.”

A podcast based on a visit to Caron's lab:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.