The Decline of Oregon's Rare Sand Dune Lakes

By Douglas Larson

As this lake system became popular for real estate and recreation, one scientist documented how its water quality and overall ecology deteriorated.

As this lake system became popular for real estate and recreation, one scientist documented how its water quality and overall ecology deteriorated.

In 1969, shortly after I completed a year of graduate research in limnology on one of Oregon’s coastal sand dune lakes, named Woahink, I decided to obtain aerial photos of the lake and the nearby majestic dunes that blocked the lake’s former short drainage to the sea.

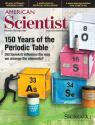

The photos revealed a sizable land-clearing operation on a large peninsula stretching out from the lake’s north end (see the left photo, below). Although from my boat I periodically had noticed the work, I never realized how extensive and environmentally destructive it was until I saw it from the air. Indeed, the forest on the peninsula had been clear-cut entirely, and bulldozers had scraped off much of the remaining vegetation and topsoil—all the way to the water’s edge.

Image on left courtesy of the author; Image on right, from Google Earth.

The project, completed by the Oregon State Highway Department, was one of several under development to accommodate a sharp, steady increase in post–World War II tourism and recreation along the Oregon coast. This development was eventually paved to create a parking lot, boat-launch, and visitor center, all of which replaced preexisting wildlife habitat and trees that had sheltered part of the lake’s north shore for a hundred years or more. Besides giving shelter, the trees formed a barrier that prevented precipitation run-off from washing sediment into the lake. Sediment, including organic debris, could promote nuisance growths of algae and reduce water clarity. I had little doubt that the project would impose those and other adverse effects on the lake’s water quality and ecological integrity.

I was concerned that other sand dune lakes in the area might also be threatened by human activities. Responding to my concerns, I proceeded to independently photograph the lakes primarily from an aircraft but also on the ground, compiling nearly 1,200 photos between 1969 and 2009 using a 35-millimeter Zeiss-Ikon Contaflex camera. For ground-truthing, aerial surveillance was coupled with occasional limnological surveys of selected lakes. This work provided an unusually long photo-historic record of lake changes. I hoped to demonstrate possible long-term deterioration of the dune-lake complex, a process that would probably be imperceptible in the short term but would be readily apparent over a generation.

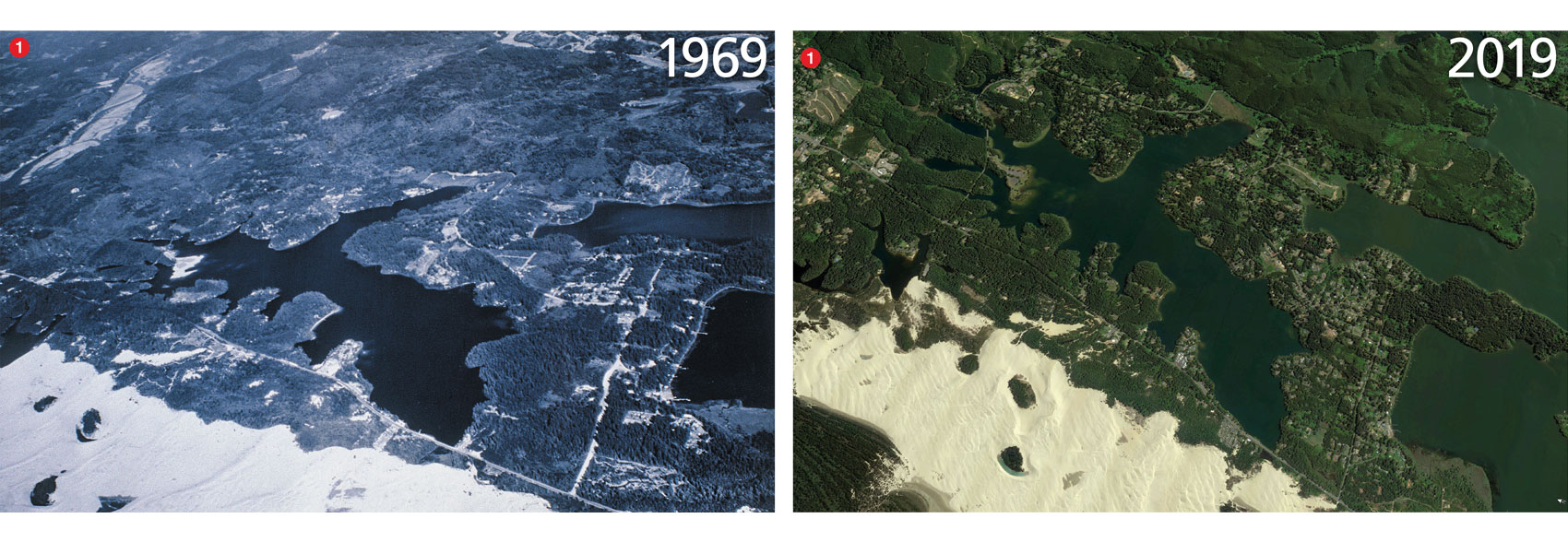

Approximately 40 freshwater lakes are distributed in a chainlike pattern that winds among prominent sand dunes along the central Oregon coast, stretching roughly 90 kilometers between Heceta Head to the north and Cape Arago to the south. The late ecologist W. S. Cooper designated this region as the Coos Bay Dune Sheet, which abuts the foothill slopes of the Oregon Coast Range and is breached by two major rivers, the Siuslaw and the Umpqua. Most of the lakes are sand-barrage types created by a post-glacial rise in sea level that flooded coastal river valleys whose openings to the sea were subsequently blocked by the inshore migration of ocean sands. Some dunes rise steeply to as much as 20–25 meters above the lakes’ surface elevations.

This lake assemblage may be unique along the West Coast of the United States and possibly to North America. This claim is based on Cooper’s description of the Coos Bay Dune Sheet, which he called “the most continuous and widest of the dune areas,” saying that it “furnishes the most comprehensive display of forms and processes.” In 1972, apparently convinced that Oregon’s coastal dunes were unique, the U.S. Congress designated a portion as the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area. Although most of the dune lakes are included in the national recreation area, a dozen or so are outside it, and these dune lakes are where some harmful land use occurs. Moreover, the national recreation area lakes are not fully protected. They, too, are affected, sometimes adversely, by vast numbers of people seeking recreation.

© OpenStreetMap contributors

Despite the coastal lakes’ early recreational popularity, surprisingly little was known when I started researching in 1969 about their limnological characteristics and other scientific features. My exhaustive literature search found only a few references, including one published as far back as 1897, written by B. W. Evermann and S. E. Meek. Most reports were prepared by the Oregon Game Commission and the Fish Commission of Oregon to determine the capacity of coastal lakes to produce and maintain fish populations for commercial and sport fisheries. Limnological data were sparse, and problems with water pollution, deforestation, the downslope movement of soil, and other human-related environmental impacts were not discussed. At the time, the importance of ecosystems was not yet appreciated—indeed the concept was not fully developed until Sir Arthur George Tansley defined it in 1935. It took several more decades and the environmental movement for the idea of ecosystems to begin to be appreciated in conservation policy.

But a few scientists were becoming increasingly aware of how human activities along the Oregon coast were affecting lakes, forest ecosystems, and ocean shorelines. S. N. Dicken, who studied Oregon coastal geology during the 1950s, argued that the effect of people on the Oregon coast had “upset the delicate equilibrium which existed under nature.” And, a 1938 report by Francis P. Griffiths and Elden D. Yeoman warned that coastal deforestation and the depletion of water for irrigation and power generation was causing “ecological changes” that were adversely affecting fish production. They identified Woahink Lake as one in which fish growth and production were poor due to a “lack of food.” Although this issue was seen as a fisheries problem, it nevertheless indicates that the lake at that time was generally in a pristine condition, as described below.

Woahink Lake resides in a steep-walled cryptodepression whose maximum depth of 21 meters extends almost 10 meters below mean sea level. The lake’s area is 3.2 square kilometers and its shoreline length is 22 kilometers. The lake is located outside of the national recreation area.

Limnological data for 1969 confirmed that the lake featured well-oxygenated, highly transparent, and chemically dilute waters that were largely free of nuisance aquatic plants, because of the lake’s low concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus. These variables define an oligotrophic lake. The undersupply of nitrogen and phosphorus, essential for biological growth and production, limits the abundance of lake biota, including zooplankton, small aquatic insects, and fish. Hence, although the lake exhibits clean, clear water and is in that sense pristine, its capacity for biological productivity is typically poor.

By 2005, Woahink Lake began to produce large, unprecedented algal blooms.

If Griffiths and Yeoman had obtained a more complete set of limnological data, they too would have probably found the lake to be similarly oligotrophic, which would account for the limited growth and production of fish. What their report therefore suggests is that human impacts to the lake before 1969 were probably minimal and thus inconsequential regarding lake purity.

Since 1969, however, relentless human intervention has transformed the watershed considerably. In 1969, for example, approximately 150 summer cabins and permanent residences lined the shore. By 1979, the number of homes had increased to 200, all of which discharged domestic sewage into the lake via septic tanks and drain fields. Lane County’s Department of Health and Sanitation estimated then that about 50 percent of the homes’ septic tanks were failing, allowing substantial amounts of untreated sewage to enter the lake daily. By 2005, probably in response to sewage-derived nitrogen and phosphorus, the lake began to produce large, unprecedented algal blooms.

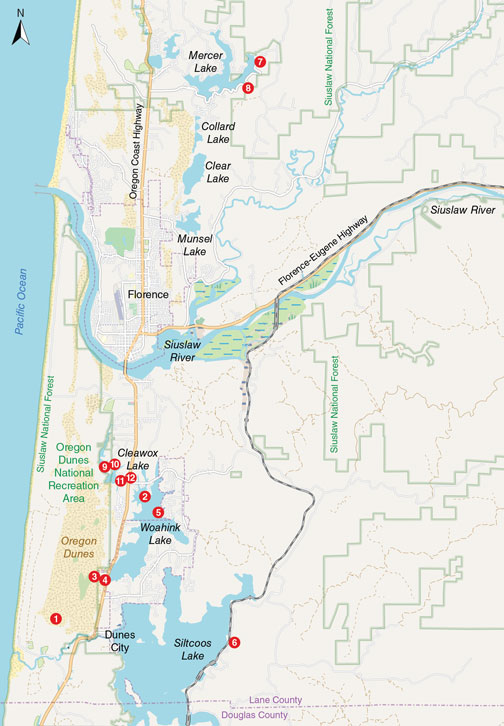

Images courtesy of the author.

In addition to septic pollution, basin soils are the source of other potential environmental problems. Because the soils are predominantly sand and sandy loam, they tend to erode and mass-waste considerably. This soil movement and loss occurs when lakeside lands are subjected to land-clearing, road-construction, and housing developments, resulting in unstable shorelines, submerged nearshore terraces, and lake sedimentation overall. At Woahink Lake and other coastal lakes, some residents have had to build retaining walls along their property shorelines to counteract erosive wave action and hold soils—and thus their homes—in place. Others have attempted to expand their lakefront property by excavating upland sand and depositing it offshore. These deposits of unconsolidated materials are eventually washed away by shoreline wave erosion.

Although recreation and tourism are worthy expressions of the American dream, they have also contributed to Woahink Lake’s degraded condition. Foremost among the various recreational opportunities in the lake’s watershed is Honeyman State Park. This facility, which adjoins the lake along its northwest shoreline, covers 19 square kilometers and is hugely popular, hosting 20 million visitors between 1969 and 2013. Nearby is the previously mentioned visitor center and boat launch that was installed on one of the lake’s north-end peninsulas during the 1960s (see above). For years, heavy winter rains (averaging more than 200 centimeters annually) regularly battered exposed areas, causing precipitation runoff to transport and deposit tons of soil and other debris into the lake. Erosive wave action scoured soils from the development’s shoreline, adding to the offshore soil deposit buildup that has contributed to observable shoaling in the open lake.

Images courtesy of the author.

Possibly as many as 2 million people visit the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area annually. This area is managed by the U.S. Forest Service for “the conservation of scenic, scientific, historic and other values contributing to public enjoyment.” It covers about 110 square kilometers and extends about 65 kilometers between the coastal towns of Coos Bay and Florence.

In the U.S. Forest Service’s 1972 inventory report, the agency wrote that the national recreation area’s dunes are “fragile and easily altered,” explaining that their “ecology is complex and can be turned, reversed, or even destroyed within one man’s lifetime.” Nevertheless, the national recreation area has been managed chiefly for recreation, which has imposed risks to the area’s “fragile and easily altered” ecology. During much of the year, dune buggies, all-terrain vehicles, jeeps, and motorcycles barrel across nearly half of the entire national recreation area, damaging ecologically crucial plants such as Port Orford cedar. They plow over dunes, scattering resting birds, some listed as threatened, such as the western snowy plover.

Image courtesy of the author.

Environmental damage in the National Recreation Area is readily apparent at Cleawox Lake. During the past 50 years, for example, hundreds of thousands of visitors have climbed the once-majestic dune along the lake’s south shore before descending the dune’s face, pushing sand into the lake and partially filling it. Once regarded as one of the world’s largest single dunes, it has since been flattened somewhat by the displacement of sand. As the dune has migrated lakeward, it has extended the lake’s shoreline about 125 meters beyond where it was in 1969. Sadly, no amount of restoration or reclamation will return this scenic wonder to its former grandeur.

As a newcomer to Oregon during the late 1960s, I was awestruck by the natural beauty of the state’s coastal region. Indeed, as the U.S. Congress declared in 1972, this extraordinary place was a “rare and beautiful gem.” Although most lakes appeared to be pristine or nearly so, conditions in their respective watersheds were not. At Woahink Lake, I observed along the shore and farther into the watershed numerous land-use activities that posed a threat to the lake’s oligotrophic condition. This state of affairs was generally the case at other coastal lakes that I subsequently visited.

My work and what it signified was virtually unknown among local citizens.

On completion of my work at Woahink Lake, I wondered about the fate of my research findings, now recorded in academic documents (such as my 1970 PhD thesis and a 1970 report for the Oregon State University’s Water Resources Research Institute). They were filed away where probably only a handful of people would read them or even know that they existed. Certainly, with few exceptions, my work and what it signified was virtually unknown among local citizens along the coast. Even those who resided on or near lake frontages were unaware. For them, knowing how their lakes’ watersheds were being managed and used, and how these processes could be environmentally damaging, was vitally important.

Galvanized by what I had learned at Woahink Lake, as well as the overall lack of citizen awareness regarding lake vulnerability, I decided to launch a program that would explain the purpose of my research and its relevance to the public. Additionally, I would emphasize the causal relationships between watershed usage and lake “health,” and explain the process by which lakes can decline from clear, well-oxygenated, oligotrophic bodies of water to eutrophic ones typically choked with weeds and filled with poor-quality water. Being self-funded and independent, I hoped that the public would consider me fair and unbiased even though I was championing an environmental cause.

Image courtesy of the author.

Adhering to the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words, I believed that aerial photos would tell my story far better than abstruse charts of limnological data, although such explanations could come later. My earliest photos were taken of Woahink Lake in 1969. Photography of other dune lakes began in 1973.

By 1978, I had enough photos and other information to begin taking my program on the road. The photos were often controversial, revealing the consequences of imprudent and exploitative real estate and recreational development. My first stop was a meeting with the Lane County Board of Commissioners in early 1978, where I presented a slideshow. Although most of the members expressed doubt about the photos’ authenticity, they approved a temporary moratorium on real estate development around lakes within the county’s jurisdiction. Unfortunately, the moratorium was short-lived because landowners who wanted to sell lakeside property threatened lawsuits over the matter.

Images courtesy of the author.

In 1990, a follow-up meeting with the same county commission again proved fruitless. Despite my recent photos clearly showing lake deterioration, the commissioners said that they “weren’t convinced the lakes [were] in trouble.” I was accused by one commissioner of being “against change and growth,” while another admitted in the local newspaper, The Register-Guard, that he “hadn’t figured out what we’re really losing.”

When it comes to lakes in peril, the outcry is hardly a bugle call to arms.

Throughout the program’s existence, 1969 to 2009, I often presented slideshows to various parties, including city councils, governmental agencies, citizens at town-hall meetings, and environmental organizations. During these presentations, disputes would sometimes erupt between those who favored real estate development and those who wanted it to halt. Also present were people who had a vested interest in decisions about the use and management of lakes and their watersheds. As workers in industries such as logging and wood products, tourism, recreation, and home construction, they were naturally not inclined to support a policy of restricted use of watersheds for the benefit of lakes.

Images courtesy of the author.

In the end, unfortunately my determined effort was mostly ignored. The logging of watersheds continues apace. Tourism on the Oregon coast is booming, apparently with little regard for its impact on lakes and watersheds. Research by scientists from Portland State University has reported that Woahink and other sand dune lakes have become increasingly eutrophic, with Woahink yielding extensive algal growths currently visible on Google Earth (http://earth.app.goo.gl/LNsSNi).

Nevertheless, I remain a strong advocate for lakes. In Oregon, individuals and organizations advocate publicly and vociferously for rivers, ocean beaches, Pacific salmon, old-growth forests, birds of practically every feather, clean air, reliable public transportation, safe drinking water, and even the rare red-legged tree frog, western toad, and clouded salamander. But when it comes to lakes in peril, the outcry is hardly a bugle call to arms. My monitoring program was intended to partially fill that gap, beginning with the rare and highly vulnerable sand dune lakes along the central Oregon coast.

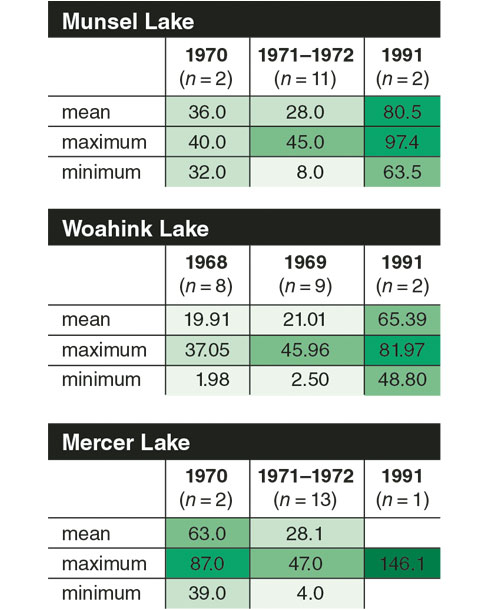

Data collected by D. W. Larson, R. C. Kavanaugh, and J. T. Salinas.

Contrary to popular opinion, a lake is not merely a geographical depression inhabited by fish and other aquatic organisms, and offering various recreational pursuits. Like a forest, a desert, or my grandfather’s cornfield in North Dakota, a lake is a complex ecosystem in which populations of organisms coexist in communities where life is a function of the nonliving environment. Because of its interwoven and mutually related components, a lake ecosystem is at risk when its watershed has been significantly altered by various human intrusions such as logging, real-estate development, recreation, waste disposal, and other destructive land and water uses. The resulting impacts can disrupt ecosystem stability and biological composition, possibly leading to irreversible lake degradation.

Between 1960 and 1963, Oregon’s automobile license plates were emblazoned with the motto “Pacific Wonderland.” That and other public-relations campaigns were efforts to not only invite tourists to Oregon, but also to encourage visitors who wanted to remain in the state as permanent residents. In the 1970s, as the state became increasingly crowded and developed, then Governor Tom McCall publicly issued a statement saying, “We want you to visit our state of excitement often. Come again and again. But for heaven’s sake, don’t move here to live.” That too was mostly ignored. Indeed, the state’s population has roughly doubled since then, now standing at about 5.5 million, all of whom seem to head to the Oregon coast on summer weekends and holidays.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.