Conservation Across Borders

By Arturo Ramírez-Valdez

Research indicating that the giant sea bass is critically endangered did not consider data from Mexico, where the majority of the species lives.

Research indicating that the giant sea bass is critically endangered did not consider data from Mexico, where the majority of the species lives.

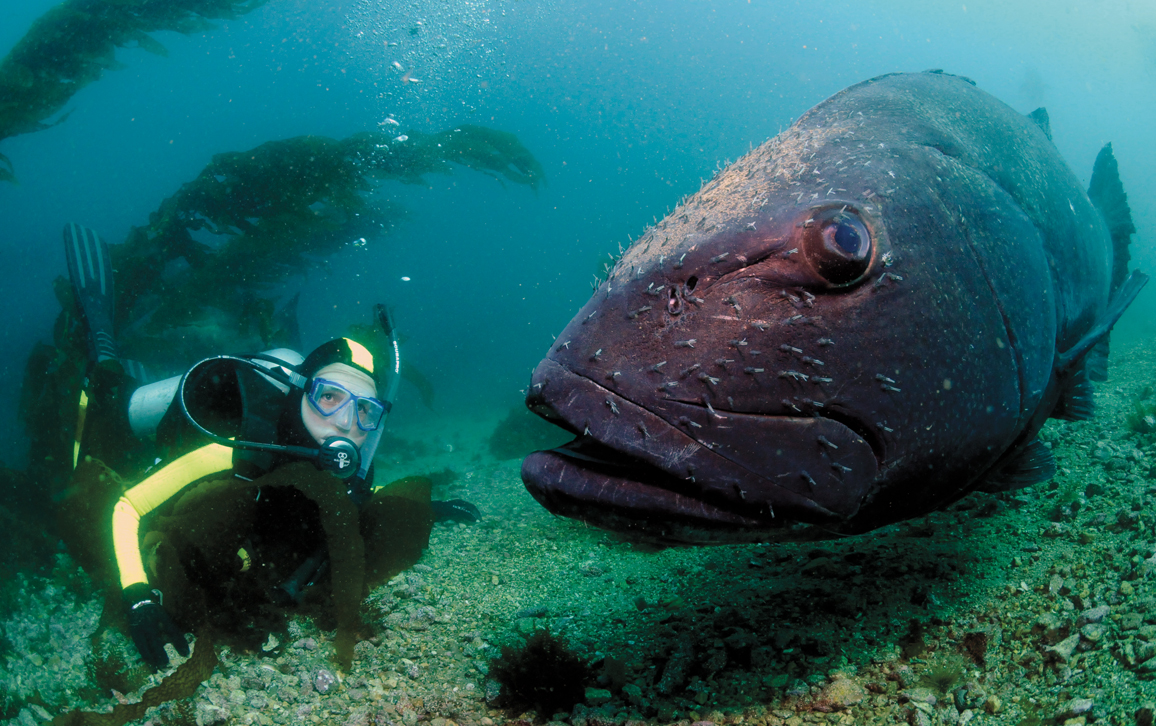

I was looking at the seafloor, focused on identifying fish species as I normally did when diving off the California coast, when I suddenly sensed something large above me. When I turned my head, I saw an enormous fish—more than 2 meters long—calmly investigating the air bubbling from my scuba regulator each time I exhaled. This 2016 dive marked my first encounter with a giant sea bass.

I am a marine ecologist who studies how international borders pose challenges for conservation and management efforts in aquatic environments. Despite the absence of walls or fences in the ocean, borders can still act as stark barriers for a variety of marine activities, including research.

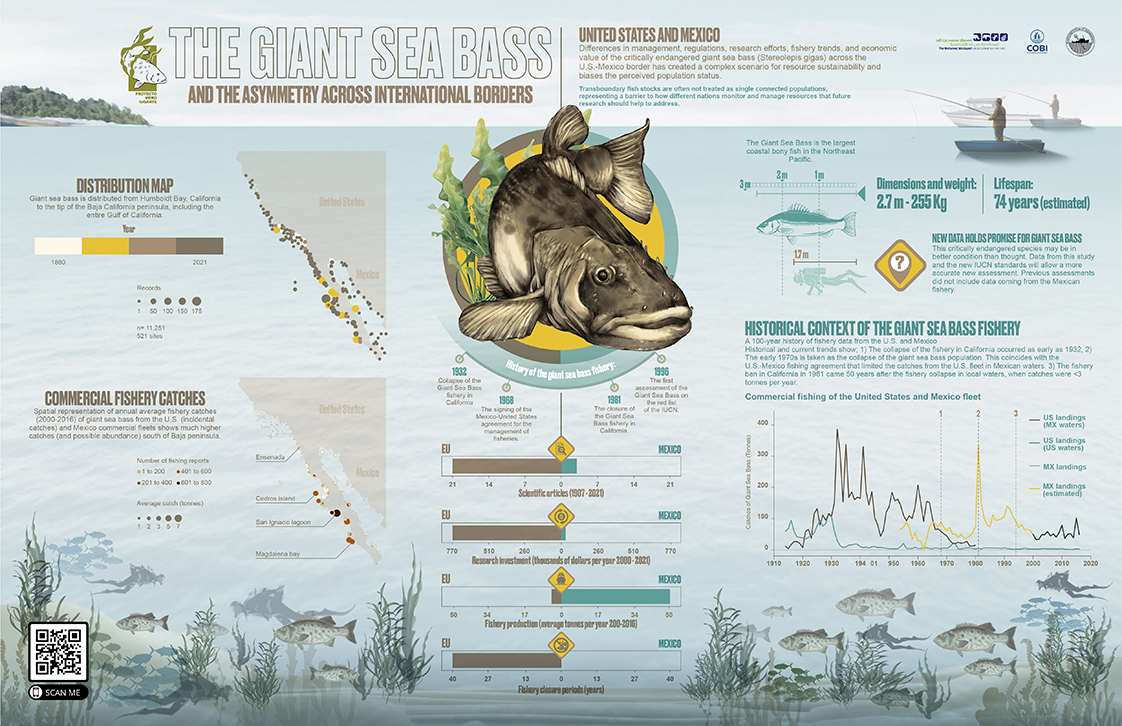

Giant sea bass live off the western coast of North America in both Mexican and U.S. waters. Large differences between the two countries in regulation and research efforts have led to a significant misunderstanding of giant sea bass population health, including the likely miscategorization of the species as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

The giant sea bass (Stereolepis gigas) is the largest coastal bony fish in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. It can grow to be up to 2.7 meters long and weigh up to 315 kilograms, and its life span can reach 76 years. It lives in coastal waters ranging from Humboldt Bay in far northern California to the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula in Mexico, including the entire Gulf of California. (In this article, I use California to refer to the U.S. state and Baja California to refer to the Mexican peninsula.)

Jeffrey Bozanic

In California, commercial fishing for giant sea bass began in the late 1880s. The fish were abundant across the entire range until the early 1970s, when a sudden reduction in yield led to the collapse of U.S. giant sea bass fisheries. In 1981 the United States banned both commercial and recreational fishing for giant sea bass, and in 1996 the fish was included on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as critically endangered due to the population being “severely fragmented, leading to a continuing decline of mature individuals.”

The giant sea bass population collapse in California and its subsequent protection along with a flurry of research on the fish in the United States stand in stark contrast to activities in Mexico, where few regulations govern fishing for giant sea bass, and there is almost a complete lack of data and research on the species.

The dearth of Mexico-based scholarship about giant sea bass is compounded by the problem that research from U.S. institutions stops at the border. My colleagues and I conducted an extensive literature review and found 56 unique, peer-reviewed articles that mention giant sea bass; of those, only three include any data or information from Mexico. The IUCN based its decision to categorize giant sea bass as critically endangered on a report that included no data whatsoever from Mexico. This lack of information about giant sea bass from Baja California and the Gulf of California is concerning, given that 73 percent of the species live in Mexican waters. This knowledge gap made me wonder whether ecologists had the wrong idea about the health of giant sea bass populations.

In 2017 I led an effort to document the giant sea bass population in Mexico and to look for clues that would indicate how their numbers may have changed over time. At the beginning of the project, my colleagues and I feared that the records in Mexico would confirm the precarious situation of the fish, as shown by data from the United States.

Despite the absence of walls or fences in the ocean, borders can still act as stark barriers for a variety of marine activities, including research.

To our surprise, from our very first assessments we found that giant sea bass were plentiful in Mexican fish markets and fishing grounds. The local fishmongers were never out of the fish; indeed when we inquired about their stock, they would ask, “How many kilos do you need?” It was clear that for fishers in Mexico, the species is still common in the sea and, therefore, in their nets. It is still possible to find big fish weighing as much as 200 kilograms, and the average catch weighs around 12 kilograms.

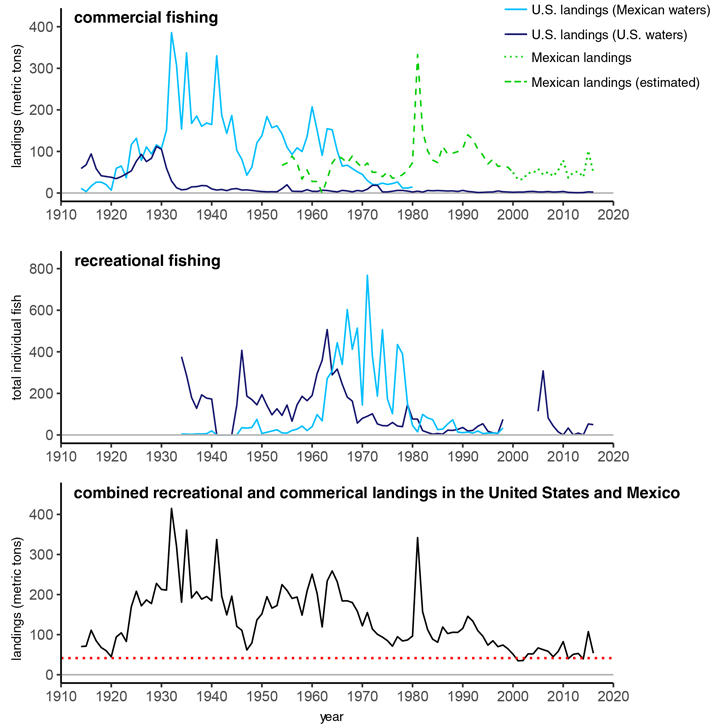

It was fantastic to see an abundance of these fish in markets, but I wanted to understand what led to the misconception of a dwindling giant sea bass population. To that end, I examined fishery trends through history and compared current fishing levels with those of previous years. Historical and contemporary fishing records show that the Mexican commercial fleet has caught an average of 55 tons of giant sea bass per year over the past 60 years, and catch size has been relatively stable over the past 20 years, with a peak in 2015 at 112 metric tons.

From Ramírez-Valdez, 2021

According to U.S. and Mexican records, the largest yearly catch on record for giant sea bass in Mexico was 386 metric tons in 1933. Biologists consider a fish population to have collapsed when total catches, under the same effort, are less than 10 percent of the largest catches on record. So a steady trend of 55 tons per year shows that in Mexico the species has not collapsed. It is clear that giant sea bass populations have faced severe declines throughout their range, but the health of the species is not as dire as previously thought.

We also found that the apparent collapse of California’s giant sea bass fishery documented in the 1970s actually began as early as 1932. As the U.S. commercial fleet overfished giant sea bass off the California coast over the first half of the 20th century, the boats moved into Mexican waters—but they continued to count all catches as being from the United States. This practice changed in 1968 when the two governments signed the Mexico–U.S. Fisheries Agreement, limiting how much fish each country’s fleet could take from the other country’s waters.

Thus the collapse of U.S. giant sea bass fisheries in the 1970s was not due to a drastic reduction in fish numbers in the region; it was driven by changes in fishing regulations between the United States and Mexico. California’s giant sea bass populations had been depressed for decades, but the lack of fish in the United States had been hidden by the continued supply from Mexico.

Based on my research, I believe that the giant sea bass may not qualify as a critically endangered species. My analysis of modern catch data suggests that the population of this iconic fish is likely much larger than biologists previously thought, especially in Mexico.

Over the 40 years since the California State Legislature banned commercial and recreational fishing of giant sea bass, the fish’s populations along the U.S. coast have begun to recover. In response, a new industry has emerged: scuba-diving excursions for tourists who want to swim with the massive fish in the wild. These types of experiences are currently far more common in the United States than in Mexico, but recreational scuba tours are beginning to take root south of the border as well. These businesses raise the nonconsumptive value of the giant sea bass, which could bolster efforts to reduce overfishing and to develop more sustainable fishery-management practices in Mexico.

From Ramírez-Valdez, 2021.

I am leading the next assessment for the IUCN; now that we have accumulated better data from south of the U.S.–Mexico border, we can make a more informed determination that balances responsible species management with human needs.

More accurate information about giant sea bass populations may become increasingly important as climate change continues to warm oceans. If the giant sea bass start migrating north and returning to the California coast in search of cooler waters, it will be crucial to have a sense of the total species population, both north and south of the U.S.–Mexico border. Otherwise, we will not know whether a growing number of giant sea bass in California is due to population explosion or dislocation.

I hope that our study inspires policy makers in the United States and Mexico to start a conversation about how to manage this incredible fish in a collaborative way. But I feel our work also has larger implications. It shows how asymmetry in research and data can create significant barriers to understanding the past and present status of a species such as the giant sea bass and make it harder to implement sustainable practices for the future.

This article expands on and is adapted from an article in The Conversation (www.theconversation.com).

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.