This Article From Issue

January-February 2016

Volume 104, Number 1

Page 11

DOI: 10.1511/2016.118.11

In this roundup, digital features editor Katie L. Burke summarizes notable recent developments in scientific research, selected from reports compiled in the free electronic newsletter Sigma Xi SmartBrief. Online: https://www.smartbrief.com/sigmaxi/index.jsp

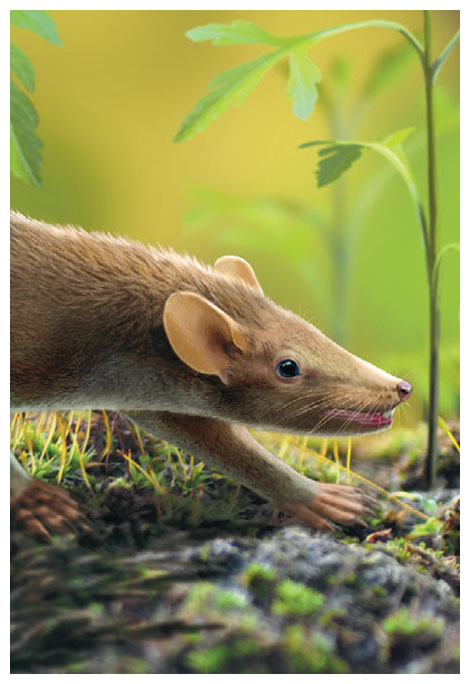

Best Early Mammal Fossil Found

A remarkably intact fossil of a 125-million-year-old mammal provides the earliest record of hair structures and inner organs. Through a rare mode of fossilization, the chipmunk-sized animal, named Spinolestes xenarthrosus, was found with guard hairs, underfur, hedgehog-like spines, and even evidence of a fungal skin infection. Soft tissues that were preserved included those of the earlobe, liver, lung, diaphragm, and skin. Found in Spain, S. xenarthrosus ran in a lush and diverse wetland of the Cretaceous period and belongs to an extinct mammalian branch, the triconodonts. The finding reveals that the hair and skin structures of modern mammals were present even in such early members of this lineage.

Oscar Sanisidro

Martin, T., et al. A Cretaceous eutriconodont and integument evolution in early mammals. Nature 526:380–384 (October 15)

Mars Water Lost and Then Found

A recent study reveals how Mars lost much of its early water, while another indicates that some liquid water still remains. Data from NASA’s MAVEN orbiter show that solar storms stripped away most of Mars’s once-thick atmosphere. Particles from the Sun collided with molecules in the atmosphere, knocking them into space or giving them an electric charge that caused them to be swept away by the solar wind. As the air was lost, so was the water that made up ancient lakes and perhaps an ocean. Most of the planet’s remaining water is now frozen or buried, but clues over the past decade suggested that some liquid water, a presumed necessity for life, might survive in underground aquifers. This theory was confirmed when spectral studies from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter identified hydrated salts in transient dark streaks along Martian slopes. More research is needed to determine the source of this water, however.

Jakosky, B. M., et al. MAVEN observations of the response of Mars to an interplanetary coronal mass ejection. Science doi:10.1126/science.aad0210 (November 6) Ojha, L., et al. Spectral evidence for hydrated salts in recurring slope lineae on Mars. Nature Geoscience 8:829–832 (September 28)

Portion of Rat Brain Simulated

Researchers from the controversial Blue Brain Project reported that they have built a supercomputer-modeled reconstruction of the microcircuitry in a sand-grain–sized section of rat brain. The project, which aims to eventually simulate the entire rat brain, has been criticized for its feasibility and high budget. The researchers consider this draft, which simulates the workings of 31,000 brain cells with more than 37 million synapses, a first step but not a proof of principle. Brain cells in the model were classified by morphology, electrical behavior, and the type of synapse—connections between cells that transmit signals. Certain simulated brain activities were shown to act like that of living rat neural tissue. The data for the simulation are available for other scientists to check and use.

Markram, H., et al. Reconstruction and simulation of neocortical microcircuitry. Cell 163:456–492 (October 8)

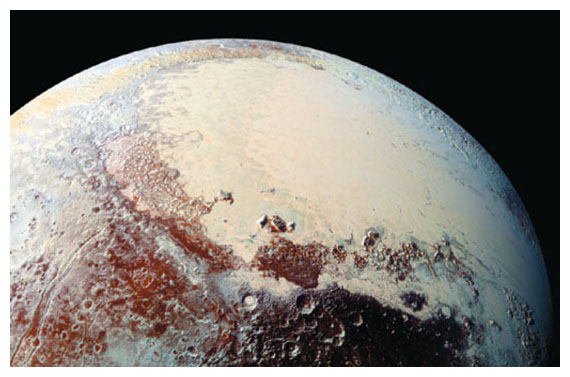

Pluto, Unveiled

A study summarizing the major findings of the New Horizon mission’s Pluto flyby raises questions about the dwarf planet’s geology, atmosphere, and formation, as well as those of its moons. Preliminary results from the probe reveal that Pluto has icy mountains and is geologically active, perhaps due to the decay of radioactive elements deep inside the planetary body. Parts of Pluto’s surface are unexpectedly smooth, suggesting that resurfacing covered up any craters once there. This finding raises the possibility that other dwarf planets in the Kuiper Belt could also have surprising tectonic and volcanic features. Pluto’s big moon, Charon, also showed puzzling signs of geological activity. Other geological features of Pluto and Charon suggest that one or both of them were not fully formed when they collided long ago. Further study could reveal roughly when and how this collision occurred. Researchers were also surprised by the complex structure of Pluto’s thin atmosphere, which contains multiple distinct layers of haze. The results change much of what was thought about the bodies in our solar system beyond Neptune.

NASA/New Horizons Image Gallery

Stern, S. A., et al. The Pluto system: Initial results from its exploration by New Horizons. Science doi:10.1126/science.aad1815 (October 16)

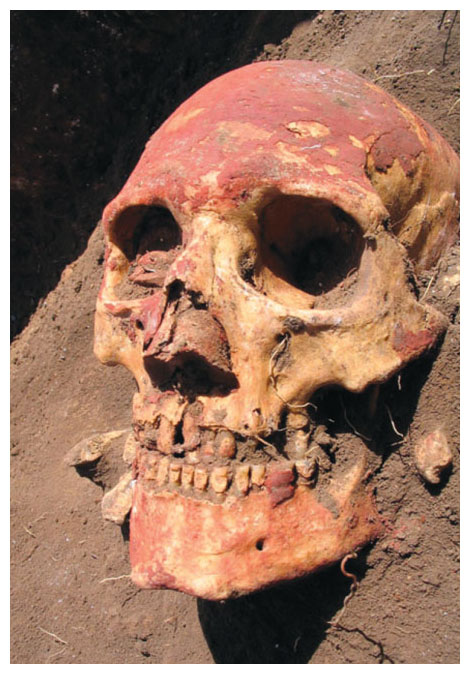

Earliest Plague Victims Found

DNA from Bronze Age human skeletons indicate that the black plague could have emerged as early as 3,000 BCE, long before the epidemic that swept through Europe in the mid-1300s. The study suggests that the disease did not spread with such intensity, but that it may have driven human migrations across Europe and Asia. In the analysis of fragments of DNA from 101 Bronze Age skeletons for sequences from Yersinia pestis, the bacterium that causes the disease, seven tested positive. The oldest sample came from an individual who lived in southeast Russia about 5,000 years ago. Two of the samples also contained enough Y. pestis DNA to reconstruct its genome. These strains of plague shared most of the genes associated with the virulence of the Black Death. They lacked a gene that helps the bacterium colonize fleas, however, an important vector for the Black Death, indicating that these Bronze Age strains were not as transmissible. The ages of the skeletons correspond to a time of mass exodus from today’s Russia and Ukraine into western Europe and central Asia, suggesting that a pandemic could have driven these migrations.

Rasmussen et al./Cell 2015

Rasmussen, S., et al. Early divergent strains of Yersinia pestis in Eurasia 5,000 years ago. Cell 163:571–582 (October 22)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.