Ars Scientifica

By Anna Lena Phillips

An art-science collaboration yields rich insights.

An art-science collaboration yields rich insights.

DOI: 10.1511/2008.71.205

Joint efforts between historically distinct disciplines raise a lot of questions—and, sometimes, eyebrows. In the case of art-science collaborations, skepticism can threaten to jettison experimentation: What can art say that science hasn't already said?

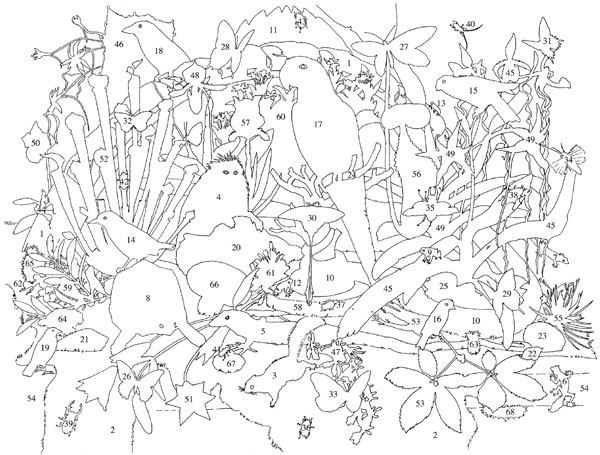

An exhibit at the U.S. National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., suggests some answers to this question. Taxa, a series of paintings by Isabella Kirkland, groups species together in innovative ways that can stimulate conversation about human impact on the environment.

Isabella Kirkland/Feature Inc., N.Y.

A visual artist and a research associate in aquatic biology at the California Academy of Sciences, Kirkland had already cultivated knowledge of and respect for the science of taxonomy when she began the series. "I had been working on individual, local endangered species," she says. "As the millennium was coming to an end, I decided to work on a grand scale—something more like a time capsule." The result of this exploration was the first painting, "Descendant" (1999), which portrays 61 species listed as endangered (or, in some cases, "presumed extinct") in the mainland United States, Hawaii or Central America.

Five subsequent paintings point up other issues in conservation science and biodiversity. "Ascendant" (2000) portrays species that have been introduced to the United States and are thriving.

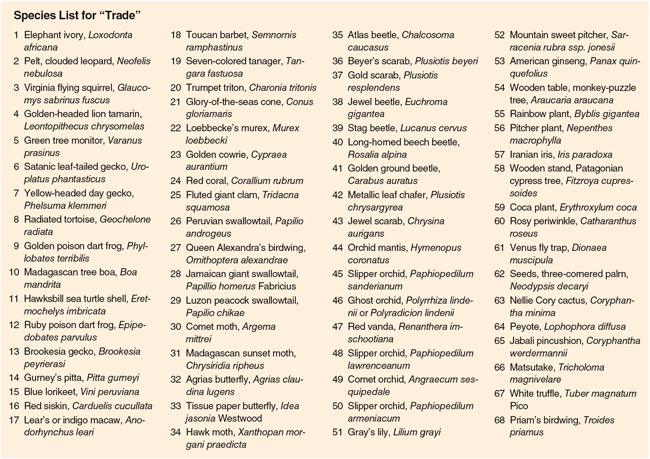

"Trade" (2001, shown here) includes species that people value, harvest and sell, and whose populations have thus been depleted. The work's vivid colors underscore the human desire to own these creatures. "Gone" (2004) catalogues full-species, worldwide extinctions. Its colors are more subdued, making the piece a memorial to the organisms shown. Kirkland is currently working on Nova, three new paintings that depict species discovered since the passage of the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 1973.

Planning compositions that portray such great numbers of species with anatomical accuracy is a challenge, so Kirkland decided at the outset to use a time-tested genre. "The Dutch masters' still lifes looked pretty good after 400 years—you can pick out the genera of the bugs," she says. The paintings in Taxa use the genre to great effect. The large canvases are packed with life, but each animal and plant is rendered distinctly.

The series is the product of painstaking research. "I begin with the data," Kirkland says. She reads current scientific literature to find new leads, collecting detailed information on particular species. When she decides to include a species, she tries to see a specimen of it so that she can draw it at life size. "People are very generous with their time," she says. "Every time I go into any museum, I'm so profoundly shaken by the number of man-hours it represents. That's part of what I'm trying to laud."

Kirkland is modest about her hopes for this integration of biology and art. "If I inspire even three people to become taxonomists, I've won," she says. "They're not training taxonomists anymore—it doesn't have the bling of genetics." But considering species' differences and similarities is essential for our knowledge of how the world works, she believes. She also hopes the paintings will inspire people to "pay attention to biodiversity and think about their actions in terms of it." And the medium of painting itself has advantages: It can "get people to slow down" and have a deep experience of the art.

Isabella Kirkland

The work offers insights for visual art as well. "Nature art has sort of a bad name in the 'real' art world," says Kirkland. "I wanted to change that, to depict wildlife in a way that's not naïve." But the paintings do not sacrifice artistry for accuracy. The lush, well-balanced compositions invite the viewer's eye to travel around the canvas.

"The species in each painting don't belong together—so it's a fantasy in that regard," she says. Perhaps paradoxically, by removing species from their habitats, the paintings acquire the power to change our perception of the plants and animals within them. In this sense, Kirkland's work moves beyond the representation of scientific ideas to offer new ways of thinking about the organisms she depicts.

To broaden the audience for these works, Kirkland maintains a Web site, isabellakirkland.com. Users can explore the paintings and read more about select species. The Nova series will be added to the site once it is complete. She is also producing a series of three-quarter-size prints of the paintings. But the best way to experience these works will be to see them live and up close. The free exhibit, in the upstairs gallery of the National Academy of Sciences, runs April 10 to August 25 of this year.

A basic test for art-science might be whether it succeeds when judged by the standards of each discipline. The Roman poet Horace's dictum—"teach and delight"—comes to mind. Or, to use more-modern terms, is the project accurate and useful? And is it pleasing—does it succeed aesthetically? It will be revealing to consider other art-science collaborations in a similar light. As for Kirkland's paintings, it seems safe to answer both questions with a resounding yes.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.