Unscrambling the Signal of Higher Vaccine Exemptions

By Brian G. Southwell, Mary Klotman, Reed V. Tuckson

Overcoming opt-outs will require strengthening ties and trust between patients and the health sector.

June 24, 2024

Macroscope Medicine Immunology

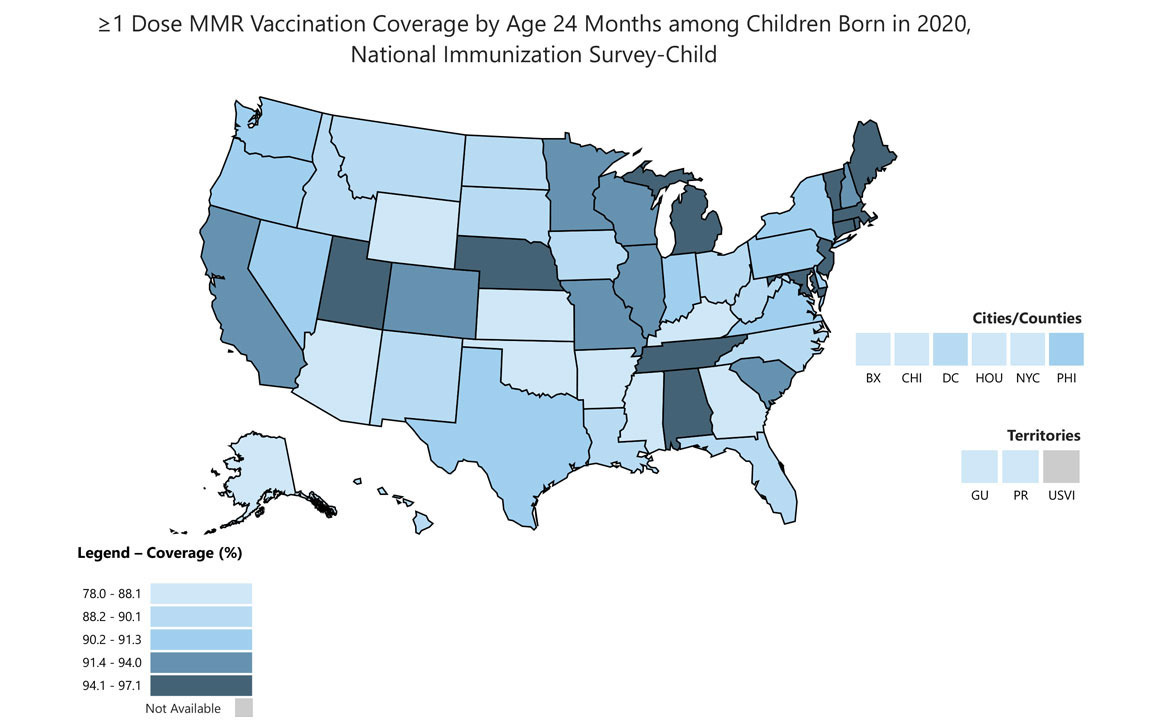

In November 2023, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the proportion of families opting out of routine childhood vaccinations was larger than ever previously recorded, a story that is part of a larger pattern of recent concerns about vaccination hesitancy and refusal. That pattern is not limited to families with children. As of March, the CDC noted that older Americans are not fully vaccinated against influenza, COVID and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Among people age 60 and older, only roughly a quarter have received an RSV vaccine. Although reasons for skipping vaccinations may vary, the consequences generally will be the same: Across the United States, families will lack protection against preventable infectious diseases, which could spread more rapidly and more widely than before. What exactly this pattern suggests about the relationships between families and our health care and public health systems warrants close examination.

CDC.

One worry expressed by researchers, government officials, and others is that inaccurate information—whether encountered on social media platforms, shared among friends, or discussed around the family dinner table—may discourage people from following recommendations from health professionals. Countering the effects of false information about health and medicine or even clearly delineating what those effects are is challenging; it is certainly made more so by the ease with which misleading information can be shared with the click of a button. Further, the way misinformation affects people’s judgments and decision-making can be subtle; we should not always expect an easily identified, straightforward relationship between exposure to some single piece of misinformation and a corresponding decision or action.

Some news stories have suggested that we are experiencing a novel wave of hostility toward, and rejection of, health-related expertise, but the true story is likely more complex. People do not receive recommended care for many reasons. Misinformation on health topics such as vaccination also is not a new phenomenon. In short, the proliferation of medical myths in United States and global information environments is more likely a symptom of larger problems, not the cause.

We should not always expect an easily identified, straightforward relationship between exposure to some single piece of misinformation and a corresponding decision or action.

Lost Connections

When we ask why some people seem not to follow through on medical advice to get vaccinated (or to follow other health recommendations) it is important to remember that many individuals and families do not have a family or personal physician or a consistent personal relationship with a known and trusted care provider. For many people, getting a vaccination or accessing care in general amid a constantly shifting health care landscape may mean navigating an array of retail stores or outpatient clinics while trying to balance busy work schedules, transportation challenges, and childcare obligations. Juggling everyday obstacles to wellbeing while not having a consistent source of medical consultation and advice can undermine a patient’s sense of safety and assurance. Part of the story, then, is the fractured state of health care delivery in this country.

A Lack of Trust

The story also hinges on public trust in science and health care. People sometimes receive conflicting advice or inaccurate information from health care providers, and yet we also know that the degree of trust or confidence a person has in scientists and health care professionals at least partly reflects working knowledge of how those professionals do their work. One telling example appears in the 2024 edition of Science and Engineering Indicators (a biennial report to Congress on the state of science, engineering, technology, and mathematics), which examined factors related to public confidence in research, among other topics. According to evidence in that report, a person was more likely to express a high degree of confidence that medical researchers will attempt to act in the best interests of the public if that person understands that science is a process that involves testing ideas over time to produce accurate conclusions. Research on trust in federal, state, and local government agencies similarly suggests the importance of transparency and information clarity in encouraging perceptions of institutional trustworthiness; knowing how institutions function sometimes can encourage a greater sense of shared values between institutions and the communities they serve.

Potential Solutions

In November 2023, the nonprofit research institute RTI International and Duke University, in conjunction with the new Coalition for Trust in Health & Science, hosted the National Forum on Best Practices to Address Health Misinformation in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, to explore what health care organizations can do to mitigate the influence of false or misleading information on patients. The meeting featured a series of presentations by scholars and clinicians who have been exploring strategies aimed at countering misinformation encountered by patients outside of the clinical setting.

During the two-day summit, one important insight that emerged was that patients’ acceptance of inaccurate information is at least partly a symptom of a failure by our health care and public health systems to communicate clearly and effectively. To encourage greater trust in medical research, health care providers and allied professions cannot simply blame the influence of any single myth or false claim spread online or in electronic media. Instead, they must ask why individuals and families are making certain decisions and be prepared to listen to the answers they receive. One path forward would be to further invest in projects that work toward greater transparency in communicating with patients and the public about medical care and the implications of findings from medical research. At a minimum, this requires a commitment to offer clear, accessible explanations about how scientists conduct and report research, as well as to candidly discuss the strengths and limitations of scientific research. Mentioning research limitations alone and stating that we “just cannot be sure about anything” is not a solution, as that could encourage third parties to unduly focus on those limitations. Rather, noting what we have learned through research as well as what we do not yet know can offer a helpful picture to a patient. Simply urging a person to do something is often not nearly as effective as explaining the rationale behind the request in a way that respects that person’s ability to understand it.

Ultimately, the reasons behind the concerning recent increase in rates of vaccine exemptions in the United States are multifaceted. Attempting to counter false or misleading claims that permeate social media might be worthwhile if done according to evidence-based best practices (such as having credible sources issue corrections and clearly articulate factual errors rather than shaming audiences for having accepted an idea), but such effort online will not by itself ensure that families have access to convenient, affordable care and the opportunity to have meaningful interactions with clinicians. Nor will such an approach necessarily equip parents with all the answers they seek as they weigh decisions that will affect the health and well-being of their children. Within health care organizations, however, we can take steps to build a workforce better equipped to help families navigate the challenges of the medical information environment and make informed decisions about care.

Medical Training Implications

Our health care organizations and public health agencies must build collaborative organizational networks supported by evidence-based methods for effective communication and engagement. These networks should serve families’ information needs before they reach the examination room and after they leave it. We must also build formal capacity that enables health care providers to better listen to the concerns of families who would benefit from care, whether they interact with the health care system or not. That may mean finding ways to monitor community concerns outside of the examination room, which could mean partnering with community organizations. This goal has direct implications for medical training both prior to and following licensure. Introducing communication skill development into our biomedical and health professional training programs could help.

Collectively, the health care professions need to focus on building the kinds of communication competencies needed to mitigate the impacts of misinformation. One approach could involve formally recognizing competency-building in accreditation review. Fortunately, at least a handful of programs—such as teams at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in New York, Florida International University, the State University of New York at Buffalo, Maine Medical Center, Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, University of New England in Maine, the University of Chicago, and Duke University in North Carolina, among others—are beginning to integrate relevant educational elements in curricula, such as misinformation-related scenarios in training simulations, lectures for fourth-year capstone courses, and just-in-time conversation guides to act as refreshers for clinicians having patient interactions. The Association of American Medical Colleges has recently funded a promising set of misinformation mitigation projects at medical schools to generate training innovations that could be widely adopted across the country. Facilitating that adoption will require evaluating how we train. It will also entail the development of accessible toolkits that provide teaching materials and templates for organizational changes, such as the creation of personnel roles for community information environment monitoring.

Rising rates of vaccination exemption requests are a sign of trouble, but the main challenges we face are not due solely to the publication of conspiracy theories or outlandish social media posts. They stem from the frayed or absent relationships between families and health care organizations across the country that have affected family decisions. Seriously considering how we train medical professionals to navigate our information environment together with patients and their families could help to improve medical education and foster future patient adherence to recommendations in a way that short-term pronouncements about the state of that environment alone will not.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.