This Article From Issue

May-June 2003

Volume 91, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2003.44.0

Alchemy Tried in the Fire: Starkey, Boyle, and the Fate of Helmontian Chymistry. William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe. xvi + 344 pages. The University of Chicago Press, 2002. $40.

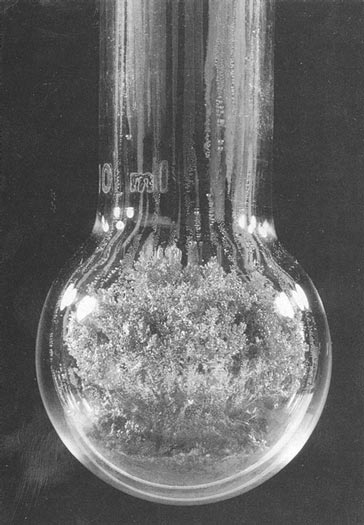

Open a window on an alchemical laboratory, and what do you expect to see? The kind of typical dark, messy, enigmatic room that Dutch paintings have fixed in our memory. But in Alchemy Tried in the Fire, William R. Newman and Lawrence M. Principe offer a visit to a 17th-century alchemical laboratory that will surprise you.

Alchemy has long been presented as the opposite of modern chemistry, which is alleged to have been founded by Robert Boyle. Alchemy is described as a set of empiric and artisanal practices deprived of theoretical roots, or as a sterile pursuit of the philosophers' stone caught up in vain speculations; it is characterized as lacking the intellectual discipline of chemistry. Although it is conceded that modern chemists have inherited bits and pieces of laboratory equipment and recipes from the alchemists, the notion that the two disciplines are discontinuous has prevailed. This view was encouraged by the rhetoric of chemists in the 17th and 18th centuries, who wanted to distance themselves from alchemy.

From Alchemy Tried in the Fire

For about 10 years, Newman and Principe have been challenging this received wisdom, in both separate and joint publications. Their common focus is early modern "chymistry," a term used precisely to bridge the alleged gap between alchemy and chemistry. In this book they join efforts to exploit a rich gold mine: the laboratory notebooks kept in the 1650s by George Starkey, an American chymist who signed his works Eirenaeus Philalethes. The manuscript of the notebooks, with annotated translations from Latin into English, will soon be published as a companion volume to Alchemy Tried in the Fire. Starkey's notes reveal a surprisingly familiar method of research: Starting from the existing literature, he made conjectures and then carried out experiments and drew conclusions. The notebooks are plain and clear, whereas Starkey's publications concealed the whole procedure by employing allegorical conceits and syncope (the omission of some steps and ingredients). Even when Starkey mentions that God has revealed something to him, he submits the divine inspiration to laboratory tests, which do not always confirm God's brilliant idea. Moreover, Starkey's descriptions of divine revelations strangely resemble the flashes of inspiration, dreams or visions that are common in more modern narratives of scientific discovery.

To emphasize Starkey's historical importance, the authors provide detailed accounts of the experimental practices of two more famous figures: his master, the Belgian Joan Baptista Van Helmont, and his pupil, Robert Boyle. Van Helmont maintained that weight is always conserved, an idea too often credited to Antoine Laurent Lavoisier. The authors suggest that Lavoisier took what came to be called his "balance sheet" technique (an element-by-element weighing of the initial ingredients and final products in a chemical reaction to demonstrate the conservation of mass) from Wilhelm Homberg, a chemist at the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris in the late 17th and early 18th centuries who heavily influenced following generations. And Homberg adopted this approach from Starkey, who had himself borrowed it from Van Helmont.

That Boyle is Starkey's heir is even more obvious. Starkey tutored Boyle's early steps in natural philosophy. In 1650 Starkey immigrated to London and there introduced his experimental methodology, and Van Helmont's theories, to Boyle. The interaction between Starkey and Boyle survived Starkey's bankruptcy and imprisonment for two years in the mid-1650s and may have continued until his premature death in the great plague of 1665. However, Boyle rarely acknowledged his debt to Starkey. Not only did he not explicitly quote Starkey, but more than once he presented Starkey's results as his own discoveries. The modern view of the Hartlib circle (to which Boyle belonged) as a community of friendly cooperation and free communication thus needs to be replaced by a more realistic appraisal of the group as consisting of rival scientists claiming priority and pushing themselves to the front of the stage.

At the core of Alchemy Tried in the Fire is a detailed picture of 17th-century chymical laboratory practice. Newman and Principe manage within the constraints of a scholarly publication to write in a clear and easy style accessible to all.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.