Data Collection During Social Distancing

By David Samuel Shiffman

The coronavirus pandemic has stopped this summer field research season—a disaster for some students. Here are some solutions to this growing problem in academia.

April 16, 2020

Macroscope Biology Communications

As university campuses shut down to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, many aspects of academics' personal and professional lives are being disrupted. It’s very likely that these campus closures and social distancing rules will result in the loss of some or all of the summer field research season, a critical research time when academics have few teaching responsibilities and can devote themselves to gathering data to be analyzed during the rest of the year.

Left image by Sonia Vedral; right image by Ashley Dayer.

For more senior academic researchers, this cancellation is disappointing—many love fieldwork, and the summer is the main time they get to do it. But for graduate students who may only get one or two field seasons to collect all the data they need for their thesis research, the loss of a summer field season can be a disaster, adding even more trouble to an incredibly stressful time. “In graduate school, students learn how to conduct their own science research,” says Ashley Dayer, an assistant professor in the Department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation at Virginia Tech. “In developing their skills as scientists, students design, collect, analyze, interpret, and present their own work. The lessons of collecting one’s own data are invaluable for going on to become a scientist, or working in a more applied career.”

If graduate students aren’t able to collect or analyze data, one of the main goals of graduate school isn’t achieved. “Especially in fisheries biology, there’s a strong component of professional training that goes beyond the required graduate-level coursework, including field techniques and data analysis,” said David Kerstetter, an associate professor in the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences at Nova Southeastern University. “Not having data means fewer publications, the currency of academia, which also affects future placement into doctoral programs. Not having field data collection experience would be a caution flag for any potential employee or prospective doctoral student in a position that would involve extensive fieldwork, even if that lack was due to something beyond everyone’s control.”

Although it may be impossible to collect new field data this summer, many scientists have tons of data from older projects that haven’t yet been analyzed, just sitting in a proverbial (or sometimes literal) drawer. If scientists with extra data could be put in touch with students who need data to analyze, it could solve a big part of this dilemma—and that is the goal of a sample-sharing platform called Otlet. “Many scientists have existing data sets, or ideas for quantitative reviews and meta-analyses, with the hope that one day we will get the time to work on them, but this very rarely occurs,” said Madeline Green, an Otlet cofounder and a scientist at the University of Tasmania’s Centre for Marine Socioecology. “Otlet has decided to help by 'matchmaking' students in need of research projects with researchers who have available data sets/ideas. We will attempt to match students' skill sets with the data sets and projects offered. We will then provide the contact details of those looking for data with those willing to share. Both the larger Otlet platform and this data-sharing service are helping scientists stuck during COVID-19. By up-cycling samples and data that already exist, we enable those who have lost field seasons and lab time to stay ahead and finish their projects."

Screenshot from Twitter feed

If there’s a match between what students are looking for and what’s available, the Otlet team will contact both parties and let them sort out the details. Researchers can also sign up for Otlet’s primary service, which is sharing biological samples between scientists around the world. “We created Otlet after hearing from many of our colleagues that they often have leftover samples that never get used and end up being prematurely thrown out,” Green said. “Biological samples are essential for many research project; they unlock information about animals that we use to better understand, manage and conserve species and ecosystems. The time and expense spent collecting samples from wild animals is incredibly high, and we wanted to stop seeing samples wasted and research opportunities missed. Currently we have more than 20,000 samples ready for research from 311 different species of plants and animals.”

The Otlet team has been amazed at the positive response they’ve received so far. “That's an incredible feeling knowing that we can help students desperately in need of data to finish their studies and research projects,” Green told me. “The diversity of student projects and data is incredible: We have students working on the thermoecology of desert tortoises and others looking at textiles used in dressmaking; we have 10-year data sets from fisheries, and even an offer for a project on dragon phylogeny. Yes, dragon phylogeny is a real thing, tracking the evolution of dragons in art history!”

The biological scientists I spoke to for this story were thrilled about Otlet’s expansion into data set sharing and matchmaking with students in need, while urging flexibility from universities on some of the rules for graduate student research. “I think it’s a great idea—many of us have several data sets from projects that were abandoned or otherwise shelved prior to analysis and publication,” Kerstetter said. “However, use of them as thesis projects will need some caution. For example, because the students won’t have collected the data, thesis committees will need to be accommodating regarding sampling methods, which may occasionally be inconsistent. Perhaps a month was missed, maybe an environmental parameter wasn’t recorded. Similarly, we should all exhibit flexibility as faculty members to these sorts of projects. For example, if one of my master's degree students works up someone else’s data, I’m not going to insist on being the last author on the publication, which was traditionally reserved for the major advisor. We should all remember that the student graduating with a respectable product should be the goal, not traditional academic niceties. The goal for these Otlet-style projects should be to show—in a crisis atmosphere, no less—that the student is able to correctly analyze the data and present the results in the appropriate context. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good!”

For social scientists such as Dayer and her students, fieldwork often involves interviewing and surveying humans, and some of those data sets might not be as easily shared over Otlet for practical and ethical reasons. “I’m not sure how this particular platform will work for the conservation social sciences, but I certainly like the premise,” she said. “Traditionally, conservation social scientists have not made their data sets available. Although this situation is changing, there are likely many survey data sets, for example, that have only been partially analyzed.” In the meantime, Dayer has been working with other conservation social scientists to adapt to new methods such as phone interviews and online surveys, while holding regular online conference calls for colleagues to share strategies and lessons learned.

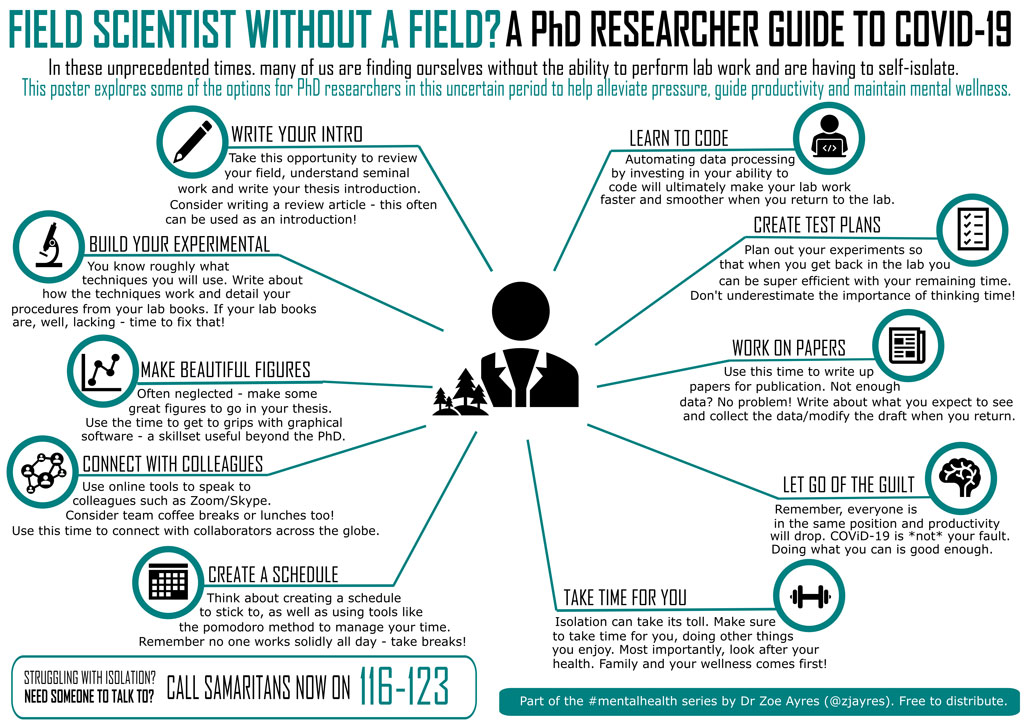

For those who can afford to miss a field season, Zoe Ayres, a visiting research fellow at the University of Warwick in England, has been creating and sharing a series of guides for what she terms “field scientists without a field” (see the infographic below). For those who’d like to be doing at least some work during all this craziness, things they can do without a field season include learning new programming or statistical skills, improving diagrams and figures, and writing introductions. They can also look for online presentation opportunities, as many conferences go online, to hone their speaking skills. “I created this guide to help scientists conceptualize what other activities they can still do to make the best use of their time, and alleviate some of the guilt and pressure around not being able to conduct a typical work day,” Ayres said. “This isn’t about productivity, it’s more about adapting to the new normal and finding new, creative ways to do our science. During this time, mental health, family, and friends have to come first. We can only do what we have the capacity to do, and that varies greatly depending on individual circumstances. Productivity is going to naturally take a hit and that’s OK—be kind to yourself!”

Other things that academics can do to support graduate students in these difficult times are more institutional than individual in nature. “One immediate, relatively simple solution would be to provide another year of salary for everyone on a current federal research grant,” Kerstetter said. “Those funded projects have already been pre-vetted for rigor and value. Good projects shouldn’t be left uncompleted when there’s a simple solution available. Knowing that additional salary support was coming would be a huge relief to many of the graduate students I know—the popular image of a starving graduate student is an accurate reflection of the reality that many are living on the economic edge of poverty.”

Although data collection is a major problem in a challenging time, everyone I spoke to was optimistic that a solution could be found. Says Dayer: “It’s been uplifting to see folks share their concerns, learn creative approaches, and realize we’re all in this together.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.