Treating the Side Effects

By Fenella Saunders

Cancer immunotherapy can cause cognitive decline, and immune cells in the nervous system might be the culprits.

Cancer immunotherapy can cause cognitive decline, and immune cells in the nervous system might be the culprits.

Treatments that enhance the defenses the body already has in place have greatly advanced the fight against cancer. Such a boost is the mechanism underlying an established therapy used for solid cancers, such as melanomas and small-cell lung cancers, and trials are underway for other cancer types. The treatment blocks a protein on immune cells that can lead to cell death, which keeps the immune system in a hyperalert state that makes it better at destroying cancer cells. However, oncologists such as Robert Zeiser at the University of Freiburg in Germany began to see that some patients on this type of cancer immunotherapy experienced neurological side effects such as memory loss, which in a few cases were serious enough to lead to encephalitis or coma. In a recent study in Science Translational Medicine, Zeiser and his postdoctoral researcher Janaki Manoja Vinnakota, along with their colleagues, untangled the reasons why these side effects occur.

The protein targeted by this cancer immunotherapy is called PD-1, short for programmed cell death protein-1. The therapy uses an antibody to block this protein’s receptor on T cells. Cancer cells produce markers that turn off immune cells and fool them into seeing the cancer as normal cells. The therapy keeps immune cells active so they don’t recognize these repressive markers and will kill the cancer cells. But keeping the immune system in this hyperactivated state can have negative consequences, because another type of immune cell that resides in the nervous system, called microglia, also have the same receptor. These cells have close interactions with neurons, and help control many brain activities. “Once microglia are active, they also meddle with the normal cognitive processes, which might cause neurotoxicity,” Vinnakota explains.

J. M. Vinnakota, et al., 2024, Science Translational Medicine 16:eadj9672 (all 4 images)

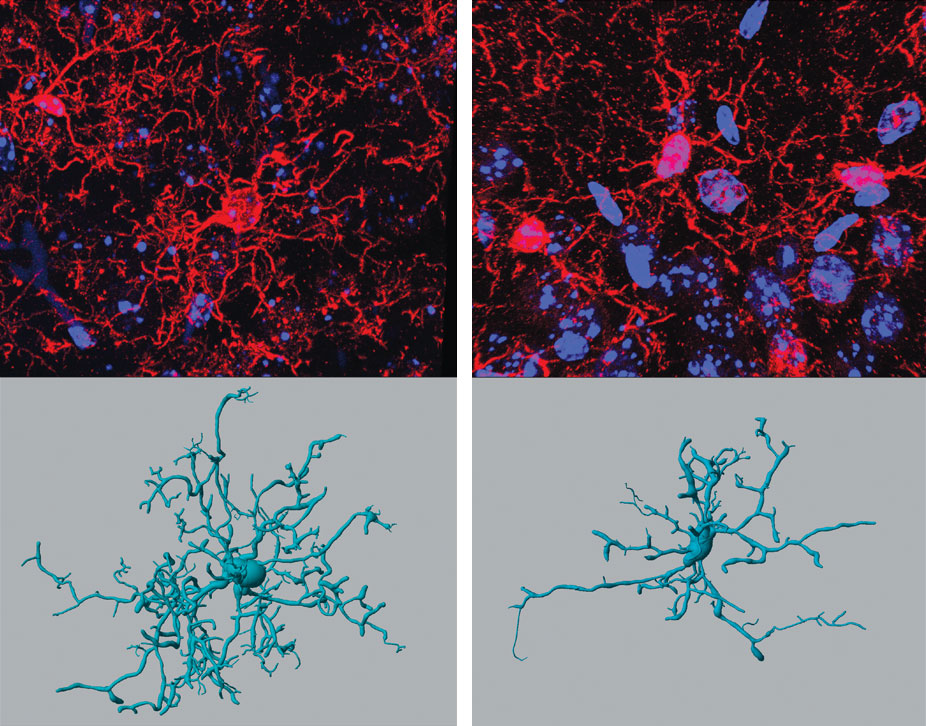

To see if microglia could be behind the neurological side effects, the team first treated a cell culture of microglia with two different clinically approved anti-PD-1 antibodies. They found an increased level of a marker associated with microglia activity. They next treated healthy mice with the anti-PD-1 therapy. Tissue samples from these mice likewise showed that microglia were activated after the therapy. “Microglia, under normal conditions, are highly branched; they tend to look around for any potential threat,” Vinnakota explains. “If there is one, they retract their processes and attain an amoeboid phenotype.” When the team then tested mice that had a knocked-out immune system, they didn’t see as much activity.

One curiosity the researchers had about their findings was that the blood–brain barrier should keep the anti-PD-1 therapy out of the nervous system. But Vinnakota and her colleagues found that the therapy actually causes inflammatory damage to the barrier that allows it to pass through.

The team next treated mice with tumors and found that they showed cognitive deficits similar to those seen in human patients. The mice did not favor new objects over ones that they had already been extensively exposed to, indicating that they did not have memory of objects that should have been familiar.

The markers produced when the microglia are activated seem to cause the cognitive damage. These markers include a type of enzyme called a tyrosine kinase that acts as a sort of protein switch—in this case, one called Syk. Kinases are important for the function of the immune system, but they also promote inflammation. “Increased levels of Syk activation are somehow damaging the neurons in the vicinity, which is why we see cognitive deficits in the treated mice,” Vinnakota said.

The good news, however, is that there are already commercially available inhibitors that work on Syk. When the team treated the cognitively impaired mice with these inhibitors, they were able to reverse the decline.

Although the studies so far have been limited to mice, Vinnakota thinks that, following further research, there could one day be the option of blocking Syk in patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy who start to show indications of cognitive decline. “The people who get cognitive decline are suffering a lot, so they have to stop this anti-PD-1 therapy, and that increases the relapse of the tumor, and then they have to look for some other treatment options,” she says. “It’s really bad for the ones who are suffering.”

Optimally, Vinnakota hopes, researchers will develop early-diagnostic tools that can spot patients who are likely to have side effects from anti-PD-1 therapy, so they can be preemptively treated with blockers for Syk. “That would be really helpful to treat them better,” she says, “so that we can still have the anti-PD-1 therapy ongoing, because it is an effective therapy for many of the patients.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.